Sexual abuse at the hands of UN peacekeepers

In November 2015, a 14-year-old girl in the Central African Republic (CAR) said that two peacekeepers attacked her in November as she was returning home near Bambari airport. Peacekeepers at the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) base were stationed there to guard the airport and allegedly committed numerous such acts of sexual abuse and exploitation.

She told Human Rights Watch: "The men were dressed in their military uniforms and had their guns. I walked by and suddenly one of them grabbed me by my arms and the other one ripped off my clothes. They pulled me into the tall grass and one held my arms while the other one pinned down my legs and raped me. The soldier holding my arms tried to hold my mouth, but I was still able to scream. Because of that they had to run away before the second soldier could rape me."

Earlier in 2015, a 29-year-old woman was forced to engage in sexual relations with MINUSCA peacekeepers in exchange for food and money. She said to the human rights organisation: "The conditions of life at the [displacement] camp were precarious. I did not know what to do so I started having sex with the international forces. For this they gave me fish, chicken, jam and bread. Sometimes they give me between 1,000 and 2,000 CFA (approximately $1.60 to $3.30 USD) Before [the conflict], things were not like this…. I had to make decisions because life was so difficult so I chose to enter into these relations for survival."

Over the past decade, such allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse of civilians by peacekeepers have overshadowed UN operations on missions worldwide. Widespread rape and sex in exchange for money, food or relief goods, including acts of sexual violence against young children, have occurred—with the highest number of allegations in the CAR, Haiti, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and South Sudan, among others. Previous abuse was reported in Cambodia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, East Timor and Liberia, among others, in the 1990s.But as the number and scale of missions grew, so has disturbing allegations against UN peacekeepers in recent years.

Between 2004 and 2016, the UN received almost 2,000 allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation, including 300 involving minors, as was uncovered by an Associated Press investigation, by its peacekeepers from Bangladesh, Brazil, Jordan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Uruguay and Sri Lanka, among others.

Worryingly, few led to prosecutions in their home countries and when these did land in court, led to reduced sentences. Of 134 Sri Lankan peacekeepers accused of exploiting children in a sex ring in Haiti between 2004 and 2007, 114 were repatriated but none served jail time.

How is Bangladesh implicated?

The latest data available by UN peacekeeping's conduct and discipline unit reveals four cases of sexual exploitation and abuse by Bangladeshi peacekeepers, which have been reported by the UN to Bangladesh. Of these, two of the accused peacekeepers were police personnel part of the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH)—one accused of transactional sex (investigation of which is pending) and the other of the sexual assault of two children in June 2017. The latter allegation was substantiated following which the peacekeeper's payments were suspended but final action remains pending.

The other two allegations involved military personnel, both of which were substantiated. One was of an exploitative sexual relationship between November 2015 and January 2016 that led to the victim bearing a child of the peacekeeper of the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO). A paternity claim was filed with the UN, and subsequently established. An investigation was conducted by the Bangladeshi military and payments withheld in the interim. A final sentence is pending.

The other involved the rape of a minor in CAR by two Bangladeshi peacekeepers part of MINUSCA in November 2015. The perpetrators were dismissed from the mission by the Bangladesh military and later sentenced to one year in jail each.

In a statement in January 2016 following revelations by the UN that perpetrators included Bangladeshi peacekeepers, then director of the public relations wing of the Armed Forces, Shahinul Islam, said a probe was underway and that "Bangladesh will follow a zero-tolerance policy if anyone [is] found guilty."

Naming and shaming

After years of inaction and misreporting of the extent of sexual abuse by its peacekeepers, the UN has finally begun disclosing the country of the alleged perpetrator, 2015 onwards, in a strategy of naming and shaming. A total of 865 perpetrators have been identified between 2010 and 2018. The largest number of alleged perpetrators are from South Africa, 28, and the DRC, 26, while Bangladesh falls on the lower end of the spectrum alongside Pakistan, 4, and Nepal, 3.

Researchers and human rights workers say sexual exploitation and abuse by UN peacekeepers is likely under reported; an independent investigation into the situation in Haiti estimated 564 victims where the UN counted only 75 allegations of abuse, between 2008 and 2015.

As noted by Hillary Margolis, women right's researcher at Human Rights Watch, following the documentation of cases of sexual exploitation and abuse in CAR in early 2016, there is something particularly heinous about peacekeepers, sent to protect civilians from the violence of armed groups in the country, turning out to be predators.

Peacekeepers are in war-torn and politically fragile spots of the world where the power dynamics are skewed in their favour. Even sexual relations between UN staff and locals in these countries were also prohibited, in a 2003 bulletin by then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, "since they are based on inherently unequal power dynamics, [and] undermine the credibility and integrity of the work of the United Nations."

What can the UN do?

The UN has no jurisdiction over peacekeepers; neither the UN nor the host country can prosecute crimes committed while on missions. What it can do is send accused peacekeepers back to their home countries and bar them from any further peacekeeping missions. The UN reports allegations to the country of the peacekeepers involved and investigation and prosecution of criminal cases, and if necessary, punishment, is left up to them.

Accountability for the victims in faraway countries is rare as the names of alleged perpetrators are kept confidential and few cases end up being prosecuted. They received little medical or financial assistance let alone any updates on case proceedings. Only recently, in March 2016, has a trust fund been set up for the victims by the UN Secretary-General but it has found few donors among member states. Now, payments withheld from peacekeepers against whom allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse have been substantiated are also transferred to the trust fund.

Transparency and non-cooperation are also problems. Troop-contributing countries often fail to update the UN on the outcome of investigations and disciplinary proceedings (if these are happening). Recently, the UN also announced six months as a deadline in which to conclude investigations or move on with prosecutions. Commanders are rarely held responsible for their troops' acts. The sentence is often grossly disproportionate to the severity of their crimes.

Only if the host country agrees, can the UN join the investigation. Otherwise, what the UN can do is bar a commander or a country from getting other peacekeeping contracts (much coveted in countries such as Bangladesh), if it is found its handling of sexual abuse allegations lacking. Even this is difficult as the case of CAR illustrates, where the UN was unable to repatriate a battalion accused of committing widespread sexual abuse because it simply does not have the peacekeepers to replace them in what it said was a delicate time for the country.

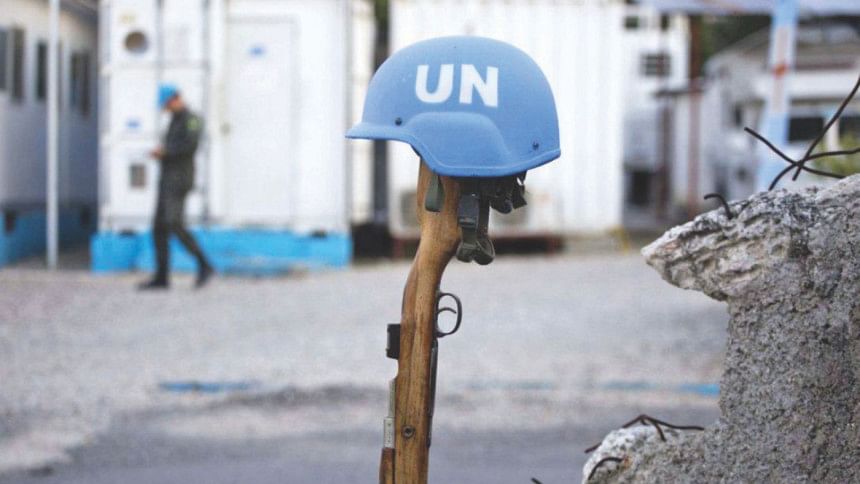

The UN has a zero-tolerance policy on sexual exploitation and abuse, introduced in 2005. Previous Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon called sexual exploitation and abuse "a cancer in our system". But fresh cases continue to appear and allegations persist in ongoing missions. For the blue helmets, whose mission it is to protect vulnerable civilians in conflict zones in the transition to peace, these allegations against them tarnish the reputation of the UN as a whole.

"Without accountability, people will continue to get away with this. These soldiers are put in a position where it's easy to perpetuate these crimes, and if they are not held responsible, and if their commanders are not held responsible, these crimes will continue," said Margolis to TIME in February 2016.

Bangladesh's investigations of its UN peacekeepers should follow through in a timely, transparent and accountable manner in order to avoid tainting its reputation in peacekeeping. Bangladesh's participation in UN missions is a great source of pride for the armed forces, a much-needed source of financial gain for underpaid troops and a boon to the country's image globally. It should not be overshadowed by the darker side of UN peacekeeping that has been exposed over the years.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments