A Sense of Smallness

“The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today”

– Engraved on the Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument

Forest Park, Illinois, USA

There are few things more difficult in life than a full awareness of the conditions of one’s possibility. To come to terms with how little of my world is my own creation, and just how much of it is the accumulated labour of dead generations and living masses far removed from my consciousness, is to grapple with a sense of smallness and insignificance. It makes living in an age of hyper-individualism and entitlement a constant struggle. How is it that I have clean clothes to wear today? How did this plate of food in front of me get here? How is there thisroad that takes me from my home to my workplace? How is it that the bathrooms here are clean, when they were anything but when last I left? Who opened the doors in the morning and turned on the lights? How is there a building here in the first place? How is it that I am able to write in this way? Where will my next meal come from? What will I do if it doesn’t? Why do I not need to worry?

Questions such as these lead inexorably to an inconvenient truth—our worlds are not our own. Very little of who we are, what we do, and what we can do, can be attributed to our actions. If human beings are defined by the act of consciously producing our lives and means of living through work, as the young Marx and Engels put it back in the mid-1840s (in The German Ideology), then any structural and sustained division of that work (i.e. the ‘division of labour’) produces a partial consciousness of how our world is produced and reproduced. We are never fully aware of how much the Other’s sweat and blood makes our lives possible—the other race, the other gender, the other class, and countless other Others. While such a partial blindness is as old as social hierarchies are ancient, since the 17th and 18th centuries it has been nurtured and fed by a discourse that did not exist before, and which since the 1980s has reigned more or less unchallenged in our private and public imaginations.

The idiom of the ‘agentive individual’ has always been fundamental to the cosmology of liberal modernity, occupying the same status in social thought that the atom has long occupied in natural science. The concept of individual agency infects our academic, professional and folk knowledge about how society works. It fundamentally prefigures the kind of reality we can see or dream of. It lies, I believe, at the heart of the extraordinary reverence with which we treat ‘the market,’ which to us has become an infallible, non-human/‘natural’ subject that orders our post-Hobbesian world caught in a permanent state of war. The market and the agentive individual are two sides of the same coin; just as religion was for Émile Durkheim ‘society’ worshipping itself through projection and misrecognition, ‘the market’ is the modern agentive individual worshipping itself. This is why it has become almost impossible for us to conceptualise all human productive activity as fundamentally social, and to see through the illusion of individual effort separate from our surrounding complex networks and the wealth of capital , accumulated through the ages, from which we draw every day.

It is our inability to account for the combined labour of others, labour that makes our lives possible, that fuels our comfort with obscene displays of wealth, and our discomfort with working class demands for a higher minimum wage and shorter work hours. It reduces our understanding of the modern world into one where there are only so many kinds of constraints on agency (the physical/natural, the technical, and the legal), making forms of social, inertial and other kinds of power invisible and unintelligible. The idiom of individual agency can also be seen in our complete identification of ‘democracy’ with ‘elections,’ to the extent that the two have come to mean effectively the same thing. Thus, when democracies are ‘ranked’ by international organisations and political scientists, ‘free and fair elections’ dominate all other criteria. Modern day elections resemble little more than an array of choices of television channels—all that matters is the ability to choose. Even when collective action is acknowledged, it is rarely understood as anything more than an additive product of individual agency. The idea that political agency might actually originate in the collective is completely unintelligible to the modern liberal subject.

So what has any of this to do with May 1? An awareness of the need for collective action has been at the heart of popular egalitarian movements as far as back as historical record can take us. But it was particularly in 17th century England, amidst a vicious Civil War, that traditions of collective action fused with a new counter-hegemonic discourse of history and power to produce a proto-socialist politics. Amongst them were the Levellers, who agitated for political equality, religious tolerance and popular sovereignty, and the Diggers, who proclaimed the injustice of the enclosures of ancient common land (a development responsible for creating mass landlessness and destitution, directly contributing to the birth of a property-less working class) and their right to occupy the commons once more. By the next century, socialist politics of various forms could be found all over Europe and America, enabling and learning from the wave of bourgeois-liberal revolutions fundamentally changing the political landscape. The Labour Movement as we know it was born with the Chartists in 1838, with growing recognition of what would one day come to be articulated as the fundamental contradiction between social labour and private accumulation. In September 1864 a relatively unknown German refugee journalist by the name of Karl Marx was invited to a London meeting of Chartists, Owenites, Blanquists, Proudhonists, socialists, nationalists and republicans from all over Europe, forming the International Workingmen’s Association, to be known to posterity as the First International, boasting as many as 8 million members at its peak. In 1871, the legendary Paris Commune became the first living example of that elusive utopia, ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat,’ that has inspired and haunted millions for so many years. By the turn of the century, the so-called ‘specter’ of Communism was not so much a specter as a colossal hammer threatening to smash Europe and make it anew, and at the heart of it all was the Labour Movement. As the Industrial Revolution tore apart land, life and the past, the newly born working class created its own vehicle of defense and attack—the trade union.

The union allowed the anonymous worker, one among millions, threatened with poverty, joblessness, arrest, torture, and death (by nature and the State), a way to become more than they were alone. They fought for everything, including much that we today take for granted. We commemorate May 1 as the International Worker’s Day (or Labour Day) because on this day in 1886, more than 300,000 workers from across the United States went out in strike, with a group of anarchists leading 40,000 strong in Chicago, the heartland of the movement. The demand? The 8-hour workday, something that most people reading this have probably never thought of as something that had to be fought for. The general strike on May 1 was followed by a nation-wide wave of arrests, beatings, torture, and deaths. On May 4 a peaceful demonstration was taking place in Haymarket Square to protest the killings, when the police marched towards the speakers to disperse the crowd, a bomb was thrown towards the police by agents unknown, and the police responded with indiscriminate firing into the crowd, killing civilians and police alike. Eight anarchist activists (most of whom were not even present on the day) were arrested, convicted and ‘tried.’ One year later, four of the arrested were hung, one took his own life the night before his scheduled hanging, and the image of the anarchist as a bomb-throwing chaos-monger was propagated throughout the country, to become forever lodged in our imaginations.

Our blindness to the labour of others produces an almost childlike belief about how the world works. We see that workers in general are better paid, better treated, and have more rights in general in the so-called ‘developed’ world, and we assume that they just have more benevolent political leaders and a more ‘deserving’ citizenry (we have all cursed our fellow citizens as deserving of nothing but the worst in the world at some point or another), or even that such things happen ‘naturally’ once a country is ‘developed’ enough (this latter is responsible for the ‘freedom-is-a-luxury-good’ concept, which is extended to civil rights in general, gender equality, sexual freedom and reproductive rights, environmental protection etc.—everything can wait until after ‘development’). There is nothing ‘natural’ about any of this, however; nothing just happens. Every right and privilege that anyone living today enjoys was once fought for, probably for generations, and probably bought in blood. In the world of professional work, such rights were fought for (and are still being fought for) by trade unions and other workers’ associations. The right not to have to work up to 18 hours a day, the 5-day workweek, the right to a living wage, the right to have holidays and paid leave, the right to get sick sometimes and not have to work with serious debilitating illnesses, children’s right not to become stunted by strenuous labour during their formative years, the right to have enough time to eat lunch and go to the toilet, the right to not be terminated without notice and compensation, the right to maternity leave, the right to safety at the workplace and compensation in case of accidents, the right to bargain for higher wages without fear of termination. None of these rights, wherever they exist, ever just appear; they exist because they were fought for. We misunderstand the nature and necessity of unions because we continue to misunderstand where these things we take for granted come from, and because we naturalise the market just like we naturalise such rights.

The ‘laws’ of demand and supply that those threatened by the Labour Movement love to deploy as weapons are not transcendent or immutable; they are patterns that emerge through the actions and interactions of human beings in the marketplace and beyond. There is nothing ‘natural’ or inherently fair about any market price, including the price of labour-power. Every price is a product of bargaining, of haggling, no matter how many people are involved. The formal equality of the law does not make all equal players in such haggling, nor does the fact that all parties by definition gain from voluntary market exchange mean that their gains are somehow equivalent. When I pay a rickshaw-wala for a ride, the fact that the latter benefits as well does not change the fact that only for one of us is this a choice between strenuous and cheap physical labour on the one hand, and chronic poverty and starvation on the other.

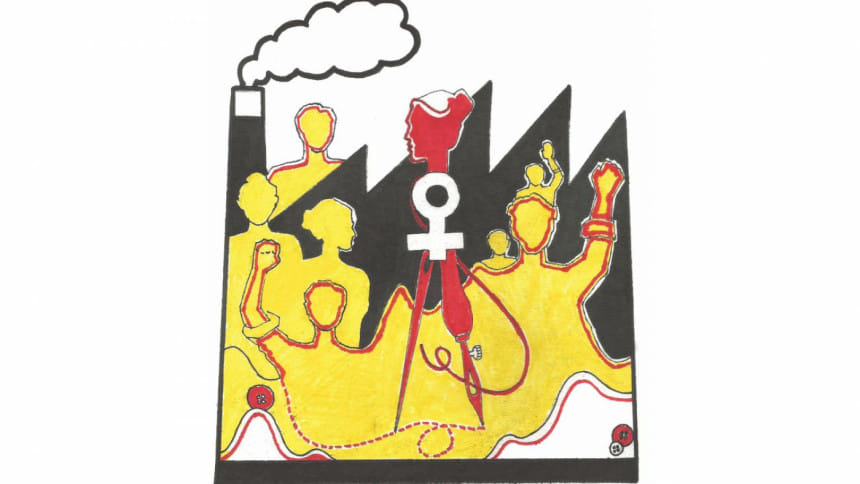

Wage-labourers, facedwith extraordinary wealth and political influence, have no choice but to join together and even the playing field a little. And why not? After all, we do not begrudge factory owners from doing the same thing in order to boost their bargaining power; in fact, we are so fond of owner-associations that we frequently elect their leaders to public office. Unions have historically been the most important (and often the only) wall between inhumane work and the precarity of unemployment; without unionisation, workers’ welfare depends entirely on employers’ whims and fancies. Small wonder then that the Bangladeshi state, eager to maintain our status as the world’s factory for cheap and disposable clothing, has made every effort to stand in the way of effective unionisation. Where trade unions do exist, they are almost always either affiliated with the ruling party, led by workers who have struck deals with management, or follow an NGO model more focused on ‘training,’ ‘awareness’ and attracting foreign donors than radical political action. The millions of workers in our RMG industry need real trade unions, because so much of what the rest of us take for granted are yet to become rights for all. ‘Voluntary’ overtime that is somehow mandatory and off-the-books (and thus workdays that can extend well into the night, even as late as 10 pm or 12 am), sub-contracting to unnamed factories far beyond the purview of regulators and the law, sacrificing weekends to earn a few extra pennies, tolerating constant verbal and physical abuse, no paid leave, no sick leave, sexual harassment, inability to send their children to school, exorbitant pay-cuts for arriving five minutes late to work, unlawful and arbitrary termination, falling sick on the factory floor, dying on the factory floor, intimidation and termination at the slightest sign of dissent and political activity, photos and names plastered all over the region as a warning to other factories not to hire such ‘troublemakers,’ the so-called ‘Industrial Police’ ready to make mass arrests, ready to beat, torture and even kill workers who dare to exercise their right to assembly. Humanitarianism, charity and ‘corporate-social-responsibility’ cannot solve problems of power; only collective action can. We need unions, and not just in the factories. In our schools and universities, in our banks and corporate offices, unions can make the difference between prosperity and precarity.

Nothing is free, and nothing just happens. From Haymarket to the Rana Plaza massacre (NOT ‘accident’) of 2013, the history of Labour is written in blood. We had to lose over a thousand lives before basic health and safety regulations could become institutionalised in Bangladesh, and that too at the behest of foreign donors and agencies, not those who claim the right to represent our country’s citizens in parliament and the world. Every single paltry increase in the minimum wage has come in the aftermath of protracted, bloody struggles, struggles that leave workers and activists broken and battered. Part of the problem, however, is that the spectacle distracts us from the everyday violence that is much harder to seethe shortened lifespans, untreated ailments of the mind and body. So many have been lost, and so many are always on the brink of being lost, not just to state apparatuses and reactionary forces, but to our own parties and programs, and our own negligence. On Wednesday, April 24, exactly six years after one of history’s bloodiest mass murders, labour activist and Rana Plaza rescue worker Nawshad Hossain Himu set himself on fire outside his Ashulia home. He was only 28, and as one of his comrades recounts, far too young to have seen, heard, smelt and breathed what he did in those ruins. It would behoove us not to treat his death merely as a release from an unbearable trauma, nor a fiery rejection of an indifferent world, but also as a reminder to all of us who write articles like this and read articles like this, not to forget that collectives are still made up of flesh and blood, body and soul.

The world will always look away. We cannot. After all, we are so small, and so few.

Comments