Dear university, are you listening?

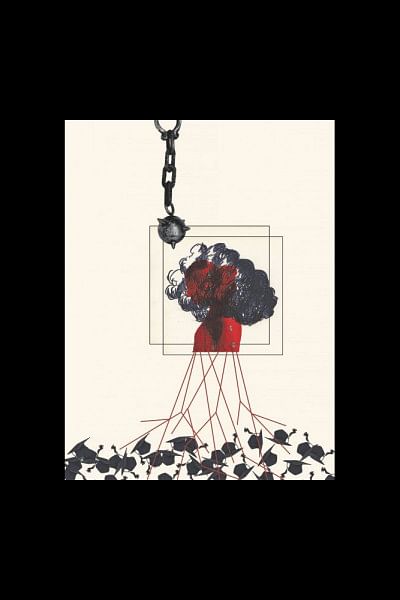

On November 20, an undergraduate student of BRAC University (BRACU) lost his life in the university's residential campus, referred to by students as TARC, in Savar—according to official accounts, he succumbed to his injuries on the way to the hospital after jumping from the fifth floor of his dormitory. The campus authorities and the police have both ruled that it was a case of suicide.

Beyond the "what-how-why" of the incident, this untimely and tragic death of a promising engineering student has also led many students and alumni of the esteemed university to ask a question that requires honest self-reflection: is their institution equipped to deal with mental health issues of the student body?

We do not know the details of the student's case(we are withholding the name to protect his family's wishes of privacy). What we do know, so far, from a statement provided by Rehan Ahmed, Campus Superintendent of BRACU's residential campus, to our Savar correspondent, is that the victim suffered from severe mental health issues—BRACU, he insists, was not fully aware of the severity of his condition, and that it did everything in its power to help the student once the university did find out.

When asked to clarify the extent to which the authorities knew and what steps they took to ensure his safety, Rajib Bhowmick, who heads the Media and External Relations section of BRAC's communications department stated: "Medical history is a strictly personal matter. We respect personal and family privacy and hence we are unable to comment on this."

On September 23, almost a month before his death, the student posted a Facebook status: "I am sorry to everyone whom I hurt directly or indirectly. I am guilty that's why god sent me to TARC. I am sorry to everyone." A few "haha" reacts to his post had led some of his classmates in the comment thread to speculate that he was being bullied. Was he, indeed, being bullied, and, if so, to what extent? Did the tutors, classmates, and counsellors manage to foster an environment conducive to the functioning and development of a student who was considered "different" from the pack? These are questions that, at this point, only the BRAC authorities and the student body can answer (the media, after all, has been denied access to the campus).

His classmate Mohammad Sakib Rummat informed Star Weekend that he was very "homesick". "He was childlike in some ways—all he wanted was his own home, own room, own computer and mom's cooking." Was he bullied, I ask. "A bit," replies Sakib,"But mostly, he was really unhappy about being here."

It should be mentioned here that the three-month residential semester at BRACU's Savar campus is mandatory for all its students, no matter their mental condition. A former BRACU student, Nusrat Jahan*, says that she had to drop out from the institution because the authorities wouldn't allow her to skip the residential semester—even though her psychiatrist had clearly stated that it would be detrimental for her mental health to be separated from her family. "My parents, my psychiatrist, and I all tried to explain that it wasn't a matter of 'not wanting to go away', but a real concern for my health and safety. But I was told that the policy was set in place and there was no room for exceptions."

Shami Suhrid, Psychosocial Counsellor, Lecturer and Coordinator, Counselling Unit, BRACU, confirms there is no other way for students to make up for the credits if they do not attend the residential semester. "But we try to make participation flexible. In special cases, upon written approval/permission from guardians, a student may choose at what point of their four-year graduation time they want to take the residential semester."

Nusrat, however, says that she and her family were unsure if she would be in a better position, emotionally and mentally, to fulfil this requirement down the line. "I asked BRACU if I would be able to transfer my credits if, say, in my fourth year, I was still unable to live on my own. They said it wouldn't be possible. I couldn't take the risk of losing two years of my academic life, so I had to transfer to another university," she explains. "It's a pity that I had to leave; I was thoroughly enjoying my classes at BRACU, and had a good GPA."

Other current and former students who suffer from mental health issues interviewed by Star Weekend state that unlike many students who enjoy their time at the residential campus, they felt alienated and their conditions worsened in the three months they were there. Some say they were bullied, and dorm tutors and counsellors provided insufficient support, often conflating their depression with "sadness" or "homesickness".

"I've had severe depression and anxiety since my teens, and it is difficult for me to engage with big groups of people. I feel overwhelmed and need to take a break sometimes. My dorm tutor would keep on telling me to 'go hang out with others'—she was completely unable to understand what I was going through. Even the counsellors had a rudimentary understanding of mental health services," says Rima Rahman*, a student of BRACU. "I am sure they had the best intention, it's just that they did not have the training or expertise required to deal with the kind of issues I had."

Another alumnus who attended the residential semester a few years ago says that her mental condition deteriorated dramatically during the term. Following a traumatic incident of harassment on campus, she shut herself down completely. She would miss classes and sleep during the whole day at a stretch, unable to confide about what had happened to her, even to the counsellors on campus.

"I was not in a position to seek help. Had I been with my family, they would have identified the irregularity in my behavioural patterns, and intervened earlier. Yes, I was asked to see a counsellor, and there was one who was welcoming, but I was afraid of telling her what had happened. I thought she might blame me, and in the end, the sessions didn't really help," says Hridita Ali*. "I would have emotional outbursts all the time, which made me a laughing stock amongst my peers, which further worsened my condition. Back then, I blamed myself, but now I understand that it was bullying. Perhaps we were too young, only in our second semesters, to be empathetic towards people who were different than us."

She completed the semester, but her condition deteriorated to such an extent that she had to take a break from her studies for two years. "It has taken me so long to recover. Even now, when I look back at those three months, I shiver thinking about how low I had fallen. Some days I didn't think I would make it." Nandita Chowdhury*, who had been diagnosed with clinical depression and anxiety since her early teens, and on medication for the last few years, informs that she had to drop out of the residential semester in the first week, when her mother got very sick. "Even the doctors spoke to the authorities at TARC and asked them to let me come say goodbye to my mother in case something bad happens, but they wouldn't let me out. My anxiety shot through the roof, and I felt like I was going insane. My aunt came to TARC to get me and I decided I would just drop the semester and go back home." Even though Nandita only attended a week of classes, she had to pay the whole semester fee (BDT 1,30,000).

Discussions around and understanding of mental health is still limited in Bangladesh, and campuses, unfortunately, are no exception. To BRACU's credit, at the Dhaka campus, there is an active psychosocial counselling unit, comprising nine professional counsellors.

"If a student feels any kind of mental health related problem, they go and talk to the counsellors. Sometimes faculty members, peers, and guardians also refer students for counselling especially when there is any noticeable sign of decline in academic performance. The issues/challenges that the BRAC University Counselling Unit addresses include parenting concerns, academic concerns, adjustment issues, addiction, stress and burn out, goal setting, social and communication skills, etc.," explains Suhrid.

How does the university deal with students who are clinically diagnosed with depression or other mental health disorders? Suhrid answers, "BRACU does not have a psychiatrist, so we do not provide psychiatric clinical diagnosis. However, if any student or their guardians inform us that the student is seeing a psychiatrist and seek counselling support, the BRAC University Counselling Unit provides counselling services in consultation with the student, the guardian, and the psychiatrist."

It appears that the institution relies on self-reporting to identify and assist those most at risk. But it is often difficult, if not impossible, for those struggling with their mental health to take the active step to reach out to counsellors, especially if and when they are contemplating self-harm and given the widespread stigma surrounding mental illness.

And the problem of insufficient attention to and support about mental health isn't only restricted to BRACU, as the second part of this cover story (in the next page) highlights. Universities across the country—and students too—ought to take this moment tore-evaluate how they can create a better support system, eliminate mental health stigma on their campus, and promote a pluralistic and tolerant environment that is conducive not just for some but for all. They must find a better mechanism to reach out to those at-risk. Mental health must become a priority for those who need support, and those who can at least lend their ears.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments