Frida in colours of capitalism

Before she made it to our saris, chunky jewellery, phone cases, and magazine covers, Frida Kahlo was a genius, a socialist, a feminist, and an anti-imperialist nationalist, whose mere presence in history is radical. Her art challenged norms during her time and continues to do so today—if only we are willing to engage with her art on her own terms rather than through our liberal, bourgeois, feminist lens.

Frida was born on July 6, 1907, in Mexico which means that she would have been 111 this year. She later chose to celebrate her birthday on July 7, 1910, the year of the Mexican Revolution, making her a 'Child of the Mexican Revolution'.

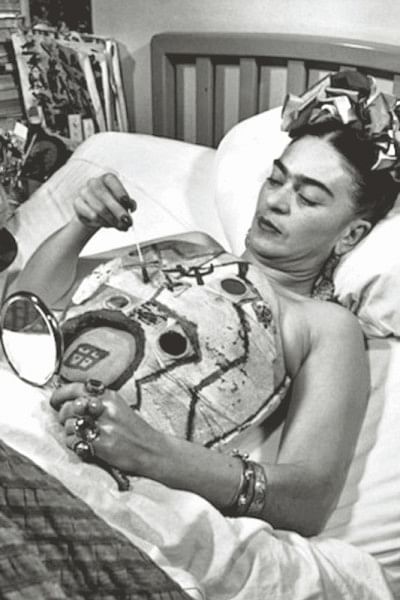

Frida was undoubtedly ahead of her time. Her self-portraits are jarring, dealing with her disabilities, social disparity, her sexual identity—she openly dated men and women—at a time when it was deeply frowned upon and even unacceptable. She is a non-conformist who painstakingly and purposefully worked to create a persona that was powerful and political. She was a staunch leftist; her political identity was not covert. Part of the Mexican Communist Party, Frida also made no secret of her distaste for American capitalism. She was a trailblazer not just for women, but for LGBTQ people, and people with disabilities. After a tram accident which changed the course of her life, she struggled with and embraced her multiple identities, which can be seen in her self-portraits, making up the bulk of her work.

Frida eschewed trends. At a time when French fashion was at the height in her country, she chose to dress in the traditional huipil tunics, enagua skirts, and headdresses, exhibiting her love for her Mexican Mestizo identity and heritage. Likewise, the indigenous flowers she wore in her hair and the native jewellery she used to adorn herself with, were also reflections of her nationalist stance. Art-historians look at Frida's choice to wear her traditional clothes as distinctly political and they argue that it allowed the artist to be more in tune with her country's pre-Columbian cultures in post-revolutionary Mexico.

After having spent some time in America, Frida returned to Mexico and painted Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States (1932), printing Ford's name across the smoke-belching factory chimneys on the US side, showcasing her deep distaste for American capitalists. "I'm more and more convinced it's only through communism that we can become human," she wrote to an American comrade after the trip. Yet to experience her posthumously, raking in financial gains for businesses, boutiques, furthering the capitalist cause feels like a special kind of irony.

But try as she might, Frida cannot escape the cult-hood status she has been exalted to. Far from the West, here in Bangladesh too, she is having a moment. She is on saris being sold at exorbitant prices, on jackets, mugs, earrings, pillow covers, fridge-magnets—you name it, chances are, Frida has been flattened, reproduced, and reprinted hundreds of thousands of times, helping to generate revenues. This adulation of Frida, limited to the superficial, simply celebrating her as a style icon, goes to undermine her ethnicity, her disability and her principles–all of what made Frida Kahlo, the icon that she is today.

The 'sanitised' Frida Kahlo idolatry and the wave of commodification surrounding it, is not completely bad despite the many misgivings I have with it. It does make sense to see a resurgence of Frida Kahlo, a socialist figure, in Bangladesh, a country founded on principles of socialism. Yet, to see a watered-down narrative that is simply limited to trite symbolism leaves the story half-told.

Frida challenged beauty norms, her unibrows and light moustache, a testament to her rejection of the then and present beauty standards. While Frida's radical aesthetics has the potential to challenge Euro-centric beauty standards in Bangladesh, her white-washed representation in our pop culture, with fair skin, moustache-free upper lips, and lightened unibrow, actively reinstates the Eurocentrism and able-bodiness that she so adamantly resisted. In Bangladesh, Frida is not a radical Mexican feminist, but a cultural icon imported from white, Western media. She stands for every day, mass-market, feminism targeted towards able-bodied, cis-gendered, privileged women.

Thus, echoing a very timely and hard-hitting article on Dazed titled "Frida Kahlo is not your symbol" which says, "This ultimately leaves her inaccessible to minority groups while simultaneously allowing privileged people to embrace her without having to come into conflict with aspects of her that contradict their behaviours."

And, thus leaving Frida's legacy in peril. Will Frida remain simply a face on our t-shirts and saris, palatable as a cool figure? Or will Bangladesh, where feminism too is experiencing a new-found momentum, give Frida a full homage, where we will see her as she would want to have been seen? Complete with her politics, struggles, and sexual identity?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments