THE HOUSE OF MAD

The child came just as dawn was about to crack. The earth had almost completed one rotation and was getting ready to light up again and along she came as the darkest hour of the night came to an end. She brought with her good luck and her family heirloom held firmly in her hands. The good luck she delivered to her father, who had just returned from a war in the Middle East to welcome her into the world. She was named Nauroze.

Minu held the child in her bony arms and wondered what the future held for this daughter of hers. She had come after many prayers, many sacrifices and many medical treatments. Minu had even sat through a snake charmer’s magic chant and a circle of snakes for Nauroze.

And once she came, she brought along a chance at freedom for Minu. Nauroze would get an education, grow up to be self-sufficient, be free to go wherever she wanted. She would not suffer the same way as her Ma. She would not get married off to a stranger because her father suddenly decided her destiny one fine day.

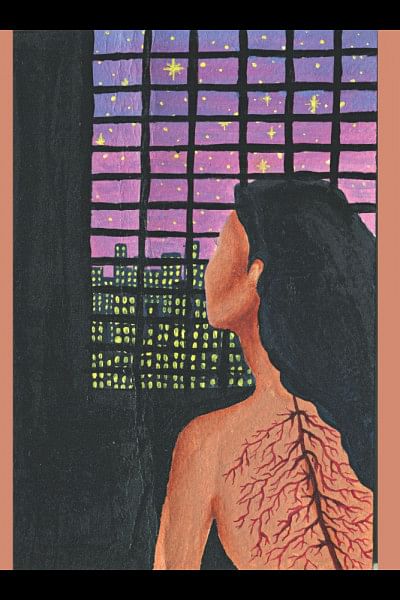

Mother and daughter did not know it then but they were fated to be caged. Freedom would be fleeting for them, trampled by Shafiq’s rage, by the lack of money and education, and the heirloom carrying madness and magic that had arrived with Nauroze.

***

After nearly four years of living in the village by the wispy-green round hills, the two would take the train to Dhaka and eventually board a flight to the Middle-east to meet Shafiq, Nauroze’s father.

It was their first time travelling any farther than the vicinity of the village and the main town square. On the first days of September mother and daughter boarded the plane. What a wondrous affair for both pairs of eyes. None of them had seen anything of such huge proportions. It appeared like a metallic bird. Minu and Nauroze watched in awe and took in the strange technology of chairs reclining up and down, people hurrying through the aisles with trays full of hot buns, coffee, small packets of Lurpak butter and fruit jam.

Nauroze felt sudden pangs of fear. She was leaving everything familiar in her life—her grandmother, her cousin brother with whom she played endless hours of hide-and-seek using the old mango tree as a hiding spot, the huge sprawling house that is her dadubari and everything that was known and so dear, all to take a leap into the vast unknown with her young mother.

The journey did not take long. Those first few moments after they landed in the new country was surreal.

They tugged at their luggage and tried to make it down the stairs as Minu refused to take the “moving stairs” at any cost. Shafiq was late, and this upset Minu, but she refused to express it once he did show up.

Nauroze remembers her father being unabashed and unapologetic for leaving his daughter and wife standing in the desert heat, completely stranded in a new country.

He piled their luggage into the trunk of the humble 1980 red Toyota Corolla before zooming them away from the airport. Shafiq was an immigrant in this nation, but not a seasoned one like most of their neighbours would be. Shafiq came here after his father’s death to try and support his family in Bangladesh. He started out as a carpenter at a factory.

It was a good thing, because he had always had a way with his hands, designing and carving out tiny mementos. He worked up the ladder very quickly, slowly starting to mingle with the top business people of the country, getting better and better at his work.

By the time his wife and daughter arrived, he could already afford a nice apartment in a small residential block full of other immigrant families, mostly from South India and Sri Lanka. It allowed his family to associate with the kind of people they would otherwise have very little reason to befriend.

Minu and Nauroze found it hard to settle down at first. Both of them were bitterly lonely, in a new country where neither child nor mother understood the language, the currency, the roads or the food.

Still, like all other immigrants, they persisted. Over time, even thrived. They managed to co-exist with other immigrants, most of whom were either academics with well-paying jobs at different schools, or nurses, doctors and engineers. It was only Nauroze’s family that did not truly fit into the social circle they were pretending to be a part of.

Nauroze was admitted to a school in her neighbourhood with the help of one of her father’s business partners, someone who understood English and penned a small application for the child, urging them to enroll her into the kindergarten in the middle of the school year.

On school days, her mother parted her hair in the middle in a very straight line and tied it up into two very tight braids. She packed her a lunch of ‘Bombay toast’ wrapped in the same polythene bag in which the bread came. Nauroze and two of her next-door neigbours from Bangalore and Kerala all piled up into her father’s car to be driven to school. She sat quietly, seat belt securing her tightly to the front seat, and stared outside trying to trace back the path to her home from school.

First a sharp right from her house. Two residential apartments on both sides, both sandstone coloured, then a supermarket (usually displaying a variety of Indian produce) and the Fuji Photo studio album, another stretch of a residential block and then onto the main road with the huge McDonalds outlet in the front and the sprawling supermarket named Jamiya. At least that is what her father called it. After the Jamiya, they crossed the large open market which smelled of incense, burning sandalwood and doner kababs in the evening. In the mornings, though, it was full of the lingering smells of last night’s hookah, coffee, sandalwood and the Islamic perfume. Right after the big market was a left turn, which brought them to an expansive desert landscape and there, at one end of the desert, were the maroon gates of her school.

The first week at school went by in tears. Nauroze planned constantly of escaping but for some reason, her teacher Gretta had locked up the room. She still found tiny ways to resist. She tore up colouring pages, screamed in her mother tongue and even tried to grab the teacher’s hand, but to no avail. She also distinctly remembered feeling shameful of her tiffin wrapped inside a polythene bag. The rest of the children brought the food in boxes and it made her ears burn.

A whole year passed before mother and daughter came to terms with a life among foreigners—and even managed to take some joy in it.

Minu found a friend and confidante in the old Bangladeshi lady her husband had hired to help around the house. Banu was like a grandmother to Nauroze and a mother and friend to Minu. Banu had lived in the country for nearly 20 years by then, working as a cleaner by day at a local school where all the Arab children attended.

She often bought left over pencil boxes, colourful books in the Arabic language, and even some food when she came over after work. Nauroze would wait with bated breath for Banu, because her arrival meant she would get to gorge on falafel and aubergine sandwiches and on the weekends, all go to the park a little distance from their home. Most days, they would hitch a ride with someone heading towards that direction.

Nauroze’s father was absent on most of these days. She would sometimes hear Baba heading out early in the morning and not return till late into the night. It was mostly her and her mom going about daily chores, watching hours of Animal Planet, Chip ‘n’ Dale, Talespin and Disney’s Adventures of the Gummi Bears. Her mother slowly started to lose her inhibitions and make friends. Vediya’s mother taught her how to make fish curry with coconut milk, coconut shavings and curry leaves. Rumpa’s mother, a nurse by profession, became her groceries partner, showing her from where to source fresh moringa sticks, new potatoes, jhenga, dhundol, potol and all the familiar vegetables that Minu was used to cooking with.

As they settled into their routine, Nauroze started to notice the strange unhappiness that would grip the house on certain days. Her father and mother would break into arguments over silly incidents that were blown out of proportion, thanks to her father’s erratic temper.

She remembers one particular incident, after her little sister was born, when Baba started to accuse her mother of stealing. Ma swore against it. But he kept on insisting, breaking her little by little into a fit of tears.

Those were the bad days; but there were good ones too. When Baba drove them to the beach, just an hour’s drive away from their home, they caught fish, grilled it on the sandy beach in the shade of a palm tree and ate it with fresh Lebanese flatbread.

They were sometimes accompanied by other Bangladeshi families but most often they had a hoard of men working at Baba’s factory with them.

It was on one such beach outing that the man offered to take Nauroze swimming into the sea. He was nice, she knew him quite well. The man, Ali, did not work for her father. He was new to the country and was tasked with the job of caretaker for their house. Ali was Bangladeshi and someone deeply trusted by her mother, so much so, that he would sometimes be left to babysit both sisters. During these babysitting hours, Ali would make Nauroze touch him down there. She found it odd, even knew that something about the activity was wrong. As Ali slowly fixed himself to the family’s routine, these episodes with Nauroze grew more and more elaborate. Sometimes it would be him stripping her down to her panties and touching her as yet undeveloped chest to soreness. She sometimes resisted, sometimes waited for her mother to walk in on the situation, but she never spoke of it to anyone. Even nine-year-old Nauroze knew this needed to be hidden because surely this would get her into trouble. After all, she was reprimanded that one time she fell and scraped her chin while playing catch with the kids of their neighbourhood.

These episodes with Ali gave birth to a deep fear in Nauroze. She would constantly worry that something was growing within her, something that would give her secret away. Ali left the country after falling sick, a year after it all started. But the fear did not leave Nauroze. As she moved up to her senior classes, she understood how children were conceived and that gave birth to yet another fear in her. What if she had parts of Ali within her? What if a child was being made? These thoughts popped up unexpected, while she was playing basketball with her friends, while she was walking to evening classes with a Limca and chips in hand, and it would make her nauseated, force her to puke her guts out.

Stuck in this life, Nauroze sometimes wondered of her grandmother and her home faraway in Bangladesh. Sometimes she wanted to visit that home, watch her grandmother carry a huge bamboo basket to the betel nut trees, vigorously shake the towering spiny trees and run around in the backyard collecting the small betel nuts that fell into the soft ground.

She also nursed a deep sense of fear of her father. His tempers began to get more and more erratic and he would blame her mother for every miniscule inconvenience, sometimes opting to hit her, slap her and scream profanities. Those days would be especially hard. Nauroze, her sister and her mother would huddle in a room near the pantry and talk for hours into the night.

These nights made Nauroze want to head back to her village with Ma in tow even more. Surely Baba could not beat up her mother there, because there were so many people there to stop him, to protect her mother from harm.

But going to her home would mean leaving everything behind—her school, the few friends she had managed to make and everything that was familiar, all over again, only to be plunged into another unreal newness. She would be tasked with learning the language of her home yet again. Nauroze, a mere child then, thought of all these possibilities and found her thoughts wandering off, off to a place that would finally be home, where they would all be safe. But for now, that home seemed like a far-off dream. Yet, hushed conversations in the house revealed that their life in the Middle East was drawing to a close soon. Nauroze, her mother, and sister would soon embark upon yet another journey.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments