(Uncertain) Future of Journalism in Bangladesh

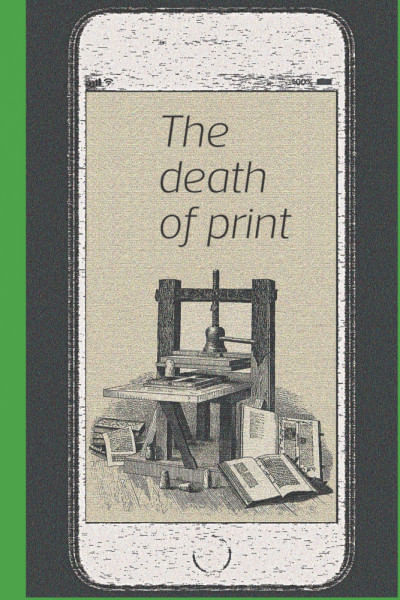

When we talk about changes in the media eco-system, we do not only talk about the medium but also the content, business models, and ethical practice of journalism. Media organisations that used to control both content and channels now only produce content; companies like Google and Facebook are the gatekeepers to audiences. Thus, business models that fund news are challenged, weakening “professional” journalism and leaving news media more vulnerable to commercial and political pressures.

In “Scanning the Shape of Journalism: Emerging Trends and Changing Culture” published in 2018, Juho Ruotsalainen talks about the rise of dialogical journalism—“instrumental” journalism that serves specific audience needs, quality over quantity, use of artificial intelligence, and a discontinuation in the shape of journalism, “moving away from an insulated field towards more open culture and practice”. The predicted trends are certainly dependent on cultural, economic, political, and social contexts.

It is hard to predict the future of journalism in Bangladesh, mainly because of a lack of research. Whatever I write here is not informed research—I am simply positing a scenario. The rise of digital journalism is a concern for mainstream journalism in Bangladesh too, but not at the same scale the western part of the world is experiencing. The press in India, Sri Lanka, and to some extent in Pakistan and Bangladesh are still the Mecca of print journalism. In fact, most of the national dailies publish online versions corresponding to their print versions. Prothom Alo has switched to a paid online version for their e-paper. We may assume it will be the trend for other newspapers in the near future. Noticeable, here, is that these online versions are built upon the credibility of the original print version—with the exception of the first online newspaper bdnews24.com. Besides online versions, almost all the newspapers employ Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube accounts.

We do not know exact numbers, but there have recently been employee cuts in established newspaper houses. Online and social media content are attracting increasingly more ads, but that is not the only obstacle the newspaper industry faces. Newspapers of Bangladesh, in fact from the days of Hickey’s Gazette, have suffered political pressure which has often ended in economic control and in extreme cases, complete closure.

Television journalism in Bangladesh could never show much promise. Only the first private channel Ekushey TV acquired any esteem for its independent journalism, but it came to a closure apparently for some technical reasons (although the misconception is that it closed down for political reasons).

Private television channels have often been criticised for their lack of professionalism—there is no guideline for television channel owners, and not all of them have professional expertise or even minimum education in this field. The popular perception is that businessmen get licenses to operate TV stations, through political considerations. The channels are known to do “he said/she said” journalism—no investigative or follow-up report. Rarely do they go outside of Dhaka unless accompanied by celebrity political leaders or people in power. Talk-shows were popular in the post 1/11 era, but they too have lost their glam. Business elites, political party members, and channel owners without any knowledge and passion for journalism control the TV channels.

Another severe problem in the journalism industry is the ever-increasing number of media outlets and shrinking market size ratio. Journalists are compromising their professionalism. Journalist associations are divided. They can confront neither the power nor the business conglomerates. The obvious outcome is to surrender to both power and business. It is at this point that journalism dies. The most frustrating thing is that an increasing portion of the limited ad spending is going to social media content which are not necessarily journalistic in nature. A big portion of telco funding, for example, is being invested in waaz contents in social media. Waaz was never covered as news in the mainstream media, but because they attract viewers, companies give them advertisements.

Moreover, as mainstream journalism suffers from lack of funding and lack of professionalism, they fail to confront the mis-and-dis-information on social media. Sometimes, the nature of invested capital also restrains them from fighting against it. Rather than confronting fake news, some journalists try to compete with them with sensational news. The discipline of journalism originated as the voice of the people against the vices of power hegemony. It seems that journalism in Bangladesh, like in many parts of the world, has forgotten its genetic promise and thus lost its path. Self-censorship is one its dominant vices.

Bangladesh will soon lose its first generation journalists who fought against the West Pakistani military rule and shaped the aspirations of a new country. After them, who will take the responsibility? How many from the next set are reliable and capable?

Digital journalism is unavoidable, as is a change in business models. Journalists in Bangladesh will soon be equipped with the necessary skills for journalism in a digital era. But simply acquiring those skills will perhaps not be enough. Many qualified young journalists are either quitting their jobs or being sacked. In the last couple of years, some of my ex-students who proved to be very good journalists—in fact investigative journalists—resigned. We recently observed mass firings in several television channels. The trust in journalism as a prestigious career is shaken and bringing back that trust is essential.

From this disarray, one positive signal I would like to reiterate—people are willing to pay for digital news content. It is the growing trend among youth, and there is a rise in subscription news. Even 10-15 years ago, online journalism would not deal with the serious long-form. But the generation today will read any length of journalistic piece online, on their smartphone—The Australian, The New York Times, The Guardian are some successful examples of independent journalism using different business models. This shows people are willing to pay for news outlets whom they trust. Quality matters. And there lies the hope.

The news industry does not need to be a mammoth one, but in the absence of independent, professional reporting providing accurate information, analysis, and interpretation, the public will increasingly search for quality news. Only equipped and ethical journalism can fulfil that demand. Restoring it is an uncertain journey, but I wish that the industry of Bangladesh takes on that challenge!

Dr. Kaberi Gayen is Professor, Department of Mass Communication and Journalism, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments