A reminder that trees are alive

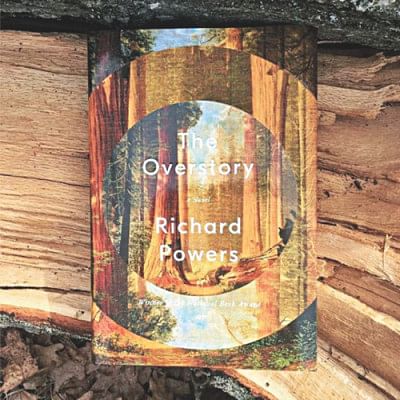

To call it ‘climate fiction’ would barely scratch the surface of what it really is. Richard Powers’ The Overstory—winner of this year’s Pulitzer Prize for Fiction—is an exhilarating glimpse into the majesty of plant life, and a humbling reminder of the fact that we humans aren’t the central characters in the story of this planet.

The novel is peopled by nine characters—all strangers—situated across America, all of whom are in one way or another impacted by trees. In Brooklyn, the Norwegian Hoel family grows and thrives, as does the chestnut tree it documents in its backyard for generations. In Wheaton, Illinois, Mimi Ma inherits her father’s undying affection for the mulberry. Five-year-old Adam Appich discerns the temperaments of elm, ash, ironwood, and maple (straight, droopy, good, and red like each of his siblings), and grows up to study the behaviour of humans when removed from society as a scholar of psychology.

Unforeseen events force stenographer Dorothy Cazaly and property lawyer Ray Brinkman to reconsider “what conveys a right, and why should humans, alone on all the plant, have them?” Born an orphan, Douglas Pavlicek enlists in the U.S. Air Force during the Vietnam War and crashes into an ancient Thai banyan that saves his life. Child prodigy Neelay Mehta inherits his father’s love of coding; following a fall from a Spanish oak, he creates a forest-inspired video game that becomes a global phenomenon.

Impetuous college senior Olivia Vandergriff devotes her life to fighting deforestation after a fatal accident involving electrocution. And dendrologist Patricia Westerford, who grew up loving trees more than her fellow kin, makes a startling discovery about how they function as members of a community, sensing danger, sending signals, protecting each other via their roots. She has “glimpsed into this small but certain thing that evolution is up to,” she discovers. “Life is talking to itself, and she has listened in.”

These chapters all work as standalone stories on their own. At the end of each, you want to close the book and simply savour what you’ve just read. But framing and weaving them together is the science, history, and ethnography of trees in vivid, if slightly wordy, prose. Of the Old Tjikko, a Norway spruce known as the world’s oldest tree, Powers writes: “Above the ground, the tree is only a few hundred years old. But below, in the microbe-riddled soil, he reaches back nine thousand years or more.” He describes the infinite hospitality of a dead tree, supporting the ecosystem of countless invertebrates, and defines a forest, a “threatened creature” made of living things joined by air and the underground, a creature “that has intention.” From a football field’s height above ground, sitting atop a centuries-old redwood with two of the main characters, you notice that the humans are but the ‘understory’ in this novel. You realise that you’ve spent just long enough all your life rooting for people in books. Here, the real protagonists are the trees—”the most wondrous products of four billion years of life [...] [which] go down in twenty minutes and are bucked within another hour.”

The structure brings to mind Jane Alison’s essay “Beyond the Narrative Arc” published in The Paris Review earlier this year, in which she pointed out how a story can take a shape other than the typically linear causal arc. “The arc makes sense for tragedy [as Aristotle first spoke of it in Poetics], but fiction can be wildly other,” she wrote. It can replicate the shapes of a meander, like a river, an explosion, like radiating sunlight, or a swirl, like the rings of a tree. The Overstory follows the pattern of the latter. Like the loops marking the inside of a trunk, the nine stories mingle and proceed concentrically. In a refreshing reading experience, you observe from above—the way you would calculate a tree’s age by counting its rings—as the characters evolve, struggle, and come in contact in surprising ways to arrive at the issue of deforestation at the novel’s heart. The plot may borrow the (real life) setting of the ‘Redwood Summer’ of 1990, during which guerrilla activists protested the logging of ancient sequoias in California, but the discussions it rouses are relevant and particularly urgent today.

But it isn’t just about rooting for trees. Powers has always been fascinated with the mechanisms of nature—his National Book Award winning The Echo Maker (2006) explored the themes of identity and consciousness, but it was also about the “strange intelligence of birds and [...] forgotten kinship with creatures,” he told the LA Review of Books. In The Overstory, his 12th novel, Powers seeks to underline how interconnected all the parts of nature can be, humanity included. If his characters, in one instance, find their lives changed by trees, in another they reprogramme those very lives to fight for them. The relationship feels unforced and nuanced, as the people travel between indifference, awe, gratitude, and fierce loyalty towards those green beings. Powers’ language reflects this connection. The human lives pass in seasons, in “wood years” and “the length of several owl calls”; the people “bloom like something southern facing.” Like the forests it tries to describe, the prose bursts with enough colour and wildness that the occasional wordiness and redundant sentence reasonably resists pruning. The result is a book that holds your interest through over 500 pages of focus steered away from humanity.

At several points in the book, the fight against deforestation turns brutal. Protesters remain shackled together for hours, forced to urinate amidst the huddle. They lose their jobs, have their genitals pepper-sprayed and their eyes smeared with pepper paste by the police. The scenes, devoid of sugar coating, highlight how defending the environment isn’t always a rosy picture. And yet the novel is swept by optimism, drawing on a single idea that has long allowed people to “reach down [themselves]” and “do one small thing that seems beyond them”. One hopes that a novel that accomplishes so much else can also inspire its readers to do more, act more for their planet based on this one word. The word is ‘nevertheless’.

The writer can be reached at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments