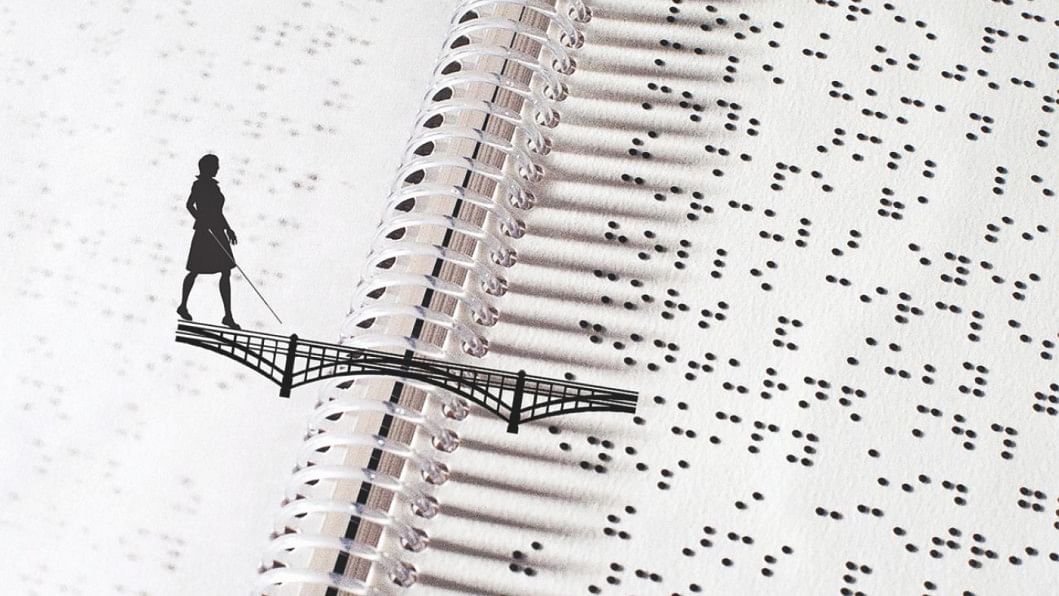

Search for sight and community in Sydney

Growing up, I was always told to be prepared when embarking on something new. Sometimes, however, there is very little one can do to prepare for the bumps along the journey we call life. That is what unfolded after I was accepted to a leading Australian university as a PhD student. I believed that it would be fairly smooth sailing both academically and socially as I had lived and studied overseas before. I was in for a rude shock.

In late August 2015, my plane landed at Sydney Airport, where I was greeted by an old high school friend from Bangladesh. As we travelled by train towards her home, somehow, it all felt unfamiliar and—I was in the 'West' again after a long time and Sydney just did not seem like the cities I had once known.

Before university started, I would be home alone and was reluctant to venture outdoors, because I am visually challenged (near-sighted). I was scared even to cross the street unassisted. Back home my parents did the most essential things for me—like going to shops and banking errands—or they would at least accompany me. I do not blame them as they did it out of concern but it did not help me in the long run.

At times, I would ask myself what possessed me to come here. I could not see beyond the difficulties. I realised that I should have practised doing things on my own well before leaving home, and that is a message of value I can pass along to young people going out into the world.

When it was time for me to start looking for housing, I found that properties were either too unhygienic, the rent too high, or they simply were not to my liking. One landlord actually told me that I could only cook boiled food!

Meanwhile, university started and that is when all the real problems began. With low vision, I required certain assistance related to my studies. These included getting access to eBooks and reading software. One would be surprised, but my university did not have adequate facilities to meet my needs. Apparently, this university had one of the better disability units in the country but it would take four months for them to figure out ways to help.

My disability advisor said one day: "We were not ready for someone like you." However, blind students studied here too and required more. I was literally shuffled from one authority to another. I felt overwhelmed.

I would not get my books, which often had to be transformed into electronic copies, on time. Although the disability unit and library staff soon started assisting me, my disability advisor behaved indifferently. One former blind student who I met later admitted that she left the university because of lack of support.

It would not be long before I met Antoni from Indonesia, who was pursuing a PhD and had been in a wheelchair all his life. I confided in him about my troubles and how unapproachable my disability advisor was. He told me that he had received similar treatment and referred me to two faculty members who had worked on disability issues. I contacted Professor Fisher and he reassured me that things were going to be alright and referred me to the second faculty. I remember Dr. Smedley with great affection because I would not have coped without the assistance and guidance this kind soul gave me.

My growing circle of friends taught me to use an ATM machine, send money home, and do online banking. Based on my experience, I strongly believe that there should be an induction programme for even international higher degree research students, especially those with disabilities.

Then there were the cultural hurdles. In Australia, the culture is individualistic, whereas I had come from one that placed greater stress on community, so people seemed unfriendly at first. My PhD colleagues were naturally interested in discussing thesis topics and asked me about mine, which was fine but I found myself repeating that conversation a lot... even at lunchtime! I felt that they were too focused on academics while wondering why they were not interested in getting to know me. Furthermore, at this level, many students had families and were unable to spend time with me. I found myself feeling very out of place. I started seeing a counsellor and took anti-depressants and that may well have saved my life at the time.

After a month at a friend's place, I moved into a shared house with Chinese students who initially were unsocial and spent most of their time in their rooms.

It started turning around after six months, when I moved into a residential college on campus. Among students from all over the world, I was made to feel welcome there and we ate our meals together. Hanging from the ceiling of the dining hall were flags of the countries that the residents hailed from. At long last, I felt like a part of a community.

As time went on, I worked hard on my research and made more friends. I met Bangladeshi families who became my companions. We would visit the pristine beaches of Sydney. Furthermore, I started doing things on my own. I was 'mobile' for the first time in my life thanks to the kindness of my Mobility Trainer, Margret, from a wonderful charity organisation called Vision Australia.

The crippling struggles I faced initially and my eventual deliverance have taught me lessons I will never forget, and I know that now I will be better prepared.

Tahreen Ahmed is an Educator by profession who has taught English at the Tertiary level for several years. She has an M.Phil in English Language Education. Tahreen was born with Congenital Nystagous (nearsightedness).

Comments