Who is fantasy for?

If I say fantasy, what do you imagine? Castles, knights, dragons, and different fantasy ‘races’ (by which one means dwarves, elves and humans, all generally analogous in appearance to the real world white ‘race’). Indeed, as an aspiring fantasy author, my own forays into worldbuilding began with a European base, with non-Western cultures treated as foreign—I, a brown author, did not automatically consider people who looked like me to be fit fantasy protagonists.

This is not natural. Fantasy is not inherently a magical vision of a Western, Anglo-centric historical past starring white characters. Yet it automatically feels that way because of defining works that have operated in that framework, right down to the genre’s Bible, The Lord of the Rings.

Here’s some damning evidence in J. R. R. Tolkien’s post-mortem trial for racism. The orcs, a species fundamentally predisposed to mayhem and cruelty, were described in one of his letters as: “...squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes; in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types.”

For a fan, it’s tempting to latch onto the mitigating language—”Mongol types” after all, not actual Mongolians, and the ugliness of the ‘least lovely’ of these people is filtered through European preferences and not an outright implication that Central Asians are ugly. The statement may be nuanced, but the nuance does not redeem the obvious racism.

It’s important to differentiate between structural and personal racism. Tolkien hated allegory, but his work retains unconscious metaphor and shorthand; what we may call coding. When Tolkien coded the dwarves as Jewish, he (likely unconsciously) played into the stereotype of a wealth-obsessed race who are inferior to the more Western, Christian-coded elves and humans. The same man was the opposite of racist when he took a deliberate, explicit stand against white supremacism and fascism. In that sense, he was braver in his personal life than many of his peers, but his work nevertheless betrayed the racist assumptions of his time. And it is his work that went on to create the new mythology from which fantasy would draw henceforth—as undeniable an influence as the Germanic tales that inspired his own writing.And so, the structural, unconscious racism present throughout Tolkien’s work became a part of that bedrock as well.

The 21st century has transformed fantasy from something with niche appeal into a pop culture powerhouse. The Lord of the Rings in literature and film, Harry Potter in all its forms (including its current zombie-life), Game of Thrones (and the A Song of Ice and Fire books by proxy), and video games such as The Elder Scrolls (more specifically the fifth one, Skyrim) and The Witcher aren’t just influential in their respective media but are unavoidable mainstream phenomena. Dungeons and Dragons, portrayed even as recently as in Stranger Things as white boy basement geek subculture, is now cool. With the mass consumption of fantasy media, the faults in its foundations become more visible and dangerous.

Who is fantasy for?

The casting of people of colour as villains in the Lord of the Rings has been justified by fans with the argument that Tolkien was an author creating a fantasy vision of England. His was an English imagination, so naturally those very different from that culture would play the role of the enemy; it is a strange twist of logic that claims the demonisation of the Other as not racist simply because the writer didn’t think about it. Tolkien’s identity as a white Englishman growing up during a culturally insular period is used to defend his creation of Middle Earth as a white, English world where people who look like me and the bulk of The Daily Star’s readers are the villains. It wasn’t ever written for us. This is similar to the argument used to defend another author whose work is quite blatantly an allegory for English history—George R. R. Martin.

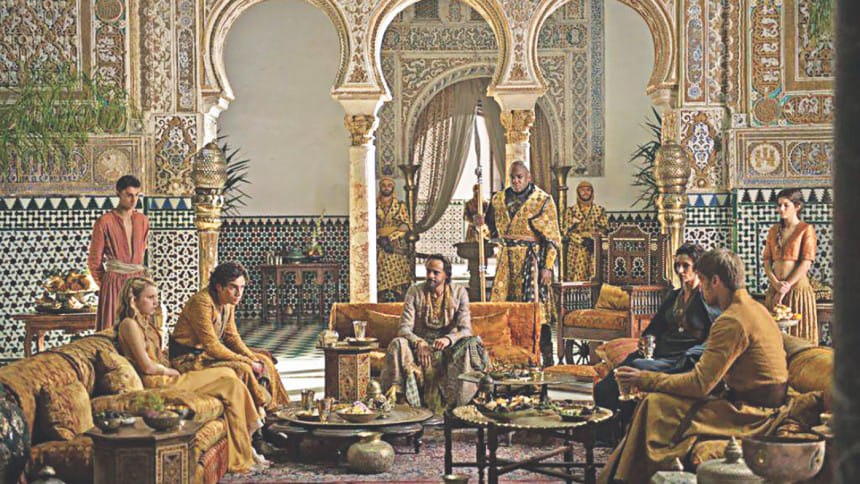

Game of Thrones is now down to two people of colour in speaking roles, and they are minor; the rest were nameless cannon fodder. This was not by malicious intent, but an acknowledgement that this was always a white story.

While HBO’s Game of Thrones and A Song of Ice and Fire are distinct entities (to the show’s increasing detriment), the TV adaptation’s depiction of exotic eastern barbarism in the form of the rape-keen Dothraki, the eunuch armies of the Unsullied, the slave economies, and all the intrigue and sorcery of Essos are right on the money in terms of translating the books’ vision. In A Song of Ice and Fire, Westeros is the place where the more ‘normal’ story based on the history of the UK—relatable to the unconsciously intended core audience of white, Western readers—plays out, whereas the rest of the world is darkness and exciting mystery. (In fact, the books go even further than the show to exoticise both the East and the South.)

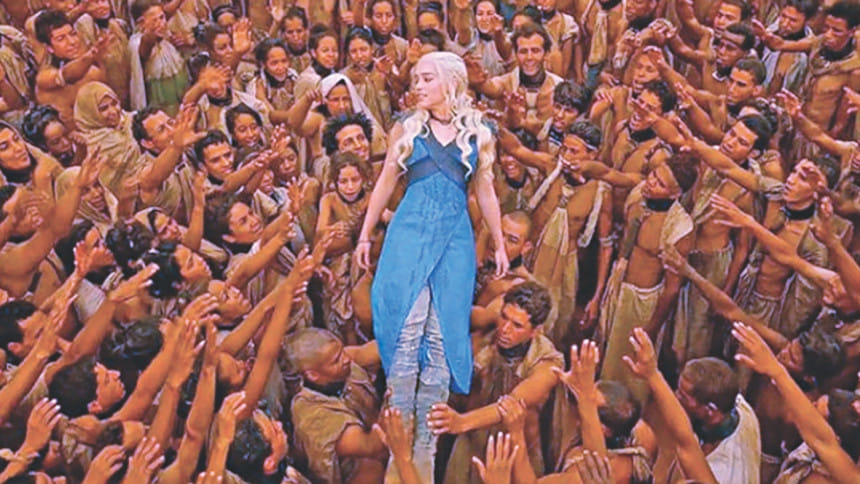

The Anglo-centric point of view of Westeros as the fictional launchpad gives us such things as Daenarys’ entire storyline, a white saviour narrative that is arguably the prime reason we even get to encounter the other cultures of GRRM’s world. It is a white saviour narrative unconsciously, according to interviews given by GRRM—and we may give him the benefit of the doubt (the famous scene in the TV adaptation where Daenarys crowd-surfs freed brown slaves was, according to him, a consequence of filming in Morocco and hiring local extras). The unconscious nature puts this racism in the same category as Tolkien’s: it is made possible because built into the premise of A Song of Ice and Fire is an idea of what kind of people the story is for.

GRRM almost certainly holds no more actively bigoted views of non-white, non-Western people than the average person (by 2019 we would have found out if he did.)What he does instead is operate in a genre that not only allows him to exclude and otherise most of the world, but in fact encourages him to.The assumption of the Western, white gaze for the reader allows GRRM to explore the cultures of Essos as strange, wild and exciting compared to the relatively stodgy and predictable places of most of Westeros. To a degree there is an in-universe cleverness to it due to his use of first person point-of-view narration: we see Essos through the eyes of the Westerosi-oriented, principally white cast of characters, and so naturally all that is odd and different takes the foreground (much like Tolkien’s caveat of “to Europeans” when discussing Orcish appearances). Yet, we do not see the gaze reversed: Essosi, the people of colour, are not viewpoint characters who reveal what their cultures are really like under the surface, and we do not see their thoughts on Westeros and its equally violent, feudal systems and strange zombie armies.

This is not about ‘forced’ diversity, but rather a reckoning of the way the inclusion of non-white peoples and non-European cultures has been handled. Indeed, one wonders why authors such as Tolkien and GRRM even included non-Western cultures and non-white peoples if they had nothing better to do with them than exoticise or demean them. It is one thing to be told, as JK Rowling did (originally), that hers was a white cast, and not to see myself in them (except for the most token represenation); Harry Potter is a story not ‘for’ me but which I nevertheless enjoyed. It’s quite another matter to see ‘myself’, but as sinister and debased.

In fact, how ‘forced’ would diversity even be? The treatment of non-white and non-Western cultures in fantasy is of political relevance. White supremacists have long attempted to co-opt fantasy as an escape from an increasingly multicultural, globalised world, with fantasy depictions of a homogenous, white world with dark-skinned others (who may even be non-humans such as orcs). As more and more people of colour consume fantasy media, there are increasing criticisms of franchises that erase, exoticise or demonise non-white, non-Western peoples and cultures. Such critics are often met with the counter-argument that because most fantasy media have European cultures as a baseline, whiteness is a given. After all—the West is white, isn’t it?

Not at all, in fact. Fantasy media seek to replicate specific times and places in history, but as with most historical projects they reproduce very limited visions of the past. Europe’s past has always been racially mixed to a degree fantasy authors and contemporary politicians from those countries have ignored. The presence of people of colour in Europe for thousands of years is a historical fact that is rarely addressed in fantasy. Indeed, what constitutes a person of colour—a non-white person—is not historically fixed. The West as a whole is a relatively modern trope, and the West as white is an even fresher idea, and made starkly clear in the current place of Eastern, Southern and Central Europeans and cultures into the wider concepts of the West and whiteness. Tolkien’s vision had little room for Greeks or Magyars, it wasn’t long ago that the Irish were depicted in newspaper caricatures as monkeys, and the European Union is still very much a Northern and Western European core. European homogeneity is a myth that falls apart under even mild scrutiny. If what is white and Western today really isn’t that under the surface, then how do we imagine that such homogeneity existed centuries before?

The fantasy of whiteness is made starkly clear in the case of the Witcher games. The third installment was critically acclaimed, which gave it mainstream appeal; alongside that came the inevitable question of where the people of colour were in The Witcher 3’s lovingly-detailed world. The canard that it is set in a culture based on Poland was raised in defence of this, though it is nonsense to claim that everyone in medieval Poland was white. Indeed, the exclusion of Poles from the standard white vision of fantasy formed a crucial part of the defence; The Witcher was a flagship for representing previously unexplored Slavic cultures in fantasy media. The discourse around it exemplifies the curiosity of Otherness: Slavs were not Western white enough for traditional fantasy to represent them, but when discussing the exclusion of more explicitly different people such as Middle Easterners or even Europe’s own Roma populations, whiteness and Europeanness served as rallying points. The Netflix adaptation of The Witcher may potentially cast a person of colour to play a half-elvish character, and this caused controversy; that the protagonist’s role is to be played by Henry Cavill, who is no Slav, raised little ire.

The racism of fantasy in constructing inclusion and otherness, conscious or otherwise, is being challenged equally by franchises such as The Witcher and everyone asking why the Dothraki were the first to die in the recent episode of Game of Thrones. In different ways they are reactions to systemic assumption baked into the foundation of the genre of who the story is for. The mainstreaming of fantasy will make it increasingly clear to people of colour and to those who do not see ‘their’ past in the images of knights and dragons that they will have to be their own storytellers. Dungeons and Dragons and tabletop RPGs in general are increasingly popular among players who are people of colour, who are women, who have LBTQI+ identities, as it allows them to create their own forms of escapism and empowerment.

In the meanwhile, we will continue to read and enjoy the works of old white men, because we are all products of society. I personally do not play the game where a creator has to be pristine, especially against standards that have evolved. This does not mean we should ever be silent in our criticism, only that we understand the system rather than the personal nature of most fantasy racism. To criticise the system will allow us to see better, more respectful inclusion in future works, while not really holding a personal grudge for short-sightedness.

By which I mean you can hate HP Lovecraft all day because he was intentionally racist. He was all about that stuff.

The writer is an artist and an MA candidate in International Migration at the University of Kent. Read more of this sort of thing in Disconnect: Collected Short Fiction.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments