In whose name then?

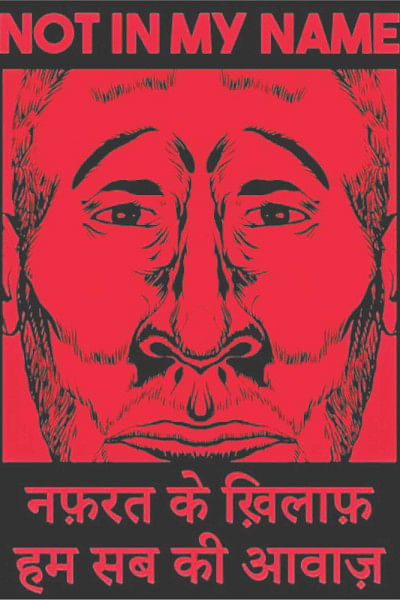

Thousands of urban Indians are taking to the streets, and many more on social media to protest against lynchings in the name of protecting cows—the sacred animal of the Hindu religion.

The lynchings have surprised many in the international community since it seems to be a moral clampdown by vigilantes on a dietary choices and religion in a developing economy which is otherwise projected as a progressive democracy.

Mob violence is not new to the subcontinent. It is not uncommon to see crowds of people resorting to assault and even lynchings against both the criminal and who they perceive to be immoral. Women are still hounded as witches in parts of the country; vehicle drivers involved in road accidents and thieves are beaten up routinely before being handed over to the authorities; corrupt officials are rowdily taken to task—mobs mete out justice frequently and dangerously.

'Hindutva' groups, which want to enforce their interpretation of the religion, have always existed in India. The violence and lynchings have been attributed to members of these groups. The number of these assaults on Muslims in the name of cow protection has gone up significantly since Narendra Modi assumed power in 2014 with a sizeable majority. While Modi himself rose to power on a plank of anti-corruption and economic reforms, a rabid section (however small in number) of the Hindu majority population has seen this as a platform for instigating and aggravating communal conflict.

Mohammad Akhlaq was killed by vigilantes in Dadri in September 2015 on mere suspicion of having beef in his refrigerator.

Zahid Rasool Bhat was killed by a petrol bomb attack on his truck in Kashmir in October 2015. It was seen as an effect of communal unrest following a 'beef party' thrown by a Kashmiri legislator.

Cow vigilantes killed Mohammad Majloom and Azad Khan in Jharkhand state in March 2016 and Abu Hanifa and Riazuddin Ali in Assam in separate incidents.

Pehlu Khan, a dairy farmer, was killed in Mewat near New Delhi in April 2017. The cow vigilantes suspected that the milch cattle he was transporting were intended for slaughter.

It was shortly after that that the Modi government framed new regulations on cow slaughter. It banned transport of cattle meant for 'non-farming' purposes. This included bullock and buffaloes as well, even though these animals do not enjoy the same sacred value in the Hindu religion as the cow.

The incident that drew the most outrage recently was that of Junaid Khan. The teenager and his brother and cousins were attacked by a mob while traveling in a train very close to New Delhi. A video of Junaid Khan's corpse shows multiple stab wounds and several contusions and other injuries on his body. Surprisingly, none of the other commuters have come forward to testify against the mob though some arrests have been made. Also, in June, deputy superintendent of police Mohammad Ayub Pandit was stripped naked and stoned to death by a mob outside the Jamia Masjid in Srinagar allegedly for taking photographs. Modi has made two statements on cow vigilantes, invoking Mahatma Gandhi in both. In the first (made in August 2016), Modi cautioned against “fake cow vigilantes”. A video of and by cow vigilantes beating up Dalits in Una, Gujarat had gone viral, triggering nationwide outrage and protests in Gujarat. While Modi pointed out that Mahatma Gandhi had been in favour of protecting the Hindus' sacred cow, there was no direct mention of the violence unleashed by cow vigilantes.

Modi's second statement was made more recently after nationwide 'Not In My Name' protests following Junaid Khan's killing. In this, he said that Mahatma Gandhi would not approve of the violence. This statement was made from Gandhi's ashram in Sabarmati and also posted on social media by the official handle of the office of the prime minister of India.

Many observers have pointed out that Modi seemed to be saying 'Not In My Name' as well, or at least 'Not In Gandhi's Name'.

Gandhi's views have been debated hotly, with many (including historians) also pointing out that the father of the Indian nation had advocated for seva (service) and not raksha (protection). An interpretation by some claims that protection is a form of service.

When the violence increased soon after Modi assumed office, it was attributed to 'fringe Hindutva groups', which was seen as an effort by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to distance itself from the violence.

However, following a recent lynching in Jharkhand, a local BJP functionary was also accused and arrested for the crime. Asgar Ansari was stopped by a mob near a village in Jharkhand's Ramgarh district supposedly on suspicion of carrying beef to Eid celebrations. The mob assaulted and killed him, less than a week after another Muslim man was attacked and his house set ablaze by cow vigilantes.

The vigilantism has grown quietly over a period of time. It was mostly restricted to rural India except for sparse incidents where some Hindu fundamentalists stormed inside restaurants and premium hotels to check their menu. That kind of vigilantism was only taken as a clampdown on a person's dietary choices. A minor section of Hindus also eat beef and it was seen as a curb on their choices too.

While vigilantism is illegal, the state of Maharashtra had tried to legitimise it. The BJP-led state administration had advertised for volunteers who would monitor the cattle slaughter ban.

“A monstrous new moral order is unfolding, irrigated by the blood of our citizens,” policy expert Pratap Bhanu Mehta wrote in a column in The Indian Express. “But this monstrosity is also wickedly clever. It is unfolding slowly, picking on individual victims, manifesting through a thousand cuts, rather than through a big cataclysm.”

There have also been concerns if this is the first of many steps by the Hindutva groups to establish a Hindu Rasthra (nation). That would only be an extension of the post-partition politics that is a burden on the country's political inheritance.

Those in the country's right-wing quarters have had a tough time defending the ideals behind cow vigilantism. Many tried to find solace within the Constitution of India which places “cow preservation” as an ideal under the Directive Principles of State Policy.

States frame their own laws on cattle slaughter and a few states did not ban it, but the new central rules have an overriding effect on the federalist nature.

The cow vigilantism has also affected the economics behind cow slaughter. Several news reports have showed how it is not just the meat but other parts of the cow that is used in several trades—not the least of them being the cow hide used in leather.

India's meat export industry is valued at US$ 4.5 billion and the dairy industry is valued at US$ 10 billion. With the vigilante crackdown on cattle transportation, there has been rising concern over the safety of dairy farmers transporting milch cattle, which cost much more than cattle that is headed for the slaughterhouses.

The new law makes the distinction between farm and non-farm purposes but the cow vigilantes have been unable to distinguish the two. In Odisha, a group of cow vigilantes assaulted the employees of a dairy who were escorting around 20 cows on a train to a government dairy in Meghalaya state.

Those supporting Modi for his economic vision have equally condemned the violence and lynchings. Some even warned that the vigilantism in name of protecting the cow had the potential to cost the BJP the next elections coming up in 2019.

With the country struggling under agrarian and other economic concerns, violence in the name of the cow or religion should probably be the last thing on any Indian's mind.

Ushinor Majumdar is a special correspondent of Outlook India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments