An Island Unto Itself

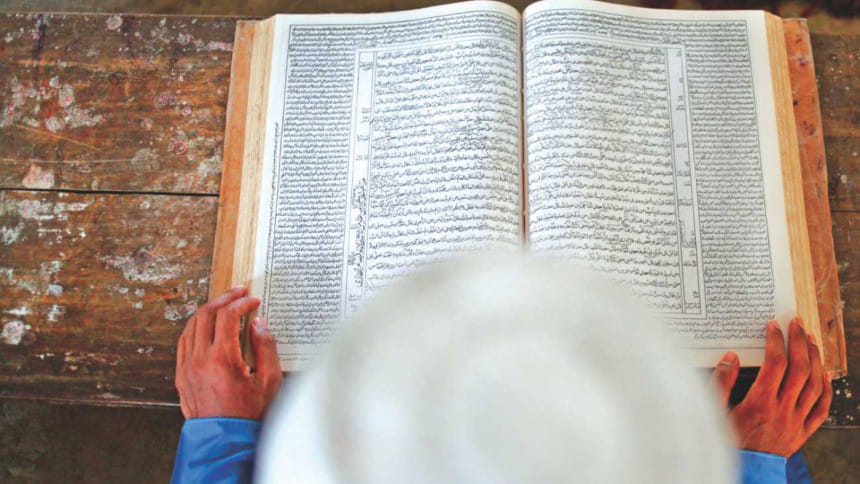

More than 1.4 million* students of Bangladesh study in an education system that has historically kept itself isolated from the rest of the world. In the strictly regulated residential environment of these institutions, students complete 20 years of rigorous study, only to have an uncertain career in the end. These graduates are absent from the corporate job market or the civil service, and the entire education system, which comprises of more than 14,000 institutions and a huge number of teachers and students, is totally excluded from the country's development plans and projects. These graduates are found in Bangladesh's mosques and madrasas where their only task is to teach, preach and pray.

They are the products of Bangladesh's Qwami madrasa-based education system whose academicians have adopted this extreme level of self-isolation apparently to protect the sanctity of Islamic education.

Initiatives to reform the Qwami madrasa have been rejected harshly over the years, and the system remains outside the purview of any government monitoring. When, on April 12, 2017 Bangladesh's Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina, recognised Dawrah-e-Hadith as equivalent to a Master's degree in Islamic studies and Arabic, criticisms and debates ensued. Questions were raised about how effective it would be to recognise the highest degree conferred by the Qwami madrasas without reforming and recognising the primary and secondary tiers of the system. It was also asked why the authorities of Qwami madrasa, who have long prevented any form of intervention, have welcomed this particular move of "mainstreaming" their tertiary education.

To understand the whole scenario, it is necessary to understand the entirely different pedagogic process practiced in Qwami madrasa. The education programme offered by a Qwami madrasa can be divided into six stages. These are: elementary stage, Ebtedayi; lower secondary stage, Mutawassitah; secondary stage, Sanabia Al Ammah; higher secondary stage, Sanabia Al Ulya; undergraduate stage, Marhalatul Fazilat; and post graduate stage, Marahalatul Taqmeel which is popularly known as Dawra-e-Hadith.

A bumpy beginning

From infant grade to grade five, a student of Ebtedayi stage mainly learns four languages—Bengali, English, Arabic and Urdu, with a special focus on the last two. In each grade, they have to study at least three books on Arabic and Urdu grammar and literature. In grade five, they also start to learn Persian language and elementary level Persian literature. In addition, they learn mathematics, history and social sciences. After completing class five, the students take a board exam which is controlled by the Qwami Madrasa Education Board (Befaqul Madarisil Arabia Bangladesh). However, unlike the mainstream education system, the students do not necessarily get admitted to grade six after they pass the Ebtedayi stage.

According to board officials, almost 90 percent of the Ebtedayi graduates get admitted to the Hifz course: an intense 4-5 year long course to memorise the entire Holy Quran. "We recommend that our students take the Hifz course because we believe that a student's intellectual capacity increases a lot after memorising the entire Holy Quran. He becomes more attentive; his patience and perseverance reaches a new level," argues Mufti Mehfuzul Haque, principal, Jamia Rahmania Arabia, which is one of the largest Qwami madrasas of Bangladesh.

Thus, by the time a student gets admitted to grade six, he has already spent around nine years in the madrasa. His counterparts in the mainstream educational institutions study in grade nine or 10 by that time.

In the world of Urdu, Arabic and Persian

From grade six to eight, which is called the Mutawassitah stage, a student is taught 11 books every year, most of which are on Urdu, Persian and Arabic literature and grammar. To complete this stage, every year a student has to sit at least four exams on Arabic grammar, two exams on Islamic law, two exams on Urdu grammar, two exams on Persian grammar and one on logic and philosophy. On the other hand, they take only one exam on Bengali and on English. Their Bengali and English textbooks, which are a condensed amalgam of grammar and literature, are published by the Qwami Madrasa Education Board.

For instance, in the Bengali literature textbooks of grade one, two and three, titled Shahittya Saogat, only 10 pieces of prose and 10 poems were included—none of which were written by a non-Muslim writer. The grammar section of the book is very brief and includes only a few chapters on sentence construction, verb and tense. The history and social science books of different grades reflect very little of Bangladesh's history and culture. For example, in the history book of grade four, there is a chapter on the birth of India and Pakistan but there is no chapter about Bangladesh's liberation. There is not even a line about Bangladesh in the chapter which discusses the history of emergence of India and Pakistan.

The importance of subjects such as Bangla, English, history, geography, mathematics and general science gradually decreases as the students move to the upper grades. For instance, after completing grade six, a student has to take a 100 marks exam on math but after completing grade eight, the student sits for a 50 marks maths exam. Again, general science is considered an optional subject in the curriculum. Geography and history are taught as half courses, which are concluded with a 50 marks exam.

According to madrasa teachers, they emphasise that students learn Urdu, Arabic and Persian as most of the Islamic books are written in these languages. As students are promoted to upper grades, they gradually remove mainstream subjects from their syllabi. In the secondary and higher secondary stages (from grade 9 to 12) their focus on Islamic sharia and philosophy intensifies greatly. When these students take the board exams after completing the secondary stage, they only sit for a 100 marks exam in Bengali and in English. And, in higher secondary stage they do not study any other subject except Islamic sharia and Islamic philosophy and literature.

Uncertain access to universities

These students cannot get enrolled in any public university of Bangladesh after completing their higher secondary education, as the public universities require passing 200 marks exams each in Bengali and English in the secondary and higher secondary level board exams.

Due to such discrepancies, if students of Qwami madrasa want to study in a public university, they have to take the Secondary and Higher Secondary School Certificate/Dakhil and Alim/ O and A level exams again as private candidates.

Omar Faruque who completed Dawra-e-Hadith course and is now studying at Department of Political Science, University of Dhaka, shares his experience: "Most of the Qwami madrasa teachers do not permit their students to take public exams like SSC and HSC while studying in the madrasas. Therefore if a student has to take the exam s/he has to leave madrasa early or they can take the exams after completing Dawra-e-Hadith as I have done which is a very lengthy and complicated process."

Mufti Haque defends this system by asserting that the goal of this education system is to create a pool of Islamic scholars, who will be able to provide religious solutions, not university graduates, doctors or engineers. "If we standardise our secondary and higher secondary level education and board exams with the regular education system, our students might leave the Madrasa to study in the universities or to get a job after higher secondary stage and we will get a few students in our graduate and post graduate classes."

"So, we don't want equivalency recognition for the lower tiers of our education system," he asserts. However, he stated that all the teachers and students welcome the government's recognition of Dawra-e-Haidth certificate as it will increase their opportunity in the national and global job market particularly in the Middle Eastern and North African countries.

As a consequence, a student of Qwami madrasa, who wants to continue his/her education, has no option but to get enrolled in a 2-year Marhalatul Fazilat programme, which Qwami Madrasa Education Board considers equivalent to a Bachelor's degree. After completing this programme, students are promoted to another 2-year-long course called Marhalatut Taqmeel, in which they study all the hadith books elaborately. Completing this course marks the culmination of formal education in a Qwami Madrasa.

Shortcomings of the system

The government's recognition of Dawra-e-Hadith under Qwami Madrasa Education Board as equivalent to Master's degree in Islamic Studies and Arabic has been welcomed by the madrasa teachers as it would apparently appease their students' aspirations without reforming the existing structure of their education system. However, for this very reason this decision has been criticised as the recognition came without addressing the existing discrepancies between Qwami Madrasa based and mainstream education system.

Although Qwami Madrasa Education Board has recently revised its curriculum, according to the experts, the revisions are far from enough. Dr Md Azharul Islam, professor, Institute of Education and Research, University of Dhaka, states that Bengali, English, Science and Bangladesh Studies should be incorporated more elaborately into the curriculum. "For Islamic education the teachers of Qwami madrasa can obviously teach Urdu, Persian and Arabic languages and literature but they should also teach those essential subjects with equal importance so that the students can participate in the country's job market after completing their education," he states.

Former students of Qwami madrasas also highlights that Mathematics and Science were taught very poorly in their institutions. Abdul Mubin, a Dawra-e-Hadith graduate now studying at Institute of Education and Research, University of Dhaka says, "Mathematics was quite an ignored subject in our madrasa. We learned only geometry and some elementary level algebra. Our teachers did not allow us to study arithmetic, as that section had problems related to the monthly rate of interest, which is haram (forbidden) in Islam."

However, he stated that he is required to have sound knowledge on secondary and higher secondary level mathematics and science to prepare for any job or even complete some of his courses in the university. As such, he is struggling with his courses.

"Before the Science exam, the teacher used to instruct us to memorise some question-answers. Science was like an optional subject," shares Abdul.

On the other hand, ICT education, which has been made compulsory in every tier of Bangladesh's regular education, is totally absent from the Qwami curriculum. Some madrasas have been providing ICT education on their own initiative, but they are not required to provide it, as the curriculum makes no mention of it.

The opportunity of co-curricular education is also very scarce in a Qwami madrasa, according to its students. In fact, the curriculum says nothing about co-curricular activities. Omar Faruque, a former student of Qwami madrasa now studying at the Department of Political Science in University of Dhaka, says, "There is hardly any organised co-curricular activity in Qwami madrasas. They do not participate in any national or inter-institution sports competition."

"In fact, most of these students have little idea about the outside world as they are prohibited from reading any book that is not included in the syllabus; they are prohibited from talking to people without permission from their teachers, " adds Faruq.

As a result, when these students leave the madrasa, they find it very difficult to compete for a job or to get admitted to a mainstream educational institution. "Ultimately, most of these students find the shelter of their familiar environment by working as a teacher in another madrasa or as an employee or imam of a mosque," comments Faruque.

Professor Serajul Islam Chowdhury states that isolating such a huge part of our population can be self destructive for the nation. "Through this education system these students acquire knowledge which they cannot apply to participate in mainstream economic activities. However, since they are focusing on religion in their studies, it creates a sense of pride and unity among them, which turns them into a social or even political force," he states.

Prof. Chowdhury adds that since they are isolated from our culture and society, the nation will find it difficult to accommodate their socio-political demands, which may be very radical. "The prospect of radicalisation through such an isolated education system is alarming for the stability and progress of a nation. In this regard, there is no alternative to revising the entire curriculum and teaching learning process of Qwami madrasas," he argues.

Recognition, why not reformation?

Dr Islam suggests that revision of the curriculum by incorporating Bengali, English, Science, ICT and Bangladesh Studies is very important so that these students can better understand the context of their own country and apply their knowledge in a more productive manner.

Furthermore, to implement this reform, Qwami madrasa teachers should be trained adequately," says Dr Azhar. Highlighting that there are no formal training facilities for the teachers of Qwami madrasas, he states, "Usually Qwami madrasas recruit teachers from madrasa graduates. They should be given training on modern teaching methodologies. And, for teaching subjects like Bengali, English and Sciences, they should recruit teachers who have Bachelor's degree on these subjects. Likewise, these teachers should also be given orientation on the teaching-learning environment of a Qwami madrasa."

According to Ali Riaz, professor and chair of the Department of Politics and Government, Illinois State University, USA, not only the curriculum and/or syllabi of Qwami madrasas should be a matter of discussion, but the environment of these institutions, the quality of teaching, and above all, the goal of Qwami education should also be examined.

"The necessity to integrate the Qwami madrasas into mainstream education cannot be disregarded. But how does the recognition of Taqmil or Dawra-e-Hadith degree address all students' needs?" he asks, arguing that recognising Dawra-e-Haidth certificate without considering these issues is ineffective and a manifestation of the ruling party's political expediency.

"Those who are in the other stages of Qwami madrasas will not benefit at all. This argument implies that all of those who are in the Qwami stream of education must attain post-graduate degrees to get any recogntion of their education," he adds.

Recognition comes with responsibility and now the academicians must bring about the necessary reforms which can turn millions of Qwami graduates into skilled manpower as well as religious scholars. However, neither the government, nor the teachers of these institutions are discussing these reform issues.

References:

*Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics, 2015

**The article is based upon an analysis of the academic curriculum published by Befaqul Madarisil Arabia Bangladesh

The writer can be contacted at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments