WHY WOMEN POLICE DON'T REPORT SEXUAL VIOLENCE

When the 23-year-old constable Halima Begum was posted to her new workplace at Gouripur Thana, Mymensingh, her father, Helal Uddin Akand, was ecstatic.

"I was happy that she could come home frequently, as she was now 30 km away from our home in Purbadhala upazila in Netrokona District. But we couldn't have imagined, in our worst nightmare, that the posting which seemed like a blessing to us would result in my daughter's suicide," says Akand.

Halima poured kerosene all over her body and set herself on fire in her room at the barrack, on April2, 2017. She died on her way to Dhaka, while she was being transferred to Dhaka Medical College Hospital for better treatment.

However, before breathing her last, Halima left behind a statement to the police super of her thana, claiming that she been raped by sub-inspector Mizanul Islam of the same thana and that, in spite of being informed, Delwar Ahmed, officer-in-charge (OC) of the police station, did not take any action.

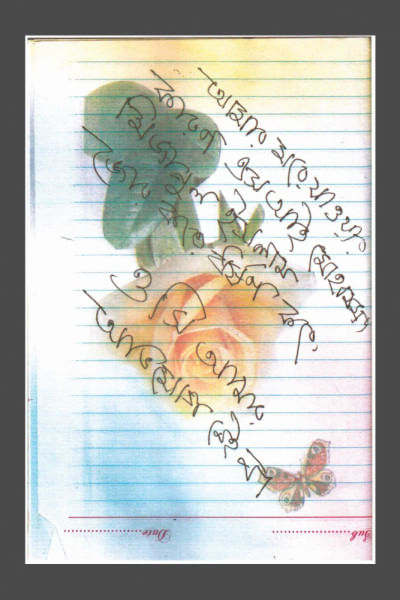

"It wasn't just her last statement. Five days after her death, when my family members and I went to the barrack to bring back her stuff, we found her diary in one of her bags, where she wrote down the same things," says Helal Uddin Akand, a freedom fighter.

"In fact, we found the written complaint she tried to submit to the OC, but which he refused to accept. It has details of how SI Mizan entered her room and raped her in the absence of her colleague on March 14, 2017," Iqbal Hasan Khan, Halima's maternal uncle tells The Star Weekend.

The written complaint also documented how SI Mizan raped her again on March 17, 2017, this time, using the pretext of a raid to catch a yaba dealer – a female yaba dealer – thus requiring Halima's help.

It also mentioned how another colleague—sub-inspector Ripon, who was informed about the matter, forbade her to file any formal notice. When contacted, the OC denied the allegation that he refused to take Halima's case and informed The Star Weekend that a week before that suicide, SI Mizan apparently made a complaint against Halima that she used to verbally mistreat him repeatedly.

"Apparently Halima used to be harsh with him and often hurled abuses," said the OC. According to Imarat Hossain, one of the investigation officers of this case, the accused SI Mizan has been taken to custody and the whole investigation might take one-two months to finish.

After Halima's death, many media portals were quick to come forth with theories about how she had a relationship with her rapist – as if that, in any way, minimises the severity of the crime. However, none of the media reports could provide an authentic source to such claims.

Halima's case is not a rare one. On October, 2016, a female police constable from Khulshi Thana of Chittagong was raped by her ex-husband, sub-inspector Sanjay Das of Rangunia Thana. A year before that, a female constable of Turag Thana was gang raped by her ex-husband, sub-inspector Kalimur Rahman of the Khilgaon Thana and his friends. However, many of these cases go unreported, regarded as "internal issues" of law enforcement authorities and kept, for the most part, confidential.

There is such a high tendency to hush the incidents of sexual violence within the police that, when a study of Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) revealed last November that at least 10 percent female constables, three percent female Assistant sub-inspectors and two percent sub-inspectors, are victims of sexual harassment, the police completely denied it. AKM Shahidul Haque, the Inspector General of Police (IGP) remarked that the data was totally baseless. He argued that no one can prove such statements and that there are no instances of sexual harassment of female cops (Prothom Alo, November 22, 2016).

Female cops we interviewed, however, share that they have to face sexual harassment at the workplace. Sexual violence does not always mean rape or physical violence; it may also be verbal or mental harassment. "In my six years, I have found many male colleagues who want to flirt with us about our outfits, appearance or sometimes very private issues," says a female constable on conditions of anonymity. "When it happened the first time, I spoke up and told them that I don't like such flirting, but then they started making fun of me, and within a few days, they made me feel like an outsider, isolated from everyone else," she adds.

When asked why she didn't report to her respective authority, she says that since it is a male-dominated force, the complaint may have resulted in more victimisation, with rumours being spread about her, or her being transferred to another station. Rather, one of her co-workers suggested that she ignore the issue.

Similar experiences were recounted by the participants of the CHRI's study. The study concluded that when a female police encounters sexual harassment, she does not report it thinking she would get punished, or her character will be attacked. As such, the offence gets normalised.

Fatema Begum, the first woman Additional Inspector General of Bangladesh Police and the first President of Bangladesh Police Women Network (BPWN), notes that it is really unfortunate that sexual harassment occurs in the police department. "But if anyone thinks that she would be victimised for making any complaints, she can make complaints to the BPWN. They have a helpline as well in this regard," she states.

However, The Star Weekend could not reach the helpline, even after trying for five days at a stretch.

Dr AFM Masum Rabbani, Addl. DIG (Special Crime) argues that sexual harassment of female cops are isolated incidents, and as such, "There is no need to generalise the problem." However, he adds, "BPWN has been working in this regard independently, and we have also formed complaint committee in all our police stations, as per the high court order. If we find any case regarding this, we always try to take prompt action."

If there is a serious offence like rape, the convict is usually dismissed from his job and tried as per the Women and Children Repression Prevention Act, 2000 informs Dr Rabbani. However, if it is a lesser offence in the eyes of the law, such as verbal sexual harassment, it is not necessarily handled as a criminal offence. There are three processes by which the perpetrator gets punished—rank reversion, dismissal from service, and forced retirement from the service. Meanwhile, if the allegation of sexual harassment cannot be proved, BPWN helps "manage" the situation by transferring the complainant or the accused to the various units of police.

Fawzia Khondker, who worked as a gender specialist on UNDP's Police Reform Programme (PRP), says that the PRP had drafted a gender policy for Bangladesh Police and submitted it to BPWN a year ago. "The gender policy insists on a zero tolerance on sexual violence, and if approved, would ensure that perpetrators are punished following the legal procedure. It is crucial that allegations of sexual violence are taken seriously by the police at all levels, and BPWN needs to more empower to take the necessary actions."

Had Halima received a prompt and gender sensitive response from her superior when she filed her complaint, she might still be alive. In order to ensure that no female police face a similar fate as Halima, the police, as an institution, needs to create an environment in which female police feel safe to raise complaints of sexual harassment, knowing that adequate action will be taken against her perpetrator. Unless we can end the culture of impunity of male police—and the corresponding silence of female police—we will not be able to foster such an environment.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments