The Problem with Straight Intentions

On June 13, 2019, each of us received frantic messages from our queer community friends in Bangladesh. One of the messages said, "Another fiasco! Please someone… email her and ask her to stop this madness." The "madness" was referring to a recently minted Facebook event page which announced the Bangladesh LGBT Pride March 2019. The event page had a public guest list and mentioned a specific location in Dhaka where the pride march would take place. Still recovering from the 2016 killings of LGBT+ rights activists in Dhaka, LGBT+ community members were shaken. Some were reliving their trauma. "My body is shaking," one of them wrote to us. "I am having 2016 flashbacks," another said. The host of the event, as we later confirmed, was Shammi Haque, a blogger who is currently an asylee in Germany since her departure from Bangladesh under fatal threats in 2016.

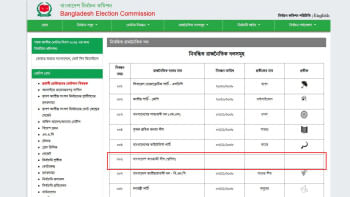

Haque, an independent advocate of civil rights and self-identified cis-heterosexual woman, is not affiliated with any LGBT+ rights organisations in Bangladesh. Virtually nobody in the Bangladeshi queer community seemed to know about the event before the page was launched. In fact, nobody knew Shammi Haque. Many assumed the event was a targeted effort to out queer people. In an atmosphere of panic and confusion, community members reported the event as fraud and scam. Shammi's intention in creating the event, as we found out in personal communications, was to create a virtual pride parade, generate conversations, and make the event go viral. Haque's astroturfing approach to fighting for queer rights is a paradigmatic example of how depoliticised and disorganised allyship is counterproductive to social movements and damaging for the most vulnerable people in our societies.

Although after approaching her about security issues Haque made the guest list private, the guest list was publicly accessible for hours prior. Creating a hit-list based on social media profiles is a known pattern among vigilante groups as seen in the past few years' attacks on Bangladeshi bloggers and activists. Why Haque would create an event with a public guest list remains unexplained, if not assumed to be downright irresponsible and ill-willed. Haque, living in the relative safety of an asylee, endangered queer lives in Bangladesh.

In the event page, Shammi Haque listed four demands: abolish Article 377, legalise homosexuality and same-sex marriage, bring justice to Xulhaz and Tonoy's murder case, and provide state apology to queer community. While these demands are meaningful, committed organisers dealing with the day to day struggles—homelessness, unemployment, lack of healthcare and financial support for education, internalised oppressions, trauma, suicide, and violence to name a few—of the queer community in Bangladesh are relying more on the slow work of learning to care for each other, surviving and making life amidst fear of death. Grounded organisers, with their lives at stake, understand that procedural justice and legal changes will come about as a result of developing collective resources, support infrastructure, and deeper community bonds across class and other lines of difference. In fact, that camp of organisers may argue that if the social consensus around heterosexism, and criminalisation of non-normative genders and sexualities does not change, then making legal changes will not lead to any sustainable societal shift in the country. There are also those who found Haque's event page exciting and support such expeditious efforts at confronting the patriarchal-capitalist state head on. Haque's demands were, therefore, met with either a sudden rush of romance, with outrage or a wave of incredulity. One organiser, who has been conducting educational workshops around Bangladesh, commented that Haque's attention-seeking and security-threatening action will "take current organising work several years backwards."

Nobody in the queer community, as far as we witnessed in multiple social circles, were opposed in principle to Haque's right to create a social media campaign or to air her opinions. It was her agent provocateur approach that was under scrutiny. What if some people in good faith did show up at that location? What if the police and extremist groups got involved? At the heart of all contentions was the fact that Haque was speaking for us without speaking with us. Had the decision been reached through collective strategising and through negotiations within the community, the reaction might have been largely different. "How can a woman just fly in virtually and start speaking on behalf of the queer community?" some asked, indicating in sub-text a situation where Shammi Haque was positioning herself within the tired trope of a celebrity saviour saving helpless people in a faraway part of the world. Others were frustrated, "She cannot just speak for an entire movement and put us in danger like this." Some gave up and said, "Well, what can we do? We don't own the movement. We can request her to take it down but at the end of the day we can't take down the event." In the whirlwind of messages, we learned that the Dhaka Metropolitan Police was tagged to the Facebook event. In the days following, sub-groups were formed to think through precautionary, legal, and emergency measures. Active organisations decided to slow their organising or go underground if the moment required.

When community members approached Haque about taking down the event on grounds of security and the unethical approach to organising a pride event and drafting demands, Shammi Haque refused to compromise her "freedom of speech" and further suggested that LGBT people can't achieve their rights without sacrificing safety. Haque's response made some ask, "Why are we required to beg an ally for our safety? Doesn't she see how much emotional labour she is demanding as an ally just in order for us to convince her that she should not compromise our lives?"

Haque's virtual campaign, intended to create conversations and support the queer community, generated confusion, a sense of helplessness, and heightened the atmosphere of suspicion and mistrust in online communications. A vulnerable community that was regaining its foothold was thrown open to violence in a country where activists generally have been struggling with threats of violence. Some agreed to form an ad hoc coalition of different LGBT+ organisations and write a statement urging Haque to take down the event. One person warned, "We should not piss her off. What if she does something worse?" The equation was clear—Shammi Haque was beyond any accountability or direct consequences for her actions given that she was located in Germany. The Bangladeshi queer community was powerless and could only watch as violent comments poured out in reference to the event page. Screenshots of the event circulated among extremist social media pages. Not every comment was hateful. There were supportive messages on and off the event page. But there were enough violent comments to raise the alarm: "All of you will be killed." "They should be killed with direct firing." "Their wings are growing. We have to break them." "Worse than animals." "Homosexuals need mental treatment." "They should be burnt." "Kill them." Ultimately, considering the provocateur role that Haque had taken on and her uncompromising attitude, the completed statement was not published.

I. Sayed is a queer poet and writer from the Bengal delta. Rasel A. is a community-based filmmaker, queer archivist, and exiled founding editor of Roopbaan magazine.

This article was first published in Medium.com.

Comments