Polygamy in the CAMPS

Earlier, I wrote on sexual and gender-based violence in the camps as well as the psychosocial support provided in the camps to Rohingya women in the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. According to aid workers and community leaders, most of the cases coming their way are related to gender-based violence—particularly domestic violence, abandonment, and polygamy.

During my time reporting in the camps, I have interviewed several women whose husbands abandoned them to marry again as well as women who had no idea where their husbands were in the camps (post-displacement).

While this is something you hear if you spend some time talking to people in the camps, somehow I was unable to expound the issue in words. I felt I was ill-equipped to write about a social practice such as this, which requires close knowledge of the Rohingya community’s culture and traditions as well as the impact of the humanitarian emergency on their lives.

While frontline aid workers and locals, who regularly interact with the refugees, are aware—the issue of polygamy and abandonment making its way into numerous reports from the ‘field’, it didn’t seem to be a wide concern otherwise. I, too, thought this was more of an arena for academic research, I thought, rather than a young reporter’s.

In an international conference on the Rohingya crisis held at North South University last week, a research paper presented on polygyny in the camps caught my eye. Among a glut of research work on matters relating to the Rohingya, this I thought was something that was under-explored and worth bringing up to a wider audience.

Researchers Md Rashedul Alam and Nayeem Sobhan, who presented the paper, too felt that the matter of polygamy (or polygyny), which has enormous implications for Rohingya women, was of utmost importance for the social condition of the camps. “They [Rohingya women] are already victimised, how much more victimised will they be?” says Sobhan.

Both work at an international UN agency and have worked on the frontlines of the crisis—their interest in the issue arose from what they saw around them in the camps every day and led them to undertake this independent research.

“We are in a Muslim country now, it is high time to take the opportunities of getting multiple wives.”

This quote was one of several the researchers presented from the male Rohingya refugees they interviewed in two camps in Ukhiya and Teknaf. Another was about how women no longer listened to them, and getting married again would “teach them a lesson”. While these uniformly paint the men as chauvinists, there are other factors to consider in this complex social dynamic.

Many researchers and aid organsiations have theorised rising polygamy in the camps to be the result of the trials the refugee community has faced—the scarcity of men, the lack of economic opportunities—the latter, for example, meant parents unable to feed many mouths were compelled to marry off their girls early or simply wanting to secure their daughters’ future in they trying situation they now found themselves in.

Earlier, too, aid workers and community leaders would say that Rohingya men were marrying again in order to get double rations. Now, with aid agencies registering women too, say Alam and Sobhan, there is less scope now to get double rations. This, it is important to note, is part of aid agencies’ and government efforts to empower women economically and socially, which also goes toward addressing the impact of gender-based violence on Rohingya women.

After moving into the camps, many Rohingya women reported to the authorities that their husbands had abandoned them or ‘disappeared’. Aid workers and camp officials, tracking the former men, would find some of these men living in other camps, having married another women and started a family there.

In a refugee camp where life is treated as temporary, lasting institutions such as marriages, births and deaths seem to hold less value than it does outside. Marriages were unofficial, until quite recently when the refugee, the relief relief and repatriation commission (RRRC) developed a marriage registration form—this however, is still not widely used.

It is difficult to estimate how prevalent the practice of polygamy is as marriages are not officially recorded, but aid workers and government officials in charge at the camps cite it as one of the major issues they handle in the camps.

Another widely cited reason for polygamy, is that here in the camps, Rohingya men no longer face the restrictions imposed on them back in Rakhine state. The Rohingya have long alleged that they would be asked for large sums of money (as high as 100,000 kyat, according to a 2014 report on discriminatory policies against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar by the human rights organisation Fortify Rights) and it has been documented that the Rohingya were forced to comply with many additional requirements before getting married, including appearing before law enforcement multiple times and waiting months and up to years, for approval.

Researchers Alam and Sobhan too found these and more reasons for the practice of polygamy—including the lack of work opportunities and idle time, and Rohingya men asserting their right to marry than once as a Muslim.

Another factor is that polygamy is not simply rising in the camps but in the locality as well. While intermarriage between the refugees and local Bangladeshis has been seen from the outset of the refugee influx, with local men in particular marrying Rohingya girls and women, these researchers say they also encountered cases where Rohingya men married local women.

This is extreme, claim the researchers, to the extent that quite a number of local men in the areas where the camps are situated, have unofficial ‘second’ or ‘third’ wives. This was seen in both the case of well-off men as well as less financially solvent men who married Rohingya girls from comparatively financially solvent families.

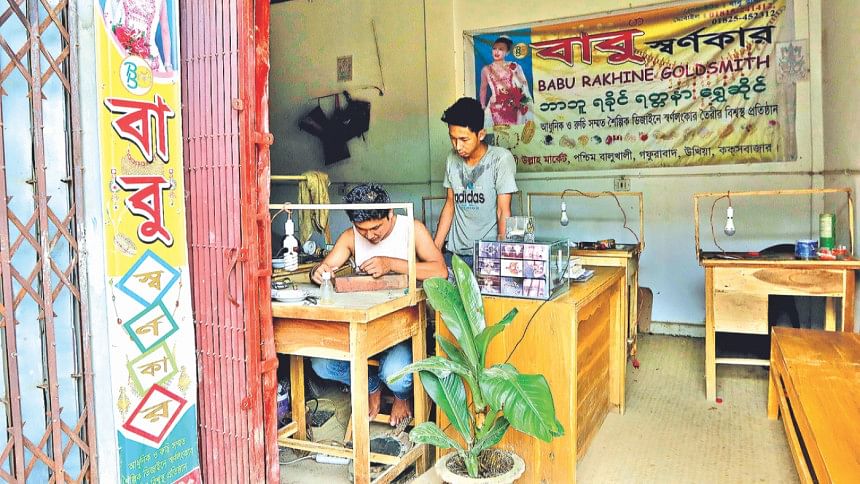

Some families, while fleeing their homes in Rakhine, have managed to bring along some assets—most significantly, gold. Gold and jewellery markets as well as shops selling wedding clothes flourish in and around the camps.

Even prior to the influxes, locals would tell us that these marriages were common across the shared border, because Rohingya girls were “beautiful”.

Technically, marriage between Bangladeshis and Rohingya is illegal, following a 2014 law that forbids registrars from officiating these. In January last year, the ban was upheld—the government cited that intermarriage was being used a means of getting citizenship. The sentence is up to seven years in prison—but enforcement is difficult.

A small snippet of the dynamics surrounding the factors causing and resulting from polygamy in the camps, it shows a need for further research into the matter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments