Who am I?

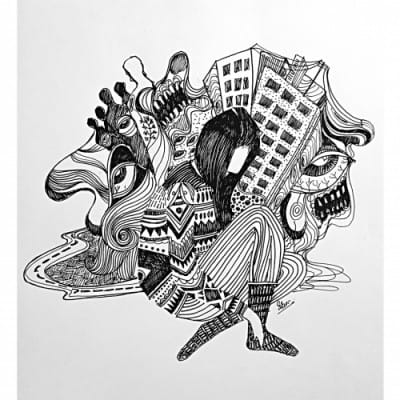

This is the fourth instalment in a fiction series about a family navigating the woes of immigrant life. It is the story of a father who suffers from psychotic breakdowns and a woman navigating different identities—that of a wife, a mother, a woman who wants to be set free, who wants to know what it is like to hold liberty in the palm of her hand. It is a story of magic and ghosts and of a village by the hills. And a story of a young woman who is gifted with an unwanted family heirloom that threatens her sanity—yet she chooses to carry it with her, allowing it to flourish, till it consumes her too.

In this edition, caught up in the whirlwind of leaving home, a teen tries to navigate life in Bangladesh after growing up abroad, tackling loneliness and fear, trying to learn her mother tongue and always, always planning her next big escape. Will she succeed or will she forever be caught up?

The packing began months ahead of time, even before they had officially decided to move, even before tickets were purchased, even before the children could talk to their school and tell their friends that they were leaving home yet again. Much like how the family had once moved from their home to the Middle East, the decision to move back to Bangladesh also came quickly and abruptly. There was not much family discussion around the great move.

Nauroze heard her parents discuss over dinner one night, after her father had returned to the Middle East, from a vacation. It was that very vacation that had changed the course of their lives. Nauroze’s father had fallen sick during that trip to Bangladesh and things had refused to revert back to normal after that.

Her father, Shafiq, had not fully recovered and refused to have his medicines on most days. It was difficult for a man like him to even admit he had a mental health problem and would require medication to manage the condition all throughout his life. His business was failing and there were rumours of another Gulf War, making him more and more restless.

The life that they had built so painstakingly in this foreign country needed to come to an end because Shafiq was finding it increasingly hard to keep up with it.

On a Saturday night as everyone sat for dinner, Shafiq brought up the big question, “Don’t you think we should go back home? It would be good for all of us.”

Uprooted yet again

Minu readily accepted the question guised as a statement.

Nauroze and her little sister Nahla, looked at their parents as they ate their Lebanese bread, lamb curry cooked in deshi style and aloo bhaji, and Nauroze felt a tinge of excitement course through her as she realised they would set sail for Bangladesh soon. But for now, she would be starting her senior year at school, while Nahla would start class two. Ma made them quickly finish their meals before tucking them into bed.

Nauroze wanted to talk to her mother about this move but Ma seemed to be in a hurry.

Minu rushed back to talk to her husband about how they could navigate this move back home. She wondered what would happen of the children’s education, where Nauroze would study. Her daughters did not even know how to read and write in Bangla, the medium of education back home. But Minu was not given any choice. Her husband’s illness robbed them of it.

“I will be gone forever”

For her first day of classes as a senior, Nauroze wore her new grey skirt and sky-blue top. She pinned her prefect badge proudly before jumping into the car. As usual, her father drove them to school—past the small Indian shops, the big supermarket, the sprawling desert, the shuk jumma (open-air market), and another little desertscape before she could see the maroon gates of her school. She looked forward to being a senior at school. Senior school would mean loads of new subjects and Nauroze was especially looking forward to her History and Civics (mostly because she liked the word “civics”) classes.

Come civics classes, Nauroze, however found herself drifting into her thoughts of the big move as Miss Princey went on and on about governance structures and the historical significance of polo games in present day Bengaluru.

By the end of the school day, she had told her best friend and most of her favourite teachers, which even included her initially strict librarian Miss Shweta that she would be leaving forever. It surprised Nauroze that they were all so worried and so full of fear for her. She could not understand it. Wasn’t she returning home to her grandmother, their big sprawling house by the hills and tea gardens, to her cousins, especially to that cousin, the one who could see through the darkness?

A whole year went by in between the announcement of leaving and their actual flight back home. But the packing continued, relentlessly, painstakingly.

Nauroze slowly cleared out her bookshelf. From her tattered Tinkle and Archie comics to her Blyton collection to all her encyclopedias—she started to fill out the boxes designated to her and her little sister Nahla by Ma. The process took longer than expected; it went on for months in fact. Mostly because as she packed, she would pluck out a book, lay near the box and leaf through the pages for hours upon hours, sometimes getting lost in the adventures going on inside the Malory Towers, or sometimes solving mysteries with Poirot.

By the time their flight rolled around, the whole house had been stripped naked. The green walls, painted by Shafiq many years back, looked even more sallow and forlorn without any contrasting furniture to offset the darkness. Nauroze and Nahla ran around the empty house, from room to room, gazing out the tinted window onto the big main road, with the huge desert sprawling just beyond the high-rise apartments that had slowly filled out their block over the years. There was not much to do in those final days, and even less to do on the day of their flight.

They did not have many relatives in the foreign country. So, the goodbyes to bid were few and with little fanfare. On D-day, migrant workers who worked at Shafiq’s factory arrived with two Nissan pick-up vans to transport all of their boxes and near about ten suitcases. Crossing the immigration gates at the airport, knowing they would never return, did not bother the family one bit. Perhaps they had not quite registered the finality of the moment.

Nauroze definitely did not understand the consequences of their move. And Nahla and the little baby were too small to even remember this life they were leaving behind.

Bangladesh

This return to Bangladesh was nothing like the vacation Nauroze remembered. Somehow the fanfare and excitement of her last summer in the village was gone. She was more grown up now, so much so, that her aunts forced her to wear the traditional salwar kameez instead of the t-shirts and pants she was used to wearing. They would not even let her go play with Nahla and the other kids, because she was a big girl now and would attract undue attention.

All of this felt strange to Nauroze. Was she not touched all over, in all the places that she now has to cover with a scarf, by a man she had never seen before and would never see again, save that one mad year? Still, she did not protest. She did not have the capacity to even voice what it was that had disturbed her about their strange impositions.

They stayed on in the village for another few months, before Nauroze’s parents decided it was time for her to be sent back to school.

But Nauroze could not read or write in their native language which meant she would have to start afresh or from a much lower grade than she had been in back in the Middle East. This knowledge disturbed both Nauroze and her mother. She did not want to go to school in the village, she did not like the look of the classrooms, and she definitely did not want to start in a lower grade.

This gave birth to much debate in the house. Nauroze tossed and turned in bed as she heard chacha, chachi, choto fupi discuss over her future.

“No, no you cannot move to Dhaka. The girls will come under bad influence. It is a big city, you cannot raise them alone. And bhai is pagol (mentally ill). He will spend all the money and you guys will be driven to the streets!” screamed choto chacha.

Fupis were not far behind with their advice. It took many more weeks of back and forth before they finally decided that Nauroze would go to Dhaka. Yet again, another fate was sealed over dinner.

And that is how, just two weeks later Nauroze found herself in a small bungalow opposite a little graveyard in Dhaka. She did not recognise the streets, neither did her parents, but they chose to get her admitted to that school. The reasons for this were simple: the school would teach in English and it had a housing option.

Nauroze did not say much, in fact, she did not say anything as they went about enrolling the 1-year-old into this school that would moonlight as her house during the nights. And then one fine October morning, her mother and father dropped her inside the premises and walked away. Nauroze had not shed a tear all this time. But after her mother walked out of the room, Nauroze ran to the verandah and watched as Ma’s frame became smaller and smaller on the walkway.

Days and nights in confinement

The room had three beds, all empty except for the one occupied by Nauroze. The school was not very popular, and she was the only female residential student. A female supervisor had been assigned for the care of the female students but that lady, too, had quit just days before Nauroze moved in. On that first night, Nauroze laid out the bedsheet in the corner bed and tried to hang up the mosquito net. It was her first time attempting the task. She struggled to hook the net the right way so that it would stay up and not fall over her face, smothering her.

Somehow, she managed to keep her cool for the first few days. In the mornings, she would be served a breakfast of banana and bread, for recess two samosas, for lunch two pieces of chicken in a watery broth, a bowl of some bland vegetable that was in season.

Classes took place in the backyard of the building. Students who did not live in the dorm studied here too and Nauroze would watch longingly every afternoon when their parents came to pick them up.

It did not take too long for the loneliness to hit. But it came in waves. Nauroze enjoyed the first few days away from family. She would stay in bed on Fridays and read endlessly because there was no one to wake her up. Nearly 15 by then, she relished these sudden bouts of freedom but she also missed home. She missed the food Ma would make on Fridays. She hated these bread and banana breakfasts and sorely missed the elaborate breakfast spreads of home, sausages, eggs sunny side up, and on special days, khichuri and lamb curry.

As the days went by, she sat in the verandah for hours, praying to be released from this place, praying to be able to see her mother, or talk to her at the very least. She did not shower for days, and sometimes, she snuck to the kitchen behind her room to try to steal the good food being prepared for the family who owned the school premises.

Planning the big escape

The thought of running away from this godforsaken place came in a sudden, decisive moment. Nauroze planned the whole thing in her head. She had some pocket money left from her father’s last visit which she guarded with her life. She would use it to take a CNG to the train station, buy her tickets, and go home. It was nearly seven months in that confinement, broken by occasional visits from her father and her short vacations back home, after which Nauroze made the escape plan.

She knew she had to make a run for it when the guard opened the main doors in the morning and went for his morning prayers. She would have to sneak out so that she could cover a good distance before anyone realised she was missing.

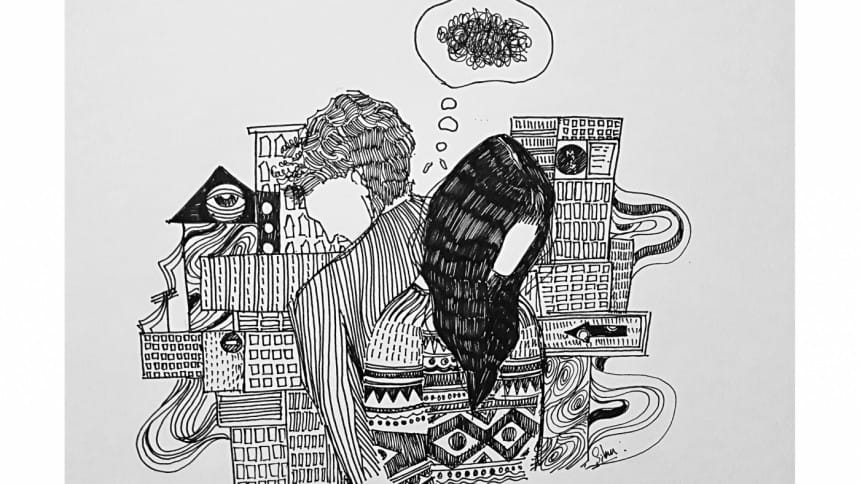

She spent the night before the escape tossing and turning in her bed, unable to fall asleep, unable to make up her mind. This is what her chacha and chachis had warned her mother against; that Nauroze would turn out to be a bad egg, one that eloped from school and brought shame to her parents.

These thoughts scared her.

“What if my parents do not accept me back into the house? What if I never get to go to school again? Escaping school would surely mean I have failed.”

Nauroze’s thoughts spiraled out of control that night. When she woke up the next day, she realised she had overslept through the morning prayer time of the guard. She was stuck here yet again.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments