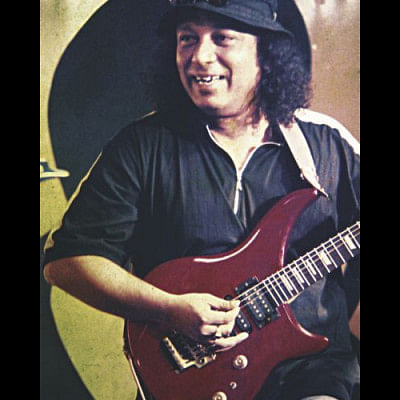

THE LAST RIFF

On October 18, Bangladesh lost one of its musical giants, the king of rock, Ayub Bachchu. His sudden demise left everyone reeling in shock, followed by an outpouring of tribute and love on social media, newspapers and TV channels. Much has already been written by his friends and followers about AB, the rock legend, and Bachchu bhai, the ever-so gracious Chittagonian. So we revisit, instead, the maestro on his own terms, in his own words, in an interview with Star Weekend (then the Star), published in November, 2012.

When you meet Ayub Bachchu off stage, it is easy enough to forget that he is a legendary rockstar. The signs are there, of course—in his all-black attire, the exclusive guitars that he fiddles with from time to time and the constant influx of different types of people hoping for an audience with the king of rock.

But beyond the obvious attention he commands wherever he goes—by virtue of who he is—there is very little about him that strikes as unusual. He is warm, humble and gracious, with a remarkable ability to make everyone around him feel welcome.

Even amidst the hectic launch of LRB's new album, Juddho, AB is the ever-affable host. "Have you been given your tea? Some snacks?" he asks us. "Will someone please make sure there are some sandwiches here?"

Bachchu admits that his fame, and the incredible love he has received from his countrymen, has humbled him over the years. "Every person deserves respect, no matter what their profession or background," he says, "I really believe that whole-heartedly and try to reflect that in my actions."

Ayub Bachchu is decidedly different—calmer, wiser and more responsible—from the young avid guitarist who left his familial home in Chittagong to pursue a career in music. "Thirty years ago, I didn't understand anything beyond myself and my guitar. I used to think that my guitar was my life, my career, my food, my air, my family, my friend … it was my everything," he says.

"But now I know that life is much more complicated. Every day, there are new challenges, new complications, new responsibilities. My two children are growing up and I have to think of their well-being," he states. "I have played the guitar for a long time but I often wonder what lies in my future?"

After an illustrious career in Bangladesh's music industry—an industry which he unarguably helped define—spanning almost three [now four] decades, AB finds himself wondering if it has all been worth it.

The son of Haji Mohammad Ishuque Chowdhury and Late Nurjahan Parvin, he grew up in the port city of Chittagong, in a joint family, surrounded by cousins, aunts and uncles. His family was like a big ship, he says, and he enjoyed the sharing and caring that was an inevitable outcome of being part of a joint family.

"I was, surprisingly, a good student, but my father wanted me to be even better, so he would change schools all the time when I was really young," he shares. "So back then, I made a lot of friends in different schools all over the city. I finally ended up in Muslim High School, where I was quite happy." As an adolescent boy, not unlike others his age, he would fly kites, play football with his classmates and dream of being a professional cricketer. "It seems amusing now, but I was really into cricket once," he says with a chuckle.

He started to dabble in music when he was in Class VIII. "We used to listen to cassettes back in those days. I would listen to one song thousands of times, rewinding and fast forwarding religiously, to accurately reproduce the music with my guitar," he says. "No one goes through that much trouble anymore—they can just download the songs and the tabs from the internet; now it's like a free-hand exercise." For Bachchu, however, it was the lengthy and difficult process of exploring and experimenting with different tracks to recreate the perfect sound that made learning more enjoyable. "It was a challenging process, and I loved it."

It was his father who bought him his first guitar—that, in a nutshell, was the beginning of the end. "It began innocently enough as a hobby, but at one point, I became very serious that I would have to do music. It became an obsession, and from that, a profession," he says.

His family staunchly resisted his decision, arguing that the entertainment business was no place for a son from a decent family. "In my family, most of them are haji. Initially, they simply couldn't accept that I would do music professionally. I don't really blame them. Back then, that path was really difficult for musicians. That path is difficult even now—artists can't be sure if they can survive solely by doing music," explains Bachchu.

When he first came to Dhaka, he couldn't afford to rent a house, so he stayed in a hotel in Elephant Road. He would try to avoid meeting the landlord, whenever he was low on cash to evade the rent. "If there was a gig, we could pay, and if not, we would have to owe the landlord for days. He was very nice though and understood our situation," reminiscences AB about his days as a struggling musician.

In 1978, he joined a band called Feelings, and then in 1980, Souls. Band music was a novel concept in Bangladesh at that time, but it was all AB wanted to do with his life. "From my childhood, I was fascinated by western bands like Deep Purple, Pink Floyd, Dire Straits and Led Zeppelin—I wanted to popularise that sound, that concept, among our audience," he recalls. "I've always wanted to be a guitar hero. Singing was never that important to me; guitar was always my first choice."

He spent a decade with the now-famous band, slowly coming into his own as a lead guitarist. After producing such memorable songs as Mon Shudhu Mon Chuyeche, Torey Putuler Moto Kore Shajiye, Eitoh Ekhane Brishti Bheja and Ek Jhaak Paakhi with Souls, he left to form his own band, LRB (originally Little River Band, later renamed to Love Runs Blind) in 1991.

"I left Souls because of different tastes in sound. I was into loud, rocking, powerful sounds, and the rest of the members wanted quiet, melodious sounds. You cannot compromise day after day. We never really had any big arguments, but it occurred to me that it would be better if I just quit and do something different," says Bachchu.

LRB is a hard rock band—always was, always will be, insists AB. Although musicians such as Zinga Goshty, Akhand Brothers and Azam Khan introduced and experimented with the concept of Bengali rock long before the band came into existence, LRB in the 90s played an instrumental role in shaping the genre's indelible image.

The audience loved LRB's first album—a double album, the first ever in Bangladesh. "There was so much fear and anticipation during our first release. We didn't know what we should do, what was happening," recalls Bachchu. "Later we found that people were actually waiting in lines outside some shops to buy our album."

There is nothing AB can't do, says his manager with quiet pride, and the truth of the statement becomes apparent when one considers the breadth and range of his work. Celebrated for his gritty blues-based lead guitar and considered by many as the best guitarist in the country, if not in all of Asia, AB is also a composer, singer, songwriter, producer, jingle-writer and recording artist.

"My sound has changed over the decades," says AB. "My target sound was a pure rock sound, not too refined, not polished, where the guitar distortion is clear. Thanks to technological advances and decades of experimentation, I am more or less settled in my sound."

Bachchu argues that his solo music is completely different from LRB's sound. He says, "LRB is complete hard rock, but the music I do myself is full of melodic and romantic songs. There is not much experimentation. Even if I want to, I can't be too experimental because my regular listeners don't appreciate it. They still prefer 'me-you' type love songs."

Bachchu experimented with two of his albums, Shomoy and Eka—infusing blues, jazz and funk elements into his usual style. Lyrically, too, he wanted to break out of the 'me-you' tradition of soft romantic songs. "But they were not received well at all. My regular audience thought it was too high-thought. They didn't want something so serious," says AB with a sigh. "After that, I didn't experiment much in my solo albums. What's the point if no one appreciates them?"

Despite his unparalleled guitar skills and his undying love for Carlos Santana and Joe Satriani, AB has only produced one instrumental album, The Sound of Silence, for similar reasons.

AB insists that he doesn't resent the fact that his audience is not yet ready to accept the kind of music he loves to play. "I don't resent it; I leave it up to time. There will come a time when there will be a huge number of listeners who love jazz, blues and funk-rock. There are already listeners of those genres, but they are few in number," he maintains.

After a lifetime of being an integral part of the music industry, Bachchu is in a unique position to commentate on the current state of our musicians and our industry. His frustrations and fears become apparent as he speaks of his ongoing battle against piracy: "The music industry should have gone a long way, but piracy has really been a setback for us. No matter how good the album is, you can only sell a limited number. By then, it is copied and distributed to everyone. A lot of people have stopped recording new songs or releasing albums; some are on the verge of closing down their studios."

"A lot of people's livelihood depends on this industry and their futures must be protected through laws and policies. The government should pay close attention to the matter immediately. We should ban the free downloading sites, for instance. Otherwise, the music industry is doomed to extinction," he argues.

Musicians have tried time and again to fight for better copyright laws, but nothing concrete has come out so far. As a sign of protest, LRB didn't release a new album for almost four years before finally releasing Juddho.

AB also believes that it is high time that we give artists royalty for using their music. "We don't get royalty if our songs are played on the radio—that's not fair, considering the radio channels depend on our music to sustain themselves. Even if they give each artist only one taka per song, they have to start the practice. All radio stations can have a uniform system." Without proper laws, regulations, and royalty, it would be impossible for musicians to make a living off of music, even in today's day and age.

According to AB, in addition to fighting for copyright, artists should also focus on creating original and inspiring music. "We are all trying to produce the same kind of music these days. You can be inspired by someone, but that doesn't mean you have to copy him/her. Of course, there are some bands and artists that have an original sound, but I think everyone should have a distinctive style," he says, adding that we need to push the boundaries and make new and better songs.

AB is thankful for his distinguished career, but he is also slightly disillusioned with the music industry. "I am still trying to figure out what the ultimate goal is in choosing professional music. I've received only one thing in my life: people's love. The amount of money I've made is spent on ensuring two meals a day. We can't dream of millions of taka, or even lakhs and lakhs of taka. Professional musicians in Bangladesh can only ask: where am I going to be tomorrow?"

Twenty years down the road, he wants to see himself as a teacher in his own music institution. He wants to play blues and jazz in his old days, when he can no longer head bang and jump around on stage. "It would also better suit my temperament then, I think," he says.

"In my lifetime, I also want to see one more thing: I want the members of the music industry to show more compassion and understanding towards each other. I would like everyone to leave their positions and all align together in solidarity in one long line. Without the support of others, individually, we won't be able to change anything in this industry," he says.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments