A story untold

I was born in Nabinagar thana, Brahmanbaria district (the then Comilla district). My ancestors were not involved in any kind of job or business. At one point, our insolvency reached a point where it was no longer possible for me to continue my education, so I moved to Dhaka to earn a living. During that time, my brother used to work at a jute mill. My initial plan was to join the mill, but the authorities rejected me as I was too young. However, after a few years of roaming around the city, in 1963, I got the opportunity to work at the Bawani Jute mill as a substitute worker.

During the early 60s, Maulana Bhashani was at the forefront of our politics. Among the youngsters, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Muzzaffar Ahmed played a prominent role in politics. The political space was shrunk due to the oppression on political leaders by the dictatorial regime of Ayub Khan. Amid this political lull, workers came out as a strong force to challenge the martial law administration in East Pakistan. In 1963, a strike took place at the spinning mill of East Pakistan. It was led by Haider Akbar Khan Rono, Kazi Zafar and others. They were joined by workers from mills in Dhakeshwari, resulting in an even bigger strike for 43 days with the shutdown of 30 factories. This was a significant event, as prior to this political parties hadn’t been able to bolster a massive movement against military rule. This was the first time I witnessed such a powerful strike.

In January 1964, communal violence broke out among the workers. The workers of Demra, Adamjee and Narsingdi were provoked by the coterie of 22 families of Pakistan and engaged in conflict without understanding the context. Workers from minority communities were mercilessly killed during this riot. The politically conscious group of workers, most of them being from the minority community, faced a severe setback.

However, the workers, rising above the internal difference, successfully called a strike on July 1, 1964 for the demand of Rs 125. This strike was led by the pro-Muslim League Labour Federation. Many leftist leaders were involved in this labour organisation. However, the leaders of the strike called off the programme after they were arrested. But the workers did not agree to this, and they prolonged the strike for 21 days in five mills in Dhaka with the participation of 40,000 workers. A temporary agreement was reached with the promise of an 8.5 percent salary increase within three months. The agreement was not implemented, and as a result, another strike was called in October.

Meanwhile, a riot broke out between workers from Noakhali and Barishal in Khulna industrial area on July 1, causing significant damages to the workers. The entire Khalishpur was set on fire. Muslim League leader Sabur Khan sent the workers of Noakhali, Dhaka and Comilla to Chandpur in five launches. For this reason, the worker’s strike in Khulna could not be sustained.

In October that year another strike resumed in Dhaka and the adjacent area, and it continued for 56 days. The strike was supported by the political parties of East Pakistan. A combined front was formed with the participation of leftist and reformist labour activists. After 56 days, an agreement was signed which made the 22 families surrender and bonuses were introduced. The minimum wage stood at Rs 61, the same wage that the Indian labourers received at that time. In fact, the currency value of East Pakistan was a little higher than that of India. It showed that the workers living here were advanced in terms of payment than workers in the neighbouring country. Needless to say, this strike successfully brought the workers into mainstream politics. The workers earned the trust of the people by making them believe that it was possible to fight against the Ayub Khan government. Ironically, the contribution of workers and labourers to our politics remains neglected in our mainstream history texts.

In 1965, the Indo-Pakistan war took place. Surprisingly, the communist leader Bhashani supported Ayub Khan at this time, which affected his image. After the war, a roundtable was held in Karachi among the political parties, where Sheikh Mujibur Rahman placed his famous Six-point plan.

After the end of the war, Ayub Khan released four important communist leaders. They stood against the Six-point demands. A division emerged in secret communist party and the communist movement divided into two streams: Pro-Peking and Pro-Moscow. It was a major setback for the labour movement because leftist organisations had a stronghold over both the labour and peasant forces.

During the tumultuous period of 1969, workers again played a key role in fighting the autocratic regime. Workers realised that their participation was instrumental to run the movement. I already got the membership of the secret communist party during this time. The party urged us to involve workers and labourers in the movement. Awami League, particularly Sirajul Alam Khan using his connections in jute mill areas in Naryanganj, also urged workers to join the uprising.

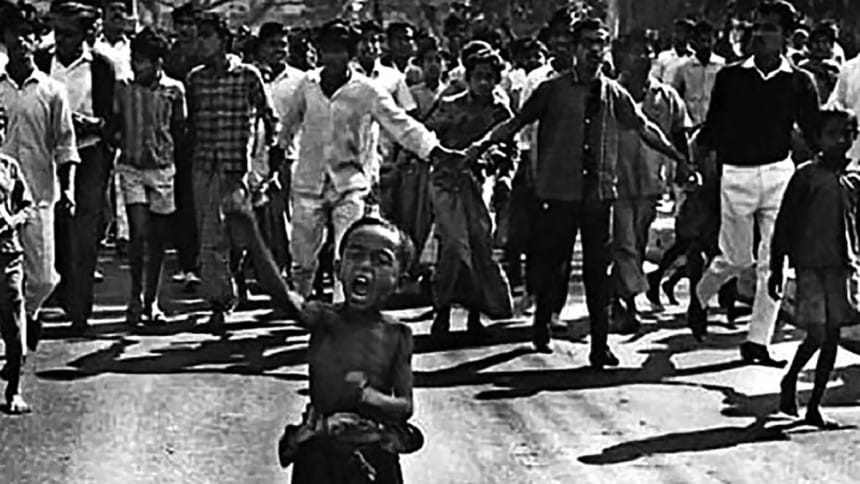

We, the labour leaders from different ideological leanings, came to a collective decision to take the workers to the street in protest of the killing of student leader Asad. As decided, on January 24, 1969 almost 40,000 workers started a rally from Adamjee at 7am. Workers from surrounding mills and common people enthusiastically joined the procession. By the time the rally reached Tikatoli, the number of protestors went beyond 1 lakh. The west wall of the Secretariat was demolished once the protest reached Paltan. Even the employees in that area joined us, leaving their regular office work. This massive movement led to the mass uprising of 1969 which eventually lead to the downfall of the decade-long military dictatorship of Ayub Khan. It was a glorious achievement. Unfortunately, the whole credit was usurped by some political leaders.

The Agartala conspiracy case was still not waived after the mass uprising. Workers actively participated in freeing Bangabandhu from the false case. The laborers used to work in the mills with the slogan—“We will break the locks of the prison and bring Sheikh Mujib out” (Jail er tala bhanghbo, Sheikh Mujib ke anbo).

During the Yahya regime, a student protest was held in West Pakistan demanding autonomy and democracy. The protest implicitly inspired the Bengalis to stage a demonstration against military rule. After 10 days of protest, the workers surrounded the mills and factories, shutting down all regular activities.

In the wake of another labour movement, the administration of Yahya Khan was compelled to adopt two policies under the commission of Nur Khan. The first one was concerned with the increase of minimum wage and the second one dealt with the initiation of labour law. The agreement came into execution, and the minimum wage became Tk 125, whereas the minimum wage in Karachi was Tk 140. However, Tk 125 was enough for a worker to lead a decent life. During that time, implementation of ILO convention was more effective than now.

During the Liberation War, the workers went back to the village and encouraged the people to take up arms to liberate the motherland. Bangabandhu acknowledged the contribution of the workers, thus adopting policies to protect the rights of the workers. Unfortunately, he couldn’t finish his job.

It is a matter of sorrow that independence couldn’t bring liberation for the toiling masses. The labour law and minimum wage gradually deteriorated since independence. The labourers and workers apparently lost their rights in independent Bangladesh!

As told to Ananta Yusuf, The Daily Star. Translated by Labiba Faiz Bari, contributor to The Daily Star.

Comments