Rampal Power Plant: Myths debunked

A timeline of the Rampal debate. Credit: Shaer Reaz and Amiya Halder

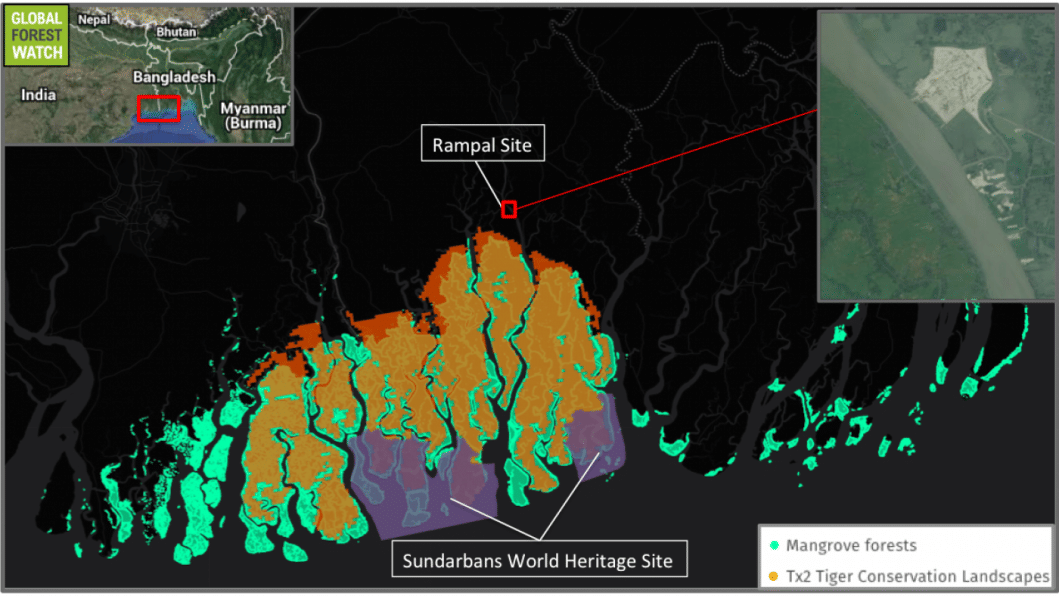

The construction of the 1,320MW coal-fired power plant at Rampal, near the Sundarbans, began last April. Hailed by proponents as a major step towards the development of the country and decried by protesters as a threat to the Sundarbans, its biodiversity and those whose livelihood depend on the forest, one would assume that a project such as this would result in engaging debate. One would be wrong.

From January 2013, when the Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the Bangladesh Power Development Board and the National Thermal Power Corporation Ltd, India (NTPC), the project has been mired in controversy. Land acquisition for the project started two years before an Environmental Impact Assessment was conducted. What followed over the course of the next four years has been relentless activism backed by experts on one hand and a constant demonisation of any dissent on the other. With facts and counter-facts pushed by both sides, one wonders how much truth has finally seeped through so that the average citizen can at least have an informed opinion about the issue, if not a choice.

The critics of Rampal include environmentalists, scientists and experts. Yet, the defence for the power plant has remained the same. But, under scrutiny, how do these claims, meant to relieve us of our fears about the potential risks of the power plant, hold?

Rampal is far enough from Sundarbans to be safe

A major narrative pushed by proponents of Rampal has been that the power plant being 14 km away from the Sundarbans is cause enough not to worry. But, is this far enough a distance for Rampal not to have ecological impacts on the forest and its biodiversity?

In 2013, environmental expert and professor of Environmental Science at Khulna University, Dr Abdullah Harun Chowdhury after conducting an independent EIA, found that the impacts of the power plant on the Sundarbans would be negative and irreversible. Pointing to his study on the impact of an oil spill in the Sundarbans in 2014, he says that due to that one single incident, the spilled oil had spread around 500 sq. km.

It has been said that emission from the power plant will not reach the Sundarbans since the wind generally flows against the direction of the forest. But, the official EIA acknowledges that "During November to February, prevailing wind flows towards South [towards the Sundarbans] and the rest of the year it flows mostly towards North. In most of the time of a year, emissions from the power plant shall not reach the Sundarbans except November to February." What happens during these three or four months is left unanswered. The EIA also mentions that emissions from the chimneys of the plant, containing harmful pollutants such as SOx, NOx, and mercury, will disperse at least 25 km from the source. This also counters the claim that a distance of 14 km will protect the forest from emissions, since according to the EIA itself, the emission can disperse to much greater distances.

A mission conducted in 2016 by the Unesco World Heritage Centre and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) raised similar concerns. The report of the mission stated that due to "the intrinsic connectivity between the property and the Sundarbans forest, it is recommended that the Rampal power plant project is cancelled and relocated to a more suitable location where it would not negatively impact the Sundarbans Reserved Forest and the property." It pointed towards the high likelihood of "contamination of the property and the surrounding Sundarbans forest from air and water pollution." Yet, the 14 km myth still persists.

Super duper technology means nothing to worry about

Ultra Super Critical Technology. Just the name sounds fancy enough to assure. The claim that Rampal will use Ultra Super Critical Technology (USCT) has been one of the most oft-repeated arguments to justify the power plant's construction. But what USCT actually is has seldom been made clear. In the simplest terms, it refers to the boiler which will be used to burn the coal and produce the energy. This claim raises two important questions.

Firstly, there remains confusion about whether USCT will actually be used in Rampal. Secondly, even if it were used, would it be a significant deterrent to pollution?

According to the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report (page 79) prepared by the government, Rampal will use Super Critical Technology (SCT). The tender documents, which are available on the Bangladesh Power Development Board website, also state the same. The EIA and tender documents have not been updated.

Dr Ranajit Sahu, a US-based expert, who has over two decades of experience in the fields of environmental, chemical and mechanical engineering including design and specification of pollution control equipment, in an interview with us, says: "It is not clear when it was decided that Ultra Super Critical Technology will be used. What is the meaning of changing the technology in the public documents if the tender document is not changed—since that is the critical document against which the engineering bidders will actually provide the technology?"

This brings us to our second issue: that even if Ultra Super Critical Technology was being used, would it be a justification for the construction of a coal-fired power plant near the Sundarbans? Here one needs to understand that the difference between SCT and USCT is in how efficiently they can burn coal. The project EIA claims that for each one percent improvement in efficiency, there will be 2-3 percent decrease in emissions since it would require burning 2-3 percent less coal to produce the same amount of electricity. Taking the efficiency of SCT (35 – 40 percent) and USCT (40 – 45 percent) into account, the reduction in pollution can be calculated to be 10 to 20 percent if USCT is used.

But, USCT cannot arrest the pollutants, which would still be emitted. The extent of pollution will largely depend on whether technology is being used to get maximum control over the emissions. Dr. Sahu points out, "regardless of the technology selected, the reduction in emissions will be modest if Ultra Super Critical is selected versus just Super Critical."

What emissions?

According to the the implementing body of Rampal Power Plant, BIFPCL (Bangladesh-India Friendship Power Company Limited), low-NOx burner technology will be used to arrest NOx emissions.

Dr. Ranajit Sahu, in reference to the the Environmental, Health, and Safety Guidelines International document of the World Bank/IFC, responds: "Typically, low-NOx burners (even advanced ones) will provide NOx reductions around 30-40 percent less as compared to standard burners. All modern SCRs [Selective Catalytic Reduction], on the other hand, typically reduce NOx by more than 90 percent. Thus, the NOx reductions (and environmental benefit) with SCR are much greater than just using advanced low NOx burners."

Similarly, the government is using Electrostatic Precipitator (ESP) instead of the latest Baghouse technology for controlling ash and mercury emissions. According to Dr. Sahu, most modern Baghouses are designed to achieve efficiencies much greater than 99.9 percent.

He also pointed out that once the coal is burned, most of the mercury in the coal is emitted in the gaseous form and only a small fraction in the particulate form. ESP technology cannot capture the gaseous mercury, while "baghouse, because of the way it works, will capture more of the mercury, including some of the gas phase mercury." Therefore, the claim that the latest technologies, which can significantly reduce the emission concerns, are being used in Rampal, fly in the face of these facts.

The fish are alright

It has also been claimed that there will be no negative effect on aquatic life due to the power plant.

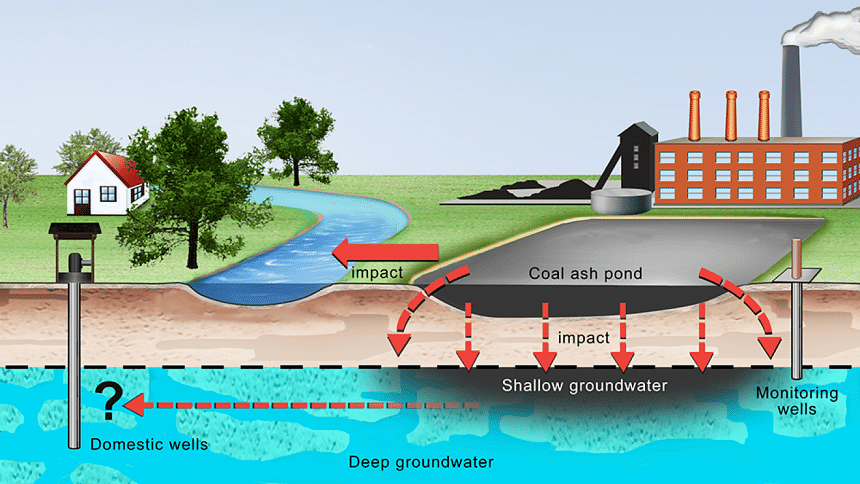

The plant will use 9,000 cubic metres [1 cubic metre = 1,000 litres] of water per hour and discharge 5,000 cubic metres of it per hour into the river. For this, the plant will continue to suck in more water to make up for the portion that is lost. This puts serious pressure on the quantity and quality of the already scarce water resource of the Pashur River.

A percentage of the water will be used to wash the ash produced from power generation into the wet coal ash pond. It will be contaminated by heavy metals because there is no water treatment system there. As per the EIA report, the ash would be initially stored in a 100-acre pond. Donna Lisenby of WaterAid warns that having an ash pond beside the Pashur River is like courting disaster. If the pond were flooded, the ash containing heavy metals such as lead, mercury, arsenic, chromium, and cadmium that are hazardous to human health and to wildlife, would spread throughout nearby areas and jeopardise the flora and fauna of the Sundarbans. Besides, groundwater would be contaminated if the heavy metals in the ash leach into groundwater due to any damage in the pond's lining, says the expert.

Again, the government says "temperature of discharge water shall never be more than two degree Centigrade above river water temperature at the edge of mixing zone which is as per stringent IFC norms".

But, Donna Lisenby has countered this claim, saying that the above-mentioned statement of the government is crafted to mislead people who do not know what a mixing zone is or how large they can be. Given the close proximity of the Sundarbans and the fact that any water pollution will flow downstream into the breeding area for rare and endangered aquatic life and badly affect them ["Bangladesh should not waste her scarce clean water resources in coal-fired power plants.", The Daily Star, June 11, 2015]

Covered ships equal no coal spillage

It has been claimed that because advanced, covered ships will be used to transport the 10,000 tonnes of coal which will be required daily by the plant, there will be no danger of spillages. But Bangladesh's track record, in terms of spillages and of salvage efforts, is far from laudable.

Since 2015, there have been three incidents of coal-spillage in the Sundarbans. The response from the authorities have been far from effective. How will the government guarantee that such spillages, which are more likely to occur once the plant is in operation, will not have disastrous effects on the forest?

The National Committee to Save the Sundarbans (NCSS) has also pointed out that in order to ship the coal to Rampal, extensive dredging operations will be needed so that the ships can reach the site. "Specifically, 26 km from the Bay of Bengal to the project site must be dredged, removing over 34 million cubic metres of river bottom that provides habitat for fish, crustaceans, and dolphins." These dredging operations would have to be redone every year to maintain access.

The EIA for Rampal admits that the environmental impacts of dredging the Pashur River and dumping of dredge spoil may increase turbidity of water, reduce fish catch, change fish habitat, migration, feeding, spawning, and diversity, and contaminate the river with spillage of oil, grease and effluent from dumping sites. Dredging may impact the dolphins of Pashur and Maidara rivers, and dredging and increased shipping without 'properly maintained regulations' may 'impact the Sundarbans ecosystem especially Royal Bengal tiger, deer, crocodile, dolphins, mangroves, etc.'" ("10 questions: authorities answers, counter response", The Daily Star, September 7, 2016).

Barapukuria worked out fine

"Normally, during combustion, the finer components of coal ash react with air and consequently generate different toxic substances such as CO2, SO2 and NO2 which is readily taken up by living beings so poses a possibility of rising environmental contamination with health risk around this power plant for present and future."

The Barapukuria coal-fired power plant has been used as an assurance. It has been claimed that even with its backdated subcritical technology, the plant does not have any adverse impact on the environment. But research studies clearly indicate to the possibility of "rising environmental contamination with health risk around the plant for present and future." [M. Farhad Howladar, Md. Raisul Islam, A study on physico-chemical properties and uses of coal ash of Barapukuria Coal Fired Thermal Power Plant, Dinajpur, for environmental sustainability (2016) 1(4):233–247].

The study found that fly ash generated from power plants has "noticeable negative impact on soil, water, air and so on, of environment." The blackish water of the nearby river Tilai shows the intensity of contamination due to the coal-fired power plant.

As Dr Ranajit Sahu further clarified, "we are not aware if many harmful emissions such as mercury and other toxics are being monitored near Barapukuria." The threat from these pollutants has not been clarified.

Barapukuria is a 250 MW plant of which one unit of 125 MW runs effectively. Rampal, with the capacity of 1,320 MW, is ten times bigger than Barapukuria and so its coal requirement is much greater. Though the area Barapukuria is not as environmentally sensitive, its negative consequences speak volumes about the ensuing danger of building a big coal-fired power plant near the Sundarbans.

Because of the threat that Rampal poses to the Sundarbans, it is imperative that the government's responses to its critics are well-substantiated. The debate cannot be mere repetition of the same claims, when facts to the contrary are being provided by experts and environmentalists alike. If the Rampal plant is environmentally sound, then the government should directly address the issues raised and clear the confusions caused by the contradictory claims about the technology to be used. The case for Rampal, if there is any, should be through a transparent fact-based debate, not through half-truths, and misleading facts and arguments.

The writers are members of the editorial department, The Daily Star.

Dr Ranajit Sahu, Dr Badrul Imam and Dr Abdullah Harun Chowdhury were consulted for this article.

Comments