Listening to refugees—lessons learnt from the past

In 2010, representatives of UNHCR came to Research Initiatives, Bangladesh (RIB) with the proposition to do some work in the camps engaging participatory processes. It took us a while to decide on what we would do if we were to take up the work. RIB was a research organisation specialising in participatory action research with marginalised communities but it had not previously worked with refugees nor had it worked in that particular geographical area where the camps were situated i.e. Ukhia and Teknaf in the Cox's Bazar district. So we responded that we were willing to work in the official refugee camps in principle but we needed to know more about that area and the people with whom we wished to work. Hence a 10-day scoping exercise was arranged, out of which five days were to be spent in the field. This was facilitated by UNHCR but it was up to us to determine the extent and content of the exercise. It was one of the most memorable visits— almost like a journey to the unknown—that my colleague Suraiya Begum and I had undertaken in our research careers.

It was a part of the country with which we had no exposure till then. Sure, many of us have dipped into the Bay of Bengal in the resort town of Cox's Bazar, but how much did we know of the people, their languages, the lie of the land, the weather elements which we had to encounter during our stay there? Our first task was to get a good local interpreter. We found Rashed Sorwar, at that time a young student of Cox's Bazar College, but who later along with Mobasherul Alam and Protit Mutsuddi became a steadfast colleague and stalwart friend.

Since we chose formally not to be part of the UNHCR ensemble as that may elicit a different kind of response, we did not have permission to enter the official camps. Instead we went to the makeshift site near Kutupalong camp where many undocumented Rohingyas had set up shacks and where refugees from camps also came to chat with us in one of the roadside tea-shops. We travelled as far as we could do by land to the "Land's End" point of Bangladesh known as Shah Porir Dwip. It was almost a mystical journey. As we crossed Teknaf, we came upon milestones which indicated the distance in a peculiar way: Shah Porir Dwip 4.15 km, 3.14 km and so on. My colleague Suraiya pointed it out and we wondered for a while. Then it occurred to us after the .15 km, that there was no more Bangladesh at least in terms of land; there was only the sea. We encountered too the thrill of seeing the mountains of Myanmar across the River Naf and across the jetty at Land's End. How near and yet how far! We took a surreptitious journey to the Ghumdhum border with the help of our friend Rashed where we encountered the high electrical fences of the land border with Myanmar and also the point where refugees were first sent back by the 1978 agreement.

In our travels we visited villages where we met with Rohingyas who had intermingled with the local population, those who chose not to say that they were Rohingyas, those who proudly displayed Bangladeshi voter's cards saying they have been here for many generations. Others said that they previously lived in Teknaf Bus Station or on the banks of the River Naf but came to the village where they were promised space to live on the land of a wealthy villager in exchange for guarding it. We also found local Bangladeshis who too have migrated to various parts of Cox's Bazar and Chittagong in search of food, livelihood and shelter. The words "floating poverty" came to my mind. It floated across the River Naf, it also floated along the coastal shores and tropical jungles of the south-eastern tip of our country hidden to the seasonal tourists who came to enjoy a getaway from the humdrum lives of the city.

"Mothers became concerned that their children were learning only Bengali alphabets, but what use would this be if at some point in their lives they returned to Myanmar as it was hoped that they would. We responded by adapting our system to the official Burmese alphabets as taught in schools in Myanmar.

But coming to the main objective of our visit: did we find a core point of interest in which we could anchor our work that would serve the needs of Rohingya refugees? We did, and it came from a most unexpected source.

Amidst torrential rains, we took refuge in a tea stall by the road side of the Kutupalong makeshift area. We started to talk with refugees who had come down from the official camps and makeshift settlements. It was an impromptu focus group discussion. The need for education for the refugee children came across strongly. But we knew that some muktabs were already in operation at the makeshift sites. So we asked if that was not sufficient for their needs. A young imam, himself a Rohingya, replied, "No, it is not sufficient. I can only give them religious training, but they need a more general schooling as given in mainstream schools, or they do not learn about real life." The statement took us by surprise coming as it did from a religious person. But others in the tea stall backed him up. They especially mentioned the traits of juvenile delinquency that often developed among youngsters in such situations and how early childhood learning could help them get the care that they often lacked as well as offer them coping mechanisms that could help their trauma and misery.

We came away with a budding idea. Research Initiatives, Bangladesh (RIB) had already in place 150 centres of the Kajoli Model of Community-Nurtured Early Childhood Learning for underprivileged children aged four to six. We thought of adapting it to the refugee camps as implementing partners of UNHCR.

Meeting the actual challenge of setting them up in the refugee camps was a task in itself. There was no extra space in the already overcrowded camps where we could set up the centres or build new centres. People told us it would be hard to convince refugees to send their young children to these centres if they don't get any direct benefits. Besides, refugees did not form a community and were often competitive in their claims for attention and benefits. To all these queries and warnings, we responded that we will be using the methodology of participatory action research, which would help us gain both the interest and participation of the refugees, and through their active participation and collaborative inquiry into the process, would give them a sense of ownership.

In a ground-breaking orientation meeting where we explained our model, we brought in prospective mothers, children as well as community leaders. There were already elected leaders in the camp, who were present but we also reached deep into the social structures of the Rohingyas themselves and invited persons who were generally respected by the people: school teachers, religious leaders, elderly women and men.

The demonstration of our model proved its popularity especially with children and mothers. But refugee leaders asked us despondently what this will do to change their actual situation as they all perceived that they had no future. I asked them whether they considered their children to be their future. They answered, yes. Then I asked, "Well then if your children are your future, and we are looking after your children, are we not looking after your future?" They gave their consent and we entered the camps.

But from the time of entry to our last days in the camp, challenges came one on top of the other. Some were situational like finding spaces for the centres, some ideological like how to consider the distribution of korbani meat among refugees or would women be allowed to participate in theatre workshops, and others, administrative like coping with restrictions imposed by officials. But all these were solved in collaboration with refugees themselves who were trained in the methodology of participatory action research by RIB. They also carried these processes into solving their problems at the level of the community, and family. Through such processes, they found space for the Kajoli centres in their own shelters, they decided that korbani meat would be distributed proportionately to poorer households, they repaired roads voluntarily to facilitate their children going to centres during the day as well as for the Ansars to patrol the camps at night.

Mothers became concerned that their children were learning only Bengali alphabets, but what use would this be if at some point in their lives they returned to Myanmar as it was hoped that they would. We responded by adapting our system to the official Burmese alphabets as taught in schools in Myanmar. They became ever grateful. "You listened to us, they said! Not many people do!" It was voices such as these that we wished to encourage because it is important to give back even in a miniscule way the sense of agency, dignity and ownership of their lives to people who have been robbed off it completely.

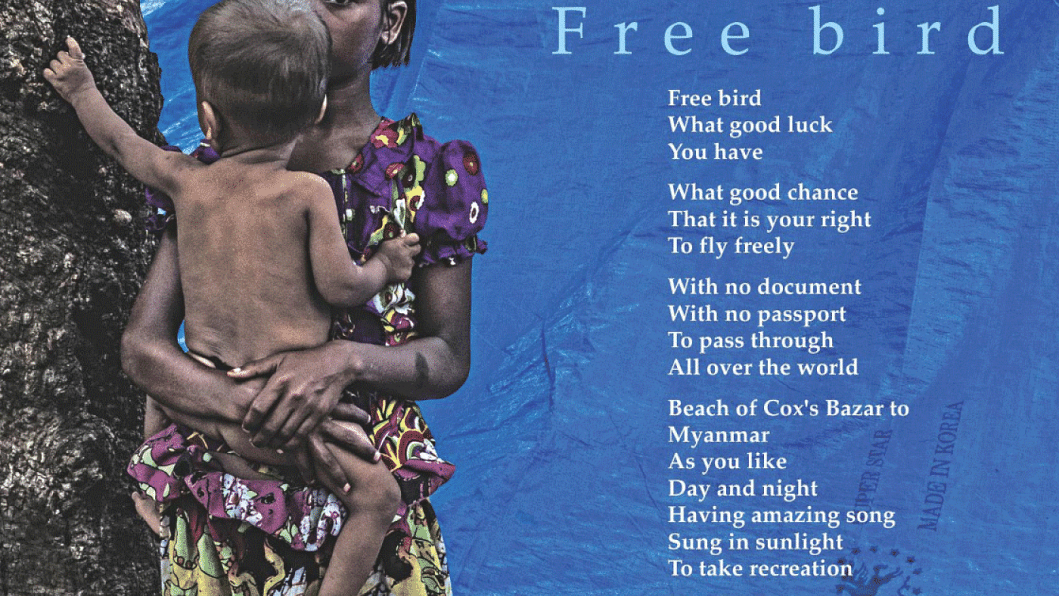

Now when we see the thousands of people fleeing into Bangladesh and most of them women and children and equally we see well-intentioned organisations rushing in with relief and emergency provisions, our first thoughts are to urge everyone to listen to what the refugees are saying, and not only to their traumas, but also to the sense of humanity and dignity that remains within them. For that is what should be protected, nurtured and restored. A poem, Free Bird, written by a young Rohingya refugee choosing to stay anonymous expresses this well (see above).

Meghna Guhathakurta is Executive Director, Research Initiatives, Bangladesh (RIB).

Comments