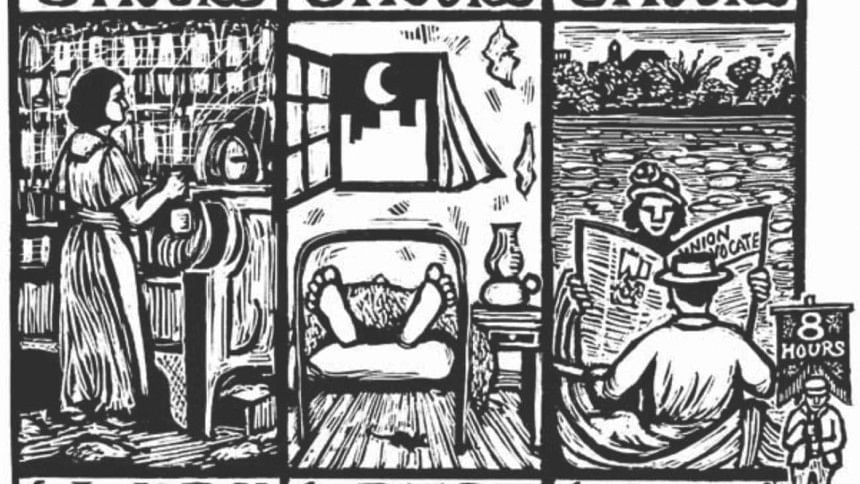

The myth of the 8-hour work day

Banu Begum, a 38-year-old garment worker, leaves home at 7.30 in the morning, drops off her two daughters at a nearby madrasa and then walks to her factory a few kilometres away. Work begins at 8 am; if she is late one day, Tk. 300 is deducted from her attendance bonus. From 8 am to 1 pm, she folds clothes at a stretch, standing on her feet. Her target per hour is to fold 80-100 shirts.

“There is no room for error. If I don't do it right the first time, I have to do it again, get scolded and lose valuable time. It gets so difficult sometimes, to do the same thing, over and over, and to stand for hours on end—my legs start giving in—but there is no rest,” says Banu. “If we go to the bathroom, we get a few minutes' break. That's all the rest our bodies are allowed.”

At 1 pm, she gets a lunch break for 30 minutes. General duty ends at 5 pm, but most days, Banu works till 8 pm.

“Some days, when demand is high, we work till 10 or even 12 pm,” informs Banu. “There's no break in between.”

On average, she works between 11–5 hours every day—that's excluding the household work she has to do for her family of four. She wakes up at 5.30 in the morning to prepare meals for the day, wash clothes and finish other household chores; she goes to bed around 1 or 2 am, depending on how much 'overtime' she has worked, after putting away dinner, washing the dishes and prepping for next days' meals.

When I ask her how she manages to survive with so little sleep and rest, she smiles wryly, and says, “What choice do I have?”

The concept of the eight-hour work day—a right guaranteed by our labour law and multiple ILO conventions—is not so much as lost on Banu, as circumscribed by the reality of her life. As per the law, RMG workers can work a maximum of two hours' overtime a day, with the average workweek not exceeding 56 hours. However, according to a study by the Workers' Rights Consortium, in Bangladesh, “workers report that an average workweek consists of 60 to 80 hours or more.”

As per another study by the Alternative Movement for Resources and Freedom (AMRF) and the Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC), garment workers work a minimum of 10 hours each day. As many as 39.5 percent of the workers reported working 13 hours a day or more.

There are widespread allegations by workers and labour rights activists that workers get paid an official wage—which includes their basic, other benefits and the legal overtime amount—and an unofficial overtime amount that is not recorded on their payslip or the paysheets that are presented to the auditors. For instance, Banu's payslip charts clearly what she received that month in wages and benefits in print. However, there is a hand-written amount at the bottom that exceeds her total income. There is no explanation of what this amount is. Banu claims that the hand-written amount is what she actually received that month and includes her overtime.

Banu's neighbour, Motia Akhter, who works at a nearby factory in Ashulia and overhears our conversation, eagerly chimes in. She explains that in her factory, things are done more “digitally”. Apparently, workers who work overtime must go back to the gate at 7 pm and punch their cards to signify the end of the working day for official records, only to go back to work till 9 pm or 10 pm. They sign a separate sheet afterwards, she says.

Workers further note that irregularities over payment of overtime, especially unrecorded overtime, is common. The study by the AMRF and the CCC, quoted above, supports this claim, highlighting that 54 percent of 243 respondents from different factories producing for the export market reported they had not been paid for their overtime. With little to no bargaining power in many of these factories, in the absence of a functioning pro-worker trade union, workers are forced to accept whatever amount they get.

The overtime they work is supposed to be voluntary, but when you ask workers if they have the freedom to “refuse” overtime, they laugh. For one, despite what the law states, overtime is considered mandatory in most factories, with supervisors, line-chiefs and managers frowning upon—if not castigating—requests to be let go early. For another, why would workers refuse overtime, when every extra hour worked means an extra few bucks to supplement their meagre salary?

Take Rahela Khatun, for instance. She lives in a small room in a house shared by six other families, with her two daughters. Tk. 3,500 – almost half her salary – goes towards paying the rent. She gives Tk 2000 to her elderly parents, and spends roughly Tk 1500 on her children, including Tk 800 as school fee. Another Tk 2000 – 3000 is spent on food.

“You tell me what that leaves me at the end of the month!” exclaims Rahela. “Some months, when my children are sick or my parents need more money or there is an emergency, I have to resort to borrowing from my sister or neighbours. This is why I work as much overtime as I can. If I don't work at least four hours overtime each day and some weekends, there is no way I can make ends meet.”

Given that the current minimum wage in Bangladesh the second lowest among the top ten apparel-exporting countries in the world (ILO 2014), it is no surprise that workers have to toil for hours on end, at the cost of their health and happiness, to just get by. Yet, demands for higher wages are met with resistance, albeit violence, from the owners and the state, as evidenced by the crackdown on labour in Ashulia last December. With the cost of living spiraling out of control with each passing year, workers have little choice but to learn to sustain themselves on 4 or 5 hours sleep a day, working non-stop for 12-14 hours. Recreation, and the promises of May Day and an eight-hour work day, remain, to them, but a distant dream.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments