TIFF 2019: Made in Bangladesh, a melodramatic social-realism film relevant to its times

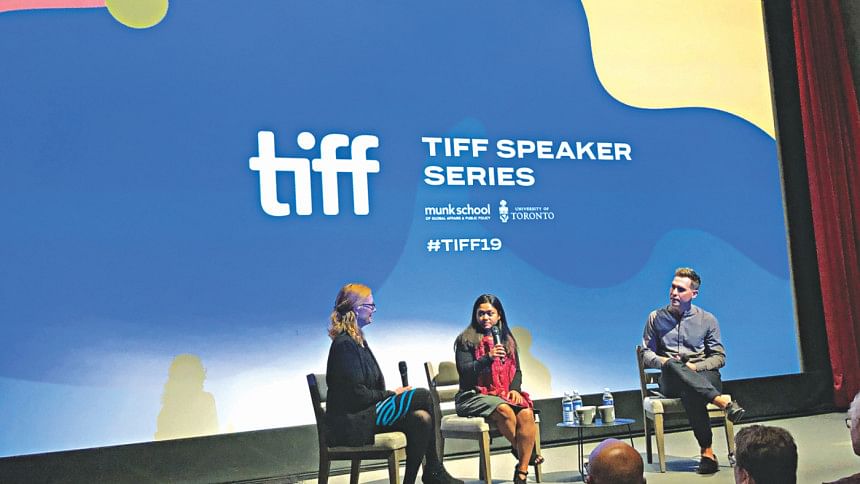

Made in Bangladesh left an impression at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) where it was selected as part of the Contemporary World Cinema programming. This is Bangladesh’s first selection in four years, the last being Meghmallar in 2015. To provide some context, TIFF ranks prime on the list of festivals and is widely considered a kick-starter for an Oscar campaign. I attended the screening of the film where filmmaker Rubaiyat Hossain was present to speak with Rachel Silvey from the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto for an extended question and answer session to provide a deeper understanding of the film.

A contemporary social drama, Made in Bangladesh zooms into the lives of garment workers at the fictional Modern Apparels in Dhaka. The film flaunts Hossain’s signature feminist stamp that is frank and fresh in the context of Bangladeshi cinema. With its working-class setting, politics of class and labour are invariably weaved into the politics of gender.

In Made in Bangladesh, Hossain brings together a globally acclaimed crew majorly comprised of women who recreate a visually muted yet aurally loud image of an informal settlement in Dhaka. Jonaki Bhattacharya who did the production design for Kolkata film Jonaki headed the set design for Hossain’s latest. The marvellous Sabine Lanceline, who has previously worked with the likes of Chantal Ackerman, joined as director of photography (DP). Lanceline’s soft, matted colour-grading heightened the documentary-like sombre tone of the film. She purposefully maintains a distance away from orientalising the poverty-stricken neighbourhood.

The film opens with the workers screaming amidst a factory fire. “Moyna! Moyna!” we hear. Immediately we learn that Moyna, a factory worker, did not survive the accident. Her memory haunts her co-workers for the rest of the film, proving to be a catalyst for most of the characters’ motivations.

Upon Moyna’s death, sewing machine operator Shimu, played by actress Rikita Nandini Shimu, is shaken into the morbid realisation that her life is as disposable as the clothes she makes. Existentially desperate and financially stressed, Shimu runs into activist Nasima, from a renowned non-governmental organisation (NGO), played by Shahana Goswami. Nasima is trying to build a report on the atrocities committed by Modern Apparel and invites Shimu and her colleagues to an NGO meeting on labour rights.

The walls of the NGO are plastered with revolutionary slogans and posters remembering the Rana Plaza collapse and the Tazreen Factory fire. The costume designer does a tongue-in-cheek job on the short-haired NGO worker adorned in a sleeveless blouse and a tip on her forehead. One of Shimu’s friends exclaim, “Nasima apa’s hair is too short—she looks like a man,” reiterating a common dismissal of working upper-class women in urban Dhaka. But through Nasima’s NGO, Shimu and her friends from Modern Apparel are inspired to unionise.

The focus of Made in Bangladesh is on the need for unions for women factory workers. The film succeeds in depicting the physical, emotional, and social hurdles created by society when a woman tries to ask for rights.

The feminist coding of this film is easy and straightforward. And due to a scarcity of Bangladeshi feminist cinema, this uncomplicated film is undoubtedly a significant one. Made in Bangladesh’s politics may be reductive and too simple for some, but it is the first of its kind. Keeping in mind that there are rarely any Bangladeshi films championing women’s rights, I can see the merit of keeping the politics simple. It is the only way that the message will get through. Masculinity and femininity work as a dichotomy within the story. All the men are evil, and rightly so. And the women are heroes for pushing back against these men with maximum capacity.

The narrative, however, treats Shimu’s jobless husband with particular sensitivity. Soheil, the husband, exhibits a soft affection towards the hard-working protagonist. He supports and appreciates her calibre only up until he finds a job for himself and no longer needs to depend on his wife’s earnings. He undergoes an aggressive transformation from the kind and loving husband to a jealous, egotistical, and domineering one that is all too familiar in Bangladeshi society.

The story also makes a remarkable comment through the imperfect friendship between Nasima and Shimu. The relationship is based on favours in exchange for monetary gains. The presence of a financial power structure between a wealthy, liberal ally and the working class adds to the story’s social-realist voice. It brings out a harsh truth that regardless of the well-meaning solidarity, there remains obvious friction between the classes in modern Bangladesh.

This friendship between Nasima and Shimu almost mirrors that of Hossain and Daliya Akhter who is the real-life garment worker and the source for the character of Shimu. Daliya was heavily involved during the inception of the script. “I wrote the script in English,” the filmmaker shared, “and then used a translator to make the first Bangla draft. But the dialogues only became authentic when Daliya’s input was incorporated—she sat with us in every reading to lend her voice to the film.”

The actors also underwent extended methods in preparing for the role. It was important for Hossain that the acting be grounded in a realism that closely resonates with Daliya’s livelihood. “I provided the costume and sandals to my actors weeks before we started filming.

They were requested to wear that attire and get in character,” said Rubaiyat in a post-screening meeting with me.

Novera Rahman, who plays one of the garment workers in the film, shared during the post-screening Q/A, “We changed our diets to match that of the workers’ and also walked with them at dawn to their workplace to prepare for the role. At one point, the factory security guards could not tell the difference between us and the actual workers.” This undoubtedly resulted in a spectacular performance fitting for the strong narrative arc.

There is also a passive presence of various other social concerns in the film. One of the workers is forced into prostitution, the landlord marries off her underage daughter to a middle-aged man, religious sermons over a loudspeaker declare women as salacious, etc. These bits and pieces are somewhere in the background, never taking centre stage—as is common in quotidian Dhaka. There’s too much going on and while one can absorb most of them, there is never enough scope to engage with each aspect deeply. It is almost as if the nuts and bolts of the cityscape make up a very loud white noise in Shimu’s life.

The highlight of this melodrama is what the narrative does in addressing the powerholders of the system. There is no room to excuse the garment owners. They are guilty of withholding payment, sexual harassment, and manhandling, amongst many other unacceptable behaviours. The portrayal of the factory owner as a villain trope works perfectly with the story’s accessible style. In the film, the suppression of the workers comes solely from the owners. Even the obstruction from the labour ministry is rooted back to the business owners—which is not a false claim to make. After all, the state functions to serve the bourgeoisie.

A bittersweet criticism is also made of Nasima the NGO worker, who refuses to go to the government office with Shimu to submit the union form and slowly fades away from the picture when the garment girls are facing pressure from the labour ministry and their workplace. Even though Nasima was the one who encouraged the girls to form a union, when push comes to shove, the working-class women are on their own.

While the film briefly addresses the role of foreign buyers, the criticism is faint. Perhaps the director is wary of alarming foreign viewers into not buying clothes in Bangladesh? Or perhaps that angle just could not be fit into the narrative at length? Whatever the reason, the role of foreign buyers is barely addressed in two lines in a short scene.

The film ends with a utopian realisation. Without giving away too many “spoilers”, I must say that the ending was not my favourite. It provides the audience with a wish-fulfilment that betrays the film’s initial socialist messaging. In conversation with Hossain, however, she insisted that she felt the ending will be successful in empowering others. “We must celebrate women’s victory,” the director claimed, “Bangladeshi women are some of the most resilient people I have seen.”

Hossain’s cinematic style and political position as a filmmaker in Made in Bangladesh brings to mind Zoya Akhter’s Gully Boy which is similarly muted in visuals but loud in its soundscape. Both are socially relevant without being radical. Both are similarly made by privileged women directors who are closer to the Western world than they are to the South Asian informal settlements they set their films in. Both films are overly explanatory of the wretched system in which their protagonists are unfortunately born into. And both protagonists attain the impossible in the end. These films are appealing to most due to the feel-good triumph of good over evil. The commendable function of these universally appealing films is that they usher in new topics into our dinner tables. That’s the power of these films.

Made in Bangladesh is a film worth appreciating for its fair criticism of the system, despite its hopeful ending. It succeeds in providing a totality, for most parts, of a system that maintains no regard for the lives at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchy. Furthermore, the film champions a female narrative using almost an entirely female cast and crew. It was fantastic being able to see so many female bodies onscreen after decades of male-dominant presence in Bangladeshi cinema. The film explores the mundane joys of womanhood, female friendship, and solidarity that are extremely relevant to our times.

Sarah Nafisa Shahid is a writer and art critic. Follow her on Twitter @I_Own_The_Sky for more art and film commentary.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments