In Search of New Shades of the Human Condition

Photo: Kazi Tahsin Agaz Apurbo

When I first heard of the initial details coming out of the organizing committee of the third edition of Dhaka Art Summit, I felt a little perplexed. It is, after all, a very daunting task to go about presenting what is the world's largest South Asian art summit in a city that truly does suffer from a dearth of museum's and art galleries. No less intimidating was the fact that the summit was planning to showcase the work of about 300 artists and scholars who are either originally from or have worked very closely with the South Asian region, and on top of that the platform was to evolve from an exhibit of art to a space of research and exploration of not only art but the very real philosophical conundrums that are gripping the world today through written and spoken words and through film. But that is exactly the mandate with which the Dhaka Art Summit, produced by the Samdani Art Foundation, began on February 5 at the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy. The exhibition ran on till February 8 and attracted a staggeringly impressive number of viewers, patrons and participants.

To write about such a multi-faceted event, in itself, is no easy feat and runs the risk of becoming an incoherent mass of information and opinions. So, let us begin at the very centre of the summit- the art and the artists. Chief curator Diana Campbell Betancourt wrote in her opening message that the summit's aim was to address complex social, political and personal issues through a trans-regional narrative that aims to illuminate how the different nation-states, and the multiplicity of identities, languages and religions that it holds, exchanges and interacts with one another and the wider world. The exhibit begins on the ground floor and first floor with seventeen solo projects that asks us to think about our relationship with our land and the contingent and elastic movement of our bodies and identities amid the backdrop of a history of colonization from within and without and the infection of Western imperialism. So, was it successful? In many ways yes, and in some ways no.

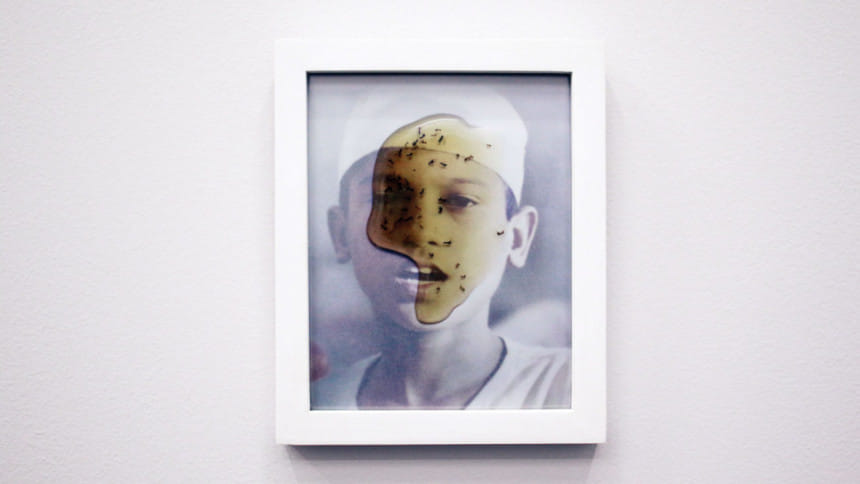

Credit must be given to Diana Betancourt's curation on the first floor and ground floor where complex solo projects were displayed in close proximity to one another, without ever giving the viewer the feeling that they were spilling over into each other. Some of the truly memorable displays include Mustafa Zaman's Lost Memory Eternalized where we are forced to look at images and narratives to a reconfigured lens of dead ants and honey. The viewer is disoriented from previously held imperialist notions to view the narrative of the historical other- the woman, the black children, the Hindu from the lower caste. Equally moving, but on entirely different wavelengths was Waqas Khan's presentation of The Text in Continuum, where his pen moves through traditional handmade wasli paper in an act of religious repetition, where the viewer is asked to observe the spaces where the artist breathes in, or breathes out, or moves slightly out of position. The artist's intended presentation of mysticism through careful observance is thoroughly successful. In terms of the statement provided at the beginning of the solo projects, however, the exhibit misses the mark. Too many of the complex and deeply emotive issues of the human condition centred around the image of the urban society. Although there was notable diversity of discourse through Munem Wasif's Land of Undefined Territory and Tun Win Aung and Wa Nuh's Ipso Facto, the concentration seemed to be the urban populace. Bangladesh is a country that is still trying to come to terms with its fledgling urban spaces- as are most of the countries in South Asia. At a place where the majority of lives and identities are shaped in rural spaces, the representation seemed lopsided.

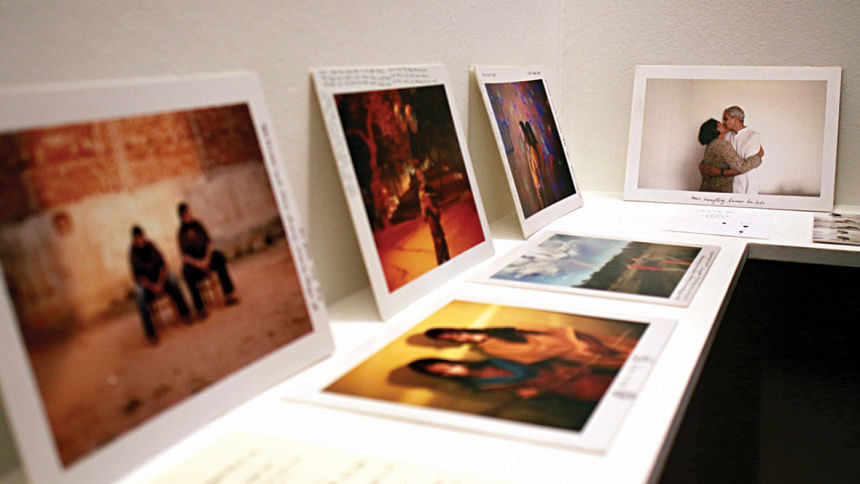

Apart from the solo projects, Soul Searching curated by Md. Muniruzzaman was the stand out exhibit, according to this writer. It captured more about Bangladesh than perhaps it even intended. As the fantastic folk artists grappled with our complex relationship with folk culture, performance artists such as Ali Asgar highlighted the very forefront of subcontinental (post)modernity. In a performance where the spectators could influence what he wore, the space brought forward important ideas about sexuality and gender expression. One of the big disappointments of the entire summit was the removal of Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam's Last Words, which showcased the final letters of Tibetan monks who self-immolated. We are well aware of the decades old occupation of Tibet by the Chinese government and to think that external politics was able to influence the display of art in what was meant to be a radically provoking space was extremely disappointing, to say the least. The exhibits Mining Warm Data and Missing One left a lot to desire, although the latter must be commended for its brave foray into the depths of modern art. The gallery Samdani Art Award displayed the works of Rasel Chowdhury, who won the 2016 Samdani Art Award. The gallery displayed works from a lot of Pathshala veterans and it was a good place to grasp the direction in which contemporary photography, in particular, is going in this country. Whether the summit could have benefitted from more Bangladeshi curators (Md. Muniruzzaman was the solitary one) is very much up for debate.

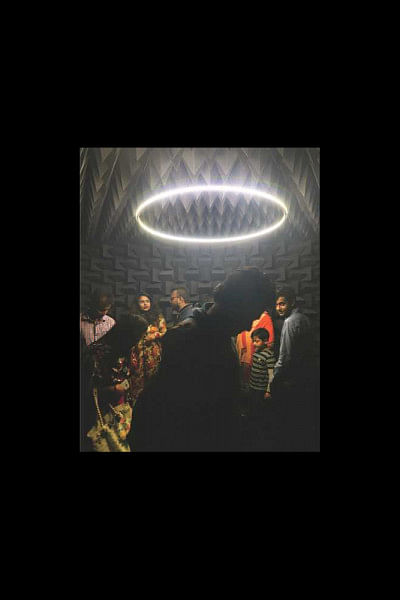

As mentioned earlier, the artworks were a part of a much larger platform. Talk shows and panels were held that discussed, very importantly, the philosophy behind the art and was a great place for evolving research. There was also a Creative Writing Ensemble and film screenings. But the summit could not have gained the unique character that it did without the throngs of people that came to visit. It felt as if a good part of Dhaka was there and it was truly encouraging to see people from all walks of life coming together to appreciate and understand art. However, there is a small caveat that this author would like to discuss. Among the scores that did show up, there was an exhorbitant amount of impatience that led into creating an atmosphere that would border on the chaotic sometimes. Sometimes there would be very little space to calmly comprehend an artwork or a performance, being surrounded by so much movement, chatter and the very disengaging trend of selfies. There were several instances where visitors would stand right in front of artwork in order to capture that perfect angle for what would no doubt be a scintillating selfie, leaving everyone around to sigh in frustration at their inability to view the art properly. The summit also hosted daily cultural concerts and dances and had a very impressive food court that really displayed a diversity of options, ranging from Sbarro pizza to the Chittagonian cuisine of Nawab Chatga.

In its concept, the Dhaka Art Summit is unique to our neck of the woods, and there must be deserved applause for Samdani Art Foundation for creating this platform for both artists and us lesser mortals who seek to appreciate and, perhaps, understand art. As an event it is still growing and improving over the years, just like our country itself, in certain moments fantastically brilliant and in others, a little incoherent. And perhaps nothing could be more symbolic than the fact that it is bound to leave a sense of ambiguous incompleteness, as all great art does. For the unfortunate ones who missed out, there is always next year.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments