The Layoffs

On January 12, Jubayer walked to his factory with his fellow workers to find his name and face up on the walls of the factory. He has since been unable to enter the factory and terminated from work.

The names and photographs of hundreds of workers who had been temporarily suspended, were displayed prominently on the walls of the factory in Kathgora, Ashulia. Star Weekend spoke to six of its workers, all machine operators, who say they boycotted their work peacefully but have since been laid off.

AR Jeans Producer Ltd. filed cases against 312 of its workers for alleged looting (of laptops) and vandalism and beating up of factory officials. The factory, only two years old, lists European brands such as Pepe Jeans, Pull&Bear, and Bershka, on its website.

Workers have since fled their homes, having been harassed or in fear of harassment, by police. "For one month, I haven't been able to live at home or nearby. I have been staying at friends' homes or with relatives," says Jubayer, gesturing to where we sit, in his uncle's house where he has stayed among other places, in fear of being picked up.

One of the 62 named in the case by AR Jeans Producers Ltd. is 25-year-old Rubel, who worked as an operator. Including 200-250 more unnamed workers, they stand accused of beating up factory staff and vandalising furniture, machinery, and stealing laptops—worth a total of six lakh taka—on January 10. The case document also states that this also led to loss in production and shipments amounting to six crore taka. One of those accused is a female worker, currently in jail.

Protests against wage structure disparities

To back up a little, in December last year, Jubayer, Rubel and his fellow workers waged peaceful protest (as did other factories across Ashulia and Savar) by boycotting work sporadically between December 9 and 20.

Following the minimum wage rise, declared in September and effective from December, entry-level workers saw their monthly wage rise to Tk 8,000 from Tk 5,300. A new gazette was published in late November, declaring the new wage structure across grades. Following this, workers in higher pay grades took to the streets in December and January after seeing that their pay rise was less compared to entry level workers, i.e. their subordinates. According to labour leaders, a majority of garment workers, over 80 percent, are operators in these higher pay grades (three, four and five).

Garment workers demonstrated between January 6 and 16 demanding higher pay raises in Ashulia, Savar, Gazipur and in Dhaka city. One worker was killed and around 146 were injured in clashes in Savar, Ashulia and Gazipur with police, where rubber bullets and tear gas were fired. The demonstrations stopped once the government agreed to a revised pay structure. The Savar-Ashulia belt, on the outskirts of Dhaka, saw the worst of the protests.

Entry level workers' wages increased by Tk 2,700 in one go. On the other hand, more experienced workers such as Rubel, in pay grade three, received only a rise of a few hundred taka. "If the salary of your junior, the person you taught work, increases more than yours, would you accept it?" he asks rhetorically.

In January, peaceful boycott of work at AR Jeans continued after workers again received their wages and noticed that the disparity in pay they had been protesting against, had not been resolved by factory management. But, workers say they returned to their machines following assurances from their management that their higher wage demands would be met. But fearing attack from protesting workers on the streets who had taken issue with the fact that this factory was still running, these workers left early on the day of January 10.

"What guarantee was there of our safety? Inside the factory we are fine but who was going to provide security for us on the road home?" asks Jubayer. He and others workers emphasised that CCTV footage should be checked to see if workers caused any damage to factory property.

The events which then unfolded according to the workers differ from what the factory claims in the case against the workers. Rubel and Jubayer maintain that they simply left the factory that day without attacking anyone or vandalising factory property.

Five other workers of the same factory Star Weekend interviewed, claimed they had protested peacefully, boycotting work, in January when they wanted assurance of their pay rise.

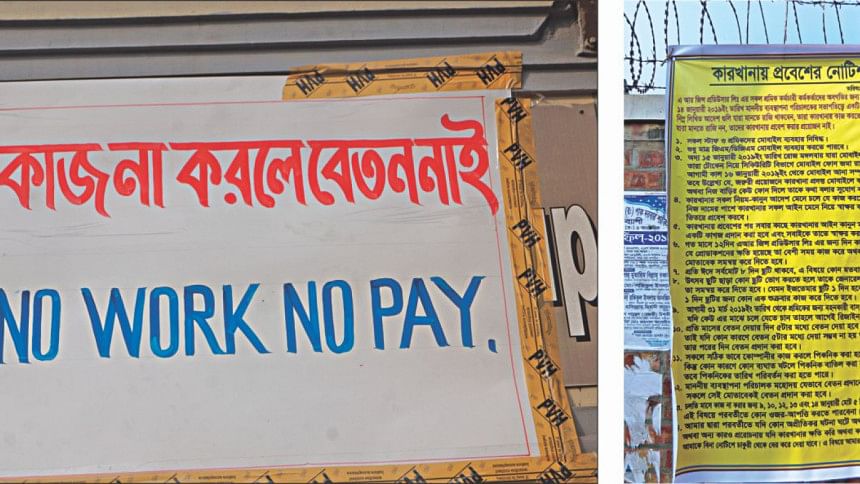

Following this, the factory was closed indefinitely, the gate bearing a closure notice and the "No work, no pay" for the workers, displayed prominently. The sign also cites article 13(1) of the labour law, which states that an employer may close down the factory "in the event of an illegal strike".

Their factory remained closed indefinitely between January 12 (the 11th was a Friday) and January 16. Rubel was warned on the morning the factory reopened, to stay away. Not only was his name up on a large banner on the factory walls but he had also been one of those named in a case against multiple workers by factory management.

Some workers say they have been targeted by the police. "Since December 18, I haven't been able to sleep at home for a week," says Rubel. Workers have been arrested from their houses and their factories in Ashulia, according to fellow workers and local labour leaders. One night, he says, around 50 of the workers slept in the open in the local bazaar with nowhere to go.

"I have received threatening calls from the police, starting from the day after I saw my name up on the factory wall sign. They keep asking me to go to the thana and threatened that even if I was underground, they would find me," says Jubayer. "The police went to my home, but I had warned my family ahead of time to give them a false location. The police went there too."

Incomplete or no severance

According to news reports, FNF Apparels, Al Gausia Garments, Knit Asia, Hollywood Garments and FGS Denim, AR Jeans Producers, Knit Asia among other factories have laid off hundreds of workers each. More than a thousand workers were fired from Abanti Colour Tex Ltd, in Narayanganj, alone.

Star Weekend spoke to 10 workers in factories around Ashulia who had recently been laid off following the early January protests in garments factories. The workers of AR Jeans received varying payouts, depending on the length they had worked at the factory. But, they say, this payment did not include the full benefits they know they're entitled to under the labour law.

The case of AR Jeans Producer workers, among others, is being handled by the Garments Workers Trade Union Centre (GWTUC). "Legally, if they completed six months at the factory, the workers are entitled to full termination benefits," says Joly Talukder, general secretary of GWTUC.

Following pressure from the union, the factory agreed to pay the workers on January 22. But, in keeping with what the workers stated, this did not comprise the full benefits they're entitled to. As per the labour law, workers are supposed to get a compensation of four months' wages, one month's salary for every year worked, and an encashment of their earned leaves in case of termination. "A case would mean a matter of long time and costs for workers, so they reluctantly agreed to take what the management offered at the time," says Talukder. They were essentially forced to settle.

An operator at Saybolt Textiles Ltd., who wishes to remain unidentified, says he was one of hundreds laid off from their factory, also in Ashulia. The workers stopped work on January 12 in protest of the arrest of one of their fellow workers in late December and two others the day before. In the same routine as AR Jeans Producer, the factory was closed for the next three days and when workers returned, they found a list of suspended workers on the gate.

After contacting their management through their union leaders, this worker and others were called for a negotiation with the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA). "We were told that if proven innocent, we would get our jobs back and get recompensed after two months. If not, we won't get anything except the salary of the 10 days of January that we worked," he says. Furthermore, suspended workers have not been able to enter the factory "I'm just a worker–I don't understand the law. And sitting around waiting for two months was impossible, as was being proved innocent. We have to pay rent."

After the negotiations, the workers went to collect the money at BGMEA Bhaban in late January. This worker we spoke to received a total of Tk 52, 732 (he had worked there for six years). "There was no breakdown, nor was it explained to us as was agreed in the negotiations."

Others have not even received any payout from their factory after being dismissed. Rupa, an operator in the finishing section at a factory of Dekko Group says she received nothing other than her wages for the month of January. A mother of two girls, she is currently unemployed.

Of the 10 workers we spoke to, only two workers had been able to find jobs after having been laid off mid-January.

Ataur says he has been able to obtain work at a nearby factory starting in February. Work is not difficult to find in these areas, where large microphones on a moving vehicle go around the area proclaiming that certain workers are needed in a certain factory the next day. But these workers fear giving their names when they go on interviews, in case they are identified as one of those laid off following the protests.

"I used an old card from a factory I worked at long ago," says Ataur. He says he had to resort to false pretences because he desperately needed work. Both he and his wife (also an operator) were laid off from their factories.

Another worker, Rezaul, says he lucked out because he wasn't asked which factory he had been at. He still lied and said he had worked at a different factory in Dhamrai. 25-year-old Liton, a supervisor at Hollywood Garments in Ashulia, has opted to look for work in Tongi as he has been unable to find work in Ashulia.

"I worked during the unrest as I was part of staff and not the workers boycotting. We didn't do anything, we even worked when no one was working, doing finishing." Along with hundreds of workers at the factory, he and other staff were fired. Liton received three months' basic salary plus wages for the 10 days he worked in January.

---

At the height of the protests, at least 5,000 of GWTUC workers' themselves had been laid off from around 25 factories. In total, says Talukder, the number is well above 7,000.

At least, 7,500 garment workers have been laid off according to Babul Akhter, head of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF). "5,845 workers have also been sued in 29 cases, where 515 workers have been named – among them 97 women."

"Our demands to the government and BGMEA are that workers innocent of vandalism and other charges brought against them not be harassed or laid off," says BGIWF's Akhter.

Siddiqur Rahman, president of BGMEA disputes this number saying the number of workers who have been laid off is around 3,000. But he maintains, any innocent worker, without evidence of wrongdoing, should not be harassed. "I have not received a single complaint so far where a factory has not complied with labour law [in these layoffs]."

"If anyone has not received severance benefits, they can come to BGMEA where we have an arbitration cell and these can be settled there."

"Everyone has to follow the labour law, workers too. If they have demands, there are several platforms to express it. They can take it up with the factory's owners, if there is a member of BGMEA or BKMEA they can complain there, there is a labour inspector at DIFE [Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments] where they can complain, and they can go to the labour court and ministry," says Rahman of BGMEA.

But as the workers have stated, they have been summarily dismissed without having the chance to prove their innocence. "Investigations are not happening and workers have simply been dismissed without their due wages. We have sent complaints to BGMEA and the labour ministry for five such factories where the workers have been summarily dismissed."

In order to lawfully dismiss a worker, he/she has to be given the chance to clear his name, and both worker and owner representatives together have to investigate, say labour leaders.

On an industry blacklist?

But even those unnamed/unidentified in cases have reasons to fear. They suspect that because their names and photographs were released publicly, they are on a blacklist by factories and the BGMEA. Their job search since being unceremoniously dismissed from work has not been easy.

"Right now, we are unable to find work," says Rubel, who says he was asked to leave at least five factories on giving his name, as he is one of those named in the case by his employer. "I won't be able to find work in group (big) factories anymore (because our names are known). I have to look for work in small factories out of BGMEA's purview," says Jubayer. They fear their list has been posted online and this is making it difficult for them to find a job anywhere.

"There is no scope for us to blacklist workers," says Rahman. "Workers should not be identified publicly, I have issued a circular that the factories are not to have the names and photos of workers printed and hung on the gates."

All the workers we spoke to said they protested peacefully. "I think I was fired because I had a history of reporting when I saw irregularities in the factory by staff," says the worker from Saybolt Textiles. Rubel at AR Jeans Producer says he and the other female worker were named in the case by their employer, because they were members of the factory's worker participation (PC) committee which takes up for workers.

"So far, have you seen workers' pay rise without us having to protest for it?" asks Rubel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments