Primary education in Bangladesh: All exams and no learning

Most of the time, however, one of her parents takes her to school and they carry her schoolbag for her. On the way to school, Rukhsana quickly falls asleep to recover from the sleep deprivation she suffers during the school week.

Her ordeal does not end here. In school, she has to attend physical training and fine arts classes, each, once a week. On those days, she has to carry extra books, notepads, and supplies. After her regular classes, Rukhsana has to attend three coaching classes conducted by her school teachers to prepare for the upcoming primary education completion (PEC) exam. She doesn't get any chance to play outside. She does not have the time to learn music, something she really wants. There are two music schools in her neighbourhood and she even got admitted to one last year during winter vacation. After two months, she had to leave because its schedule conflicted with her coaching classes. The only goal of young Rukhsana's life is to get a golden A+ (80 percent score in all the subjects) in the PEC exam.

Rukhsana is not the only child whose childhood is being destroyed in the race to obtain a golden A+ in the PEC exam. Rukhsana's mother, Sharmin Sultana, who works at an NGO, says, "All of her friends follow the same routine. They all study at the same coaching centre to prepare for the PEC exam. I know it creates pressure on her but if I didn't admit her there, she might lag behind her friends in terms of academic performance and results. She might feel left out or be frustrated as a result. Also, there is no secure playground in our neighbourhood where I can send my daughter. So, I try to keep her engaged in studies for as much time as possible."

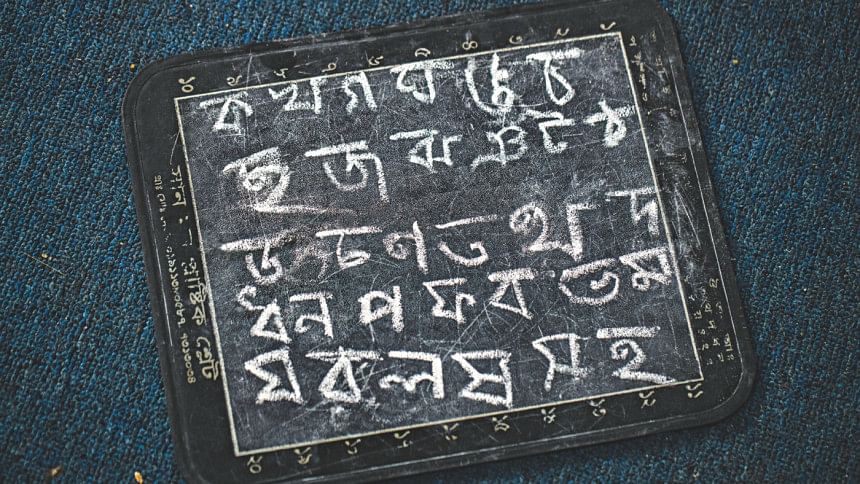

Rukhsana is one of almost three million children who sit for the PEC exam at the end of their primary schooling. However, this set of six exams, each two and half hours long, gives little to the students except a certificate. According to a World Bank report titled "World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education's Promise", 35 percent of our students cannot read Bangla comprehensively even after passing grade three. Only 25 percent of students achieve terminal competencies (a list of skills a student is expected to attain after completing primary education) and they lose four and a half years in the first 11 years of their schooling due to the poor quality of primary education.

PEC was introduced in 2009 and its madrasa equivalent, ebtedayi education completion (EEC) exam, was introduced in 2010 to ensure quality primary education for all. From the beginning, however, this move faced criticism by academicians and educationists. At that time, the draft of the National Education Policy 2010 was already completed. In this policy, primary education had been extended up to grade eight and all public exams up to this grade has been abolished. Despite these provisions, the PEC and EEC were introduced. According to Rasheda K Chowdhury, executive director of the Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE), "There is no country in the world where children of this age are being forced to sit for a public exam. The certificate they obtain through these exams do not add any value to their academic life. Instead, the psychological pressure the students have to go through is indescribable. They have to attend coaching centres, take preparatory tests, and solve guide books. The government wanted to ban coaching centres and guidebooks for the sake of quality education; however, this unnecessary exam has been making millions of students further dependent on guidebooks and coaching centres."

In the face of heavy criticism and the declining quality of primary education, the government took two initiatives in 2016 to reform the country's primary education system. One was to implement a core curriculum for all primary level institutions regardless of their medium of instruction, which would ensure that all young students would have a similar academic experience regardless of their socio-economic background. Another was to extend primary education up to grade eight which would reduce the burden of exams for students who have to appear in two public exams between grades one and eight and two more public exams before they pass higher secondary school. These two reforms were highly appreciated by all quarters.

Yet, the government postponed these initiatives up to 2021. "Since it has been mandated by the national education policy 2010 that primary education would be extended to grade eight, we will implement it anyway, today or tomorrow. However, we need to amend some laws. We are also short of infrastructure and trained teachers. This is why it will take some time to implement this decision," says Dr AFM Manzur Kadir, director general of the directorate of primary education (DPE).

Within three years of passing the PEC and EEC exams, students have to sit for another public exam at grade eight—the junior school certificate exam and for madrasa students, the junior dakhil certificate exam. According to academicians, such frequent public exams creates unhealthy pressure on students—many of whom drop out from school. "To prepare for the public exams, students are relying on coaching centres, guidebooks, and private tuition which are ultimately increasing the cost of education. The key reason for dropouts at the primary level are poverty and inaccessibility to educational services," says Professor Dr Siddiqur Rahman, former director of the Institute of Education and Research at the University of Dhaka and a member of the Kabir Chowdhury Education Commission that formulated the National Education Policy 2010.

"By making primary education more exam-centric and expensive, we are actually making our education system unaffordable and inaccessible to a large part of our population such as the disabled, ethnic minorities, the ultra-poor, and people who live in remote areas. Some of these children drop out during or immediately after completing the primary education cycle and sometimes they drop out before completing secondary and higher secondary levels of education," he adds.

According to the Primary Education Census 2018, 20.8 million students were enrolled from pre-primary to grade five in all types of primary schools. However, around

20 percent of these students did not sit for the PEC and EEC exams. In 2018, the rate of completing the primary education cycle was 81.40 percent. However, 37.81 percent of these students dropped out before completing their secondary education, says a 2018 report of the Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics.

What is the government thinking about this large number of students who are being deprived of their fundamental right to education?

"To reduce the dropout rate, we are trying to create a joyful environment in the schools. At present, we are providing more than 33,000 students of 175 primary schools with cooked food. By 2023, we aim to provide cooked food to all the schools of the country. Our study showed that school attendance increases by up to 11 percent if students are provided with cooked food whereas when supplied with only biscuits, the attendance rate increases up to six percent. We shall also provide each primary level student with Tk 2,000 for their uniform. When students will get new uniforms and nutritious and delicious food in their schools, they will feel more attached to their institutions," says Dr Kadir of the DPE.

Unfortunately, when these initiatives will be implemented is still uncertain. According to the DPE, these proposals are still on the drawing board. Once the draft proposals are finalised, these will be sent to the executive committee of the national economic council (ECNEC), and if approved, the DPE will then take steps to implement these.

However, experts have mixed opinion about these initiatives. According to Rasheda K Chowdhury, "There is no doubt that initiatives like these can decrease the dropout rate. However, there is a question of sustainability. For how long the government will be able to support these programmes remains a question. Also, chances are high that third party organisations can spoil these programmes. For instance, to prepare cooked food and provide uniforms, community-based organisations have to be engaged and they can seriously compromise quality for their own profit, ultimately spoiling the entire programme."

Chowdhury also emphasises how the government should reform the entire primary education system. "There is no alternative to implementing the National Education Policy 2010. If we can extend primary education to grade eight, we shall be able to transform this exam-centric education system into a dynamic, learner-centric one. Primary level students should not be assessed through public exams, rather they should be assessed through continuous academic performance. For this purpose, we need to overhaul the entire primary education system. We need to improve the classroom environment, train our teachers, and pay more attention to co-curricular activities."

Professor Dr Rahman focuses on decentralisation of the system as a way to reform primary education. "Including the last 20 percent of the population into mainstream education is one of the toughest challenges for a government. Among this 20 percent people are the disabled, the ultra-poor, people living in remote areas, children of ethnic minorities, sex-workers, Bede people, hijras etc. A way to include them is to form district budgets where special allocations are made to ensure education for locally marginalised groups. In addition, overall investment in education has to be increased so that more budget can be allocated to these pockets of deprivation," he says.

Unfortunately, even among South Asian countries, Bangladesh has the lowest budgetary allocation for the education sector. Although the National Education Policy 2010, considered the country's first comprehensive and modern education policy, has been formulated by the current government, most of its recommendations have not been implemented yet, particularly those related to the reformation of the primary education system. Further introduction of the PEC and JSC exams, defying the education policy, have pushed the students, parents and teachers into a rat race of getting A+ at any cost. As a result, more than 20 million children like Rukhsana are going through a torturous, joyless education system where they study just to get A+ but not to learn and progress.

Md Shahnawaz Khan Chandan can be contacted at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments