Not just a one-hour test

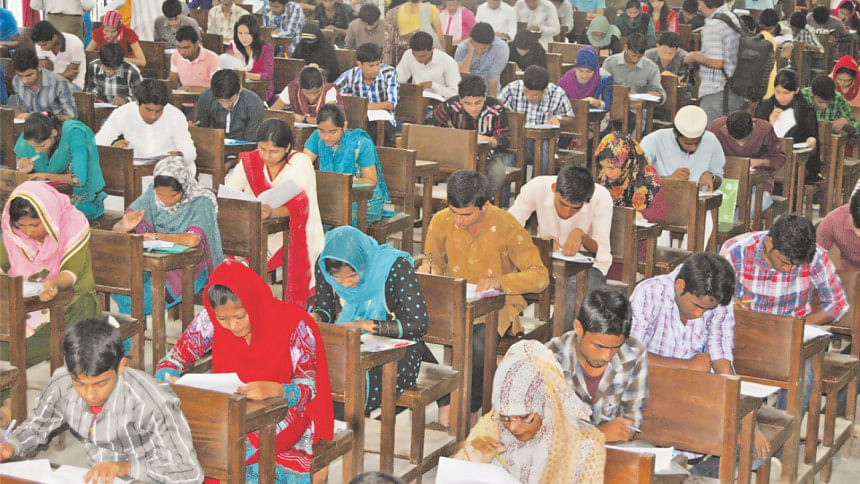

University of Dhaka (DU) undergraduate admission tests remind us that you only live once; after all, there has been no second chance for test-takers since 2014. While the DU authority opens its doors to its Master's programmes allegedly through non-competitive examinations for monetary considerations, the university slams its door shut to fresh HSC (Higher Secondary Certificate) graduates who fail to make the right first impression in the highly competitive admission tests.

While admission seekers from all educational backgrounds can sit for DU tests based on their stream of study, the acceptance rate is very low. This year 37 candidates competed for each DU seat—eight less than the previous year. Students receiving formal education from madrasas were previously ineligible from choosing certain DU disciplines such as Women and Gender Studies, English, Bengali, Linguistics, and International Relations, as they apparently did not meet the prerequisites. Fortunately, they are now allowed to apply for those subjects. The tests, however, fail to attract a large pool of English Medium students whose General Certificate Examination (GCE) syllabi do not match that of DU freshman admission tests.

Records are meant to be broken. The number of GPA 5 achievers reminds us of that every year. But the ratio of top grade achievers to those passing the DU entry test is, surprisingly, very low. This year 85.25 percent students failed the DU C (Ga) unit admission test—9.23 percent fewer than the last year. 83.44 percent, on the other hand, could not the pass the B (Kha) unit entry examination—5.13 percent fewer than the previous year. Needless to say, we need to look beyond the numbers. Mere growth in pass rate and GPA 5 inflation cannot take a country far if simultaneous gains cannot be ensured in elevating the standard of learning and teaching.

Former DU Vice-Chancellor Professor AAMS Arefin Siddique said, "The DU admission test is a process of elimination through competitive processes as the number of seats is very limited. In the academic session of 2014-15, for example, we could only entertain 6,700 from among 301,800 applicants. The scenario has not changed much, though 253 more seats have been added for the undergraduate programmes of the 2017-18 session." Though the university's evaluation method is neither a yardstick nor an indicator of the quality of education in the country, a part of the questions examine knowledge on previously studied subjects. It is expected that students meeting the eligibility criteria for attending the test would, at least, secure pass marks in English and Bengali.

Primary education is free for all children in Bangladesh, from grades one through five. However, the quality of education remains a barrier for education levels (UNICEF Bangladesh, 2017). A 2016 World Bank report finds that, in general, Bangladeshi students have weak reading skills, while curricula, teaching approaches, and examination systems at all levels focus more on rote learning than on competencies, critical thinking, and analytical skills. Low educational standards at early levels affect the tertiary education of the country. Students coming out successful in the HSC examination cannot apply their knowledge of whatever English or Bangla they are taught for 12 years in the examination halls, let alone to the real world.

The national learning assessment conducted by the government of Bangladesh also shows poor literacy and numeracy skills among students: only 25-44 percent of students in grades five through eight have mastery over Bangla, English and Math (World Bank, 2016). Educational divide across the country adds to the conundrum.

The methods and processes that DU employs, too, have their limitations. The General Knowledge (Bangladesh and international) segment of B and D unit question papers are often randomised and too general. The same question pattern is set for the would-be students of Arts and Social Sciences, which is far from appropriate. Disciplines such as Economics, Development Studies, International Relations, and the likes require specific aptitude and cognitive abilities. The Social Sciences and Law demand critical thinking skills from their students which are not reflected in the over-generic B and D unit questions.

Which elephant came from India and died in Bangladesh recently? Under which tree was the old woman of the story "Aobhan" laid to rest? Helsinki is the capital of which country? Questions like these that, miserably, try to assess the memory and memorisation skills of candidates cannot cater to the need of teaching and learning certain disciplines.

DU undergraduate admission tests, ultimately, turn out to be a routine check-up of how well one prepares oneself for the test. It does not reveal how intelligent and knowledgeable a student is. Holding separate exams for certain disciplines and faculties will not be an uphill task for the DU authority as one of its autonomous institutes (institute of Business Administration) has been taking SAT-styled examination for years.

Freshmen selected through wrong processes cannot live up to the stature of the claimed "echelon of highest academic excellence". Even though most DU courses are offered in English, all the classes are conducted in either Bangla or "Banglish", creating verbal communication deficiencies, which affect the students' acceptance in the job market.

Low relevance of tertiary education and skills training is also an issue of concern (World Bank, 2016). The 2012 World Bank Enterprise Skills Survey revealed that the graduates of Bangladesh's higher education and training programmes are inadequate for today's and tomorrow's labour markets.

DU took the country to roads not taken before and became symbolic to all the major movements that took place in the country since and before Bangladesh's inception. Though the university has fallen from its grace, it has not lost its relevance. The centenarian academic institution is still home to students from all social, racial, and economic backgrounds.

The first Vice-Chancellor of DU, Sir Philip Joseph Hartog, aptly remarked that the university that is content with its past is half-dead. The DU admission authority and think tanks need to re-fashion their admission strategies and testing methods. However, the reform process, for sure, has to be backed by the policy regime, as DU cannot raise the standard of its question papers to the required level until and unless the dividing education system of the country is overhauled.

The writer is an independent researcher and a former student of the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments