The price of faith in China

This Ramadan, spare a thought for Muslims who find themselves on the edge of the night. Take a moment to think of Uyghurs who risk death every time they fast.

The Uyghurs are an ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang province, a region one-sixth of China’s land mass and three times the size of France. Xinjiang has historically been restive, experiencing two brief periods of independence in the last century: in 1933 and in 1944. Both times, it was violently reconquered.

For centuries, there has been a schism between Xinjiang and the rest of China: Uyghurs refer to their homeland as East Turkestan, they speak Turkic languages, and by and large, they are followers of Islam. They are ethnically different from the dominant Han Chinese, historically oppressed, and systematically underrepresented. Repression has defined much of the Uyghur experience, and separatism has simmered for decades, but it is only in the last few years that China has singled the minority out for erasure.

It has done so under the guise of countering violent extremism. For a long time, the Communist Party of China (CPC) lacked probable cause for a clampdown, but 2001 provided it with the perfect opportunity. When the U.S. declared the global war on terror post 9/11, Beijing capitalised quickly. Days after the 9/11 attacks, a Congressional dispatch reveals China’s promise to cooperate with the U.S. authorities to combat Islamic terrorism. A partnership was struck. On September 3, 2002, the U.S. government classified the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) of Xinjiang as a Foreign Terrorist Organisation (FTO). Two months later, on November 8, 2002, China returned the favour by voting for Resolution 1441 at the UN Security Council; this sanctioned the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003.

At the time, organisations such as the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) expressed skepticism at ETIM’s classification as a terrorist organisation, underscoring that ETIM might not be a Xinjiang-based Uyghur group, and that Uyghurs, most likely, do not have a unified agenda. The existence of a coordinated separatist movement in Xinjiang, too, was methodically debunked by China experts such as James A. Millward, Justin V. Hastings, and Joanne Smith Finley in academia. But that didn’t stop Beijing, and once terrorism had been minted, packaged and sold to Chinese citizens, the government initiated its crackdown. Between 2003 and 2016, Xinjiang transformed into dystopia.

Yet the question remains. Why did China single out the Uyghurs now, when it could have done so at any point in its history? Why were the first camps constructed only recently when the crackdown started much earlier? To put simply, economics, that great motivator of our times. China launched its Belt Road Initiative in 2013, around the same time as the first mutterings of concentration camps in Xinjiang came to the fore. In 2016, the CPC appointed Chen Quanguo as the party secretary in Xinjiang, a man infamous for suppressing dissent in Tibet. Quanguo acted quickly; between 2016 and 2018, large swathes of arid land were transformed into camps, schools repurposed into prisons, and crematoriums constructed to extinguish Muslim funeral practices. Today, at least two dozen Islamic religious sites in the region have been vandalised, families torn apart, and Islam referred to as a “contagion” in official CPC correspondence.

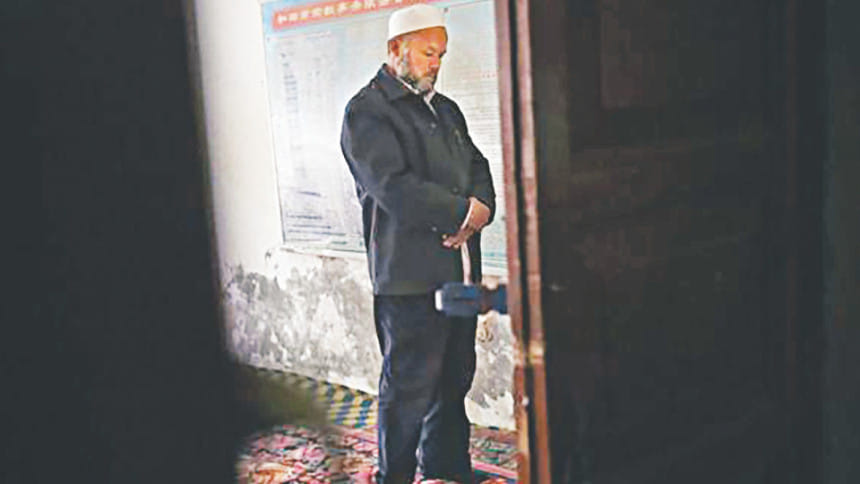

In Xinjiang’s Orwellian hellscape, movement is monitored, spyware tracks conversations online, and undercover operatives of the Communist Party report on ‘suspicious activity’. Uyghurs are routinely harassed at checkpoints placed every 100 yards or so, their biometric data is fed into government databases and their homes come equipped with QR codes. If Uyghurs grow a beard or wear a burka they get reported, if they happen to have a Quran at home they get reported, if they greet each other with Assalamualaikum... you guessed it.

Right now, conservatively, there are three million Uyghurs in detention for the crime of being Muslim. Inside the camps, inmates are force fed pork and alcohol, and chained to chairs and made to recite Chinese propaganda. This in addition to the usual: slave labour, rape, systematic dehumanisation. The full list is a Google search away.

For the CPC, there is much at stake, and human rights have never been central to China’s push for hegemony. Xinjiang’s geography puts it at the heart of China’s economic plans: Beijing’s supply of crude oil passes through the region, future highways connecting China to the rest of Asia criss-cross through its deserts. Furthermore, not only is the region rich in natural reserves, it is also the gateway to the China- Pakistan-Economic-Corridor (CPEC), a project valued at USD 62 billion.

What is happening in Xinjiang, then, is mediated by the same forces responsible for most of the human rights violations of our times: economic gain, irrespective of human cost. In China and across the globe, the rise of economic imperialism runs parallel to the re-emergence of identity-based nationalism, ignoring minority rights in favor of the ambitions of the state. To argue for it, is to choose wealth over life.

The same genocidal threads appeared not too long ago in Rakhine, and the world watched. It’s happening again, right now, in China and there’s no end in sight. The question that we must agonise over is this: why should we care? What power do we as individuals have to affect such seismic events? There’s no easy answer, but if you’re in Bangladesh right now, it’s imperative you ask yourself these questions. Only a few hundred miles away, a million refugee futures depend upon your answer.

Imrul Islam works for The Bridge Initiative, a research project on Islamophobia in Washington, D.C, and is pursuing a M.A in Conflict Resolution at Georgetown University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments