A law to gag your online freedom

Less than a month after Bangladesh's cabinet approved the 'Digital Security Act 2018' in late January, Human Rights Watch, a top rights group, published a strong response in its website. Pointing out the vagueness of Section 31 of the draft act, which would criminalise posting of information that "disturbs or is about to disturb the law and order situation," HRW said, "Almost any criticism of the government may lead to dissatisfaction and the possibility of public protests. The government should not be able to punish criticism on the grounds that it may 'disturb the law and order situation'."

To put this in context, the government could use this provision to bring charges against those whose Facebook posts called on the public to take part in the recent anti-quota movement arguing that it "disturbed" the law and order situation. Furthermore, the police could arrest anyone at their discretion without any warrant from the court. This scenario was confirmed by two legal experts I spoke to.

"In fact, that is precisely what the government intends to do: using the law to suppress critical voices," Supreme Court lawyer Jyotirmoy Barua told me. "The scenario you hypothetically painted will be real in ensuing days."

While it is seemingly impractical for the government to press charges against so many people who wrote in support of the protests, the mere possibility that it could do so if it wanted highlights the dangers that this law poses to freedom of speech and expression. Yet, defying all protests, concerns and public opinion, the law was placed in the parliament on April 9 and is expected to be active within weeks.

Section 31 is hardly the only problematic part of this law. In a January 29 report, The Daily Star published a table showing that the proposed law was harsher than colonial-era laws in some respects. The Act, for example, promises three years of jail for defamation, in comparison to two years' jail for the same offence during the colonial era. On the other hand, there's a growing global consensus that defamation should not be considered a criminal offence whatsoever.

Similarly, Section 28 of the Act would impose five years in jail for speech that "hurts religious feelings," although it requires prosecutors to prove that the alleged offender had deliberate intent to injure other's religious feelings. In spite of the intent requirement, this section is incompatible with global standards. The European Court of Human Rights noted in the landmark Handyside vs UK case that freedom of expression is not only applicable to information or ideas that are generally received favourably, but also to those that may "offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population."

Mr Barua also points out the disproportionately harsh punishment for light offences. "You cannot hang a man for stealing a cow. There must be some proportionality between the crime and punishment for it."

Multiple ministers touted the Act as a better alternative to the much-criticised ICT Act's Section 57. However, as reported by The Daily Star, the Digital Security Act actually splits the offences in Section 57 into four separate sections—21, 25, 28 and 29—with varying ranges of punishments.

Far from providing relief from the repeal of Section 57 of the ICT Act, the Digital Security Act is more draconian than the law it intends to replace, legal reviewers and experts say. Not only has it retained almost all problematic aspects of the ICT Act, but the Digital Security Act's Section 32 has also triggered particular concerns within the journalist community as it criminalises secretly filming in government offices or taking confidential documents using digital devices.

Section 14 of this law criminalises spreading "propaganda and campaign against liberation war of Bangladesh or the spirit of the liberation war or Father of the Nation." Initially, the section was widely believed to have been inspired by Holocaust denial laws that exist in 16 European countries. However, the final draft went way beyond just criminalising denial of genocide in Bangladesh's liberation war and could prove to be a detriment to future academic research on the war.

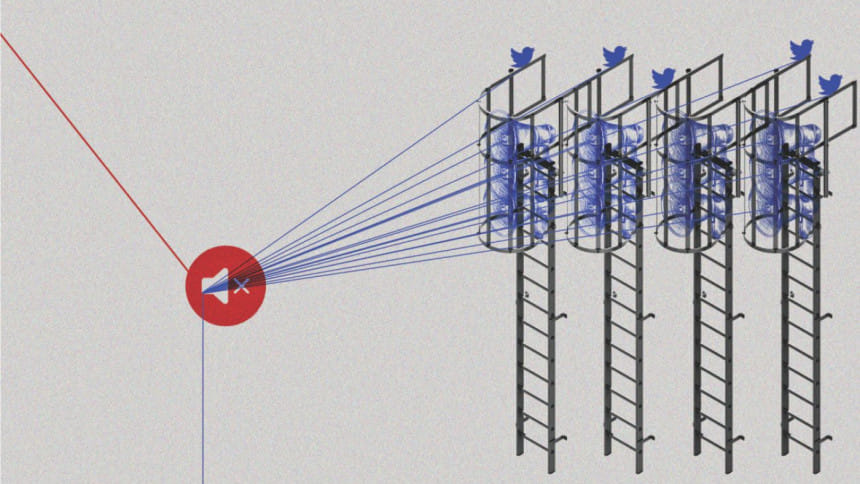

Above all, the most problematic aspect of this law is that it contains some provisions that are so vague that virtually anyone could land in jail for writing anything critical on digital platforms. Human Rights Watch identified at least five different provisions of the law, which criminalise "vaguely defined types of speech". For example, Section 25 would authorise sentences of up to three years in prison for publishing "aggressive or frightening" information, leaving wide scope for the government to prosecute any critical speech.

"A law must be clear and foreseeable. The language of the law must be so that a reasonable person can understand the consequence of his action," Arpeeta Shams Mizan, a Harvard-trained law lecturer at the University of Dhaka, explains. "He or she must understand whether the action s/he will be doing may violate the law in question."

HRW also pointed out that such overly broad provisions of the law may also increase the likelihood of self-censorship to avoid possible prosecution.

"The action that is criminalised must be clearly defined. If it is not specifically defined, then it means you keep a scope to detain or harass people under a vague pretext," Jyotirmoy Barua says. "This is the common feature of some recent laws: keeping some loose ends to use them as per their own interpretation to frame anyone critical of the government."

Nazmul Ahasan is a member of the editorial team of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments