It's not about IT, is it?

The US Secretary of State in the 70s, Dr Henry Kissinger, after the birth of our nation, infamously dubbed Bangladesh as a 'bottomless basket' because it was considered to be a country with no hope. Some forty years later, it is still a poor nation with low literacy and an international image featuring all forms of disasters, natural and man-made.

But then again, Bangladesh - the country of 'impossible attainments'–has become the world's fifth fastest growing economy with a consistent GDP growth rate of around 6% for the last few years in a world which has seen near-zero or negative growth. Not known to many people, it has also become the world's 45th largest economy with a GDP size of USD 286 billion.With the capital Dhaka ranking third in freelance IT and IT-enabled services outsourcing globally, with over 120 million mobile phone users, 43 million internet users, 8 million Facebook users (one new Facebook user being added every twenty seconds), 99% geographical coverage in voice and data connectivity (mostly through wireless networks), and over 5,000 service access points where the citizens receive over sixty government and private services electronically, the country is on the fast lane towards massive digitisation. The government service delivery mechanism is reinventing itself to become more citizen-centric and responsive to citizens' needs. In spite of overwhelming odds, the government officials are showing a distinct change in 'mind-set' to become more digitally oriented and service focused.

Taking services to citizens doorsteps

In the nondescript backwaters of Bangladesh, traditional slow, archaic rules-driven service delivery is changing and so is the approach of government service providers. In a matter of six years, hundreds of e-services have sprung up throughout the country. Citizens can now pay their electricity, gas and phone bills online; download English lessons and consult with a doctor remotely through mobile phones. Over 4,500 rural local government institutions have established Union Digital Centres (UDC) where every month, over four million hard-to-reach citizens electronically access diverse critical services such as birth registration, land records, exam results, registration for work permits abroad, telemedicine, and timely information on agriculture. Financial inclusion has been expanded through mobile banking, payment of utility bills, and first ever introduction of life insurance in rural areas. In the last 4 years, 115 million electronic services have been provided from the UDCs.

A typical citizen now walks only 3 km to the nearby UDC to access critical services, saving time, money and harassment of going to the district headquarters 30-50 kilometres away. Delivery time has come down from 20-30 days to as little as one hour. Each digital centre is managed by a pair of local entrepreneurs – one man and one woman. The gender empowerment aspect of this transformation in public service delivery is undeniable given that most women can go to the UDCs to access services whereas it was much more difficult, if not entirely impossible, for them to travel to sub-district or district offices earlier. Sufia Begum of Satkhira district, who registered for unskilled labour employment overseas, was selected for a housekeeping job in Hong Kong. She said, “I was pressurised by a manpower trader to give him nearly BDT 200,000 (USD 2,600) just to get started, but I had heard horror stories of how people lost everything to these unscrupulous traders. Instead, I registered electronically for BDT 50 (USD 0.60) through the UDC near my house and paid BDT 40,000 (USD 510) when I got selected for the job in Hong Kong.” These ICT-enabled one-stop shops represent significant decentralisation of the government service delivery mechanism, introduction of private services through innovative public-private-partnership arrangement, self-employment and women's empowerment. Through a grass-roots social networking platform, UDCs have also played a major role in giving rural citizens a voice and creating further demand for improved service delivery.

Preventing Digital Divide and reducing TCV

Digital Divide is the gap between the ICT-haves and the ICT-have-nots. Typically the introduction of ICTs in most economies happens in a top-down manner first benefiting the advantaged class and further exacerbating the socio-economic divide. Most major international donors express concern about Digital Divide. However, in Bangladesh, the deliberate decision was to introduce ICTs in union parishads before going to pourashavas and city corporations. This prevented not only the Digital Divide but is also now slowly reducing the economic, social and education divide.

An illustration of the power of ICTs in grassroots is the dramatic example of birth registration. In the 131 years between 1873 and 2004, only 8 percent of the population were registered. In contrast, the picture painted in the 10 years between 2004 and 2014: nearly 130 million citizens out of 160 million, an 80% coverage, was achieved. This tremendous result can be squarely attributed to the availability of an electronic birth registration system that was decentralised to the more than 4,500 union parishads first and then to pourashavas and wards of city corporations.

In another example, all sixty-four DC offices have taken a pioneering initiative with the Ministry of Land to digitise about forty five million land records. To most rural citizens of Bangladesh, the DC Office is as 'high' as the government gets, and delivers a number of vital services, land records being one of them. In the last two years, the DC offices have delivered over three million land records electronically – with a large number of applications coming through the Union Digital Centres. This has saved citizens enormous travel time and huge expenses which traditionally included not only travel costs but also 'speed' money.

Moreover, the government has created one single address, www.bangladesh.gov.bd, for all its information and services by virtually uniting all twenty five thousand of its offices under one web portal. Possibly one of the largest government information portals under one umbrella in the world, this is the most visible implementation of proactive information disclosure under the Right to Information Act in Bangladesh. Another portal, www.services.portal.gov.bd, has accumulated detailed information on four hundred and fifty services from forty ministries and agencies in one location. A third portal, www.forms.gov.bd, has collected over a thousand government forms in one location.

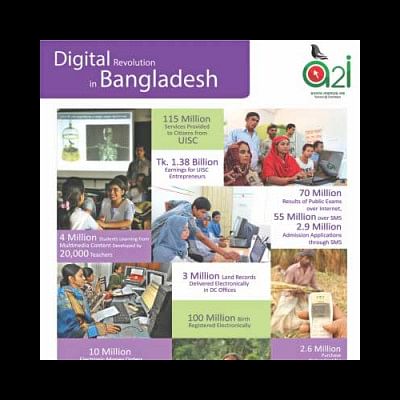

The battle cry of the innovative transformation using ICTs was kept simple and easy to understand for the public service providers: “Service at Doorsteps” characterised by TCV, an acronym to capture 3 simple parameters from the perspective of the citizens: time (T) to receive a service from application to final delivery, cost (C) to receive a service including all cost components including real and opportunity costs from application to final delivery, andthe number of visits (V) to various government offices from application to final delivery. The infographic 'Digital Revolution in Bangladesh' illustrates some staggering numbers relating to the electronic service delivery from the government to citizens.The reduction in TCV for services is equally mind blowing: 88% reduction in time, 25% in cost and 35% in visits for obtaining citizens' certificates, 92% reduction in time and 76% in cost to pay electricity bills, 82% reduction in time and 65% in cost to access banking services.

ICT for automation or for service delivery?

The famous British playwright George Bernard Shawsaid, “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” Bangladesh played the role of the reasonable man for a long time looking at ICT through the lens of automation. It is only recently that the country's government has started changing its perspective to that of the unreasonable man and created an intense focus on service delivery with a secondary focus on automation only when needed to support service delivery.

The term e-Governance is not new in Bangladesh. Since the 1980s, the country has been automating the functions of our government offices. Many government organisations boast success stories of automating internal processes such as human resource management and payroll processing, inventory management system, library management system, among several others. Millions of dollars of hardware was procured to set up server rooms - some state-of-the-art rivalling those in developed countries. Software, though much less in terms of procurement figures compared to hardware, has added to the ICT arsenal used for automating our government business processes.

Citizens naturally have the right to ask how much direct, or even indirect, benefits such internal automation has brought for them to improve the quality of services the government renders to the citizens. Whether the payroll processing of a government department becomes more efficient, whether government offices become more communicative or transparent because they are using more ICTs more frequently, or whether file administration becomes quicker - it has no bearing to a citizen's lives unless the services they receive from the government come at a lower cost, take less time and they have to make fewer trips and run around to fewer desks. The use of ICTs within the government, if it does not improve service delivery, no matter how much faster it makes the internal processes, will ultimately amount to an illusion of good governance without real change. Citizens will at some point wake up to the reality that in the name of 'modernisation', the government is wasting citizens' hard-earned tax money.

The Digital Bangladesh vision of transforming government services to e-Services is citizen-centric and pro-poor. It is eventually about improving the lives of the common citizens. If ICTs can make that improvement, those ICTs are to be considered. The use of ICTs that do not make that improvement noticeably, even if indirectly, do not belong to this vision.

The case of twenty thousand sugarcane farmers in Faridpur and Jhenidah is a telling example of whether one needs to start with automation to end up in service delivery. Since 1932, the purchase order, called 'purjee', was sent out to sugarcane growers on paper. Often taking an unpredictable amount of time to reach farmers, the purjee would sometimes get lost, and even sometimes fall prey to the unscrupulous practices of better 'connected' farmers keen to ensure their own harvests a timelier – and valuable - crushing schedule. The farmers receiving late notification would not be able to bring their harvest at the right time, losing vital income because of a loss of weight of sugarcanes, and in extreme cases, a total failure to sell the harvest. Furthermore, delays in purjee issuing, and the unpredictable delivery of sugarcanes they cause, would sometimes result in local mills running at below capacity, causing significant loss of public resources. The e-Purjee Information Service, introduced in late 2009,replaces the paper notification with an instant SMS notification which informs the grower that his purjee has been issued and that he may start preparing his harvest for supply to the mills. Nowadays, two lakh sugarcane farmers receive purchase orders through SMS.

The citizen-centric, pro-poor nature of this approach is demonstrated in how the service was visualised. It was visualised with the citizens in mind. The end customers are sugarcane farmers, and not the sugar mill management. If the initiative was started with the management perspective, the work would have surely begun with internal automation – payroll processing, accounts automation, inventory management, inputs and outputs tracking and many other such things. The initiative would ultimately address the purjee systems perhaps after doing expensive and time-consuming internal automation; or perhaps not if the funds ran out, management changed focus, ICTs took a lower priority for various reasons (as is often the case), or the end customers were deemed unimportant (which is even more often the case). Since, in this case, the work started with the end customers' perspective, the largest citizens' benefits were achieved with very little investment in hardware, software and human resources support. In contrast, internal automation projects typically require much larger investment in all these three.

The partners in crime of Digital Bangladesh

Digital Bangladesh is the vision of a country with middle-income status where ICTs are used as a pro-poor tool to eradicate poverty, establish good governance, ensure social equity through quality education, healthcare and law enforcement for all, and prepare the people for climate change. Digital Bangladesh is not a promise for a different world. It is actually a promise for the same world, much better, much quicker, much more responsive and less costly. At the same time, it is a different world to different people. To a student, it is higher quality of education and being market-ready; to a farmer, it is right information at the right time at the right place; to a patient, it is access to quality healthcare without having to stand in long queues for days; to a serving government officer, it is triumph of merit and performance over connections; to a retired government officer, to a freedom fighter, and to a widow, it is delivery of safety nets and pensions transparently. To all, it is services they deserve and expect at their doorsteps.

As such, Digital Bangladesh is everybody's business. Our sixth five-year plan, the upcoming seventh five-year plan, Strategic Priorities of Digital Bangladesh Report and ICT Policy outline the responsibilities of almost all ministries and many agencies who will make the reality of Digital Bangladesh come alive. A few ministries have taken the role of co-ordination and linking to the different organs of planning and implementation. The Prime Minister's Office through its Access to Information Programme (a2i), with technical support from UNDP and USAID, has been spearheading this transformation. The Cabinet Division has led the implementation through the divisional commissioners, DCs and UNOs who co-ordinate service delivery from the district and upazila offices of the line ministries to most citizens of the country. It has formed the Co-ordination and Reform Unit with a Secretary at its helm: reforms facilitated by ICT is a major agenda of that unit. The Ministry of Public Administration has been active with several policy reforms that have slowly but fundamentally started changing the rules of governance. For instance, the age-old Secretariat Instructions have been updated to include electronic filing, digital signatures, digital archiving of files, proactive information disclosure according to the Right to Information Act, electronic grievance redress system, among many other policy changes, some of which may be considered 'radical' by Dr Kissinger. The Local Government Division led the remarkable establishment and nurturing of the Union Digital Centres across the country. The Ministry of Posts, Telecommunications and ICT has been instrumental in setting up high-speed internet connectivity infrastructure in the tens of thousands of government offices, schools, and hospitals, and cutting-edge data centres to host the digital nerve centre of the entire government. The Ministry of Education has demonstrated that teaching-learning of general subjects in the classroom can be improved by using digital materials from the internet and by catalysing massive collaboration amongst teachers through a teachers' portal. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has distributed thousands of laptops and tablets amongst the grassroots level health workers who are sending health data directly into the servers thereby generating real-time statistics without having to wait for time-consuming and expensive manual data entry, error correction and sophisticated statistical processing.

Collaborating and competing to do good

The country-wide initiative of the UDCs and DC Offices is exerting pressure and is creating a sense of competition amongst the other offices of the government including the Ministries and Directorates who are changing their focus from automation to service delivery using ICTs.Each DC office now features a dashboard that show citizens' electronic requests and internal e-files being generated and disposed of. PMO and Cabinet Division monitor these dashboards to determine the effectiveness of the DCs in dispensing services and making decisions. The Cabinet Division reformed the concept of the government CIO from Chief Information Officer to Chief Innovation Officer, and mandated formation of Innovation Teams in all ministries, departments, districts and sub-districts. These Innovation Teams are actively working together to reduce TCV (Time, Cost and Visits) associated with hundreds of services. They are making very active use of social media to collaborate with and learn from each other. There are closed social media circles for many government departments now. Since late 2014, each DC has featured an open Facebook page to communicate with its constituency and to address grievances.

Bureaucracy worldwide is more or less risk-averse by nature and by design. In a conservative country like Bangladesh, it is perhaps more so. Since innovation comes with possible risks, innovation in the system is discouraged and even penalised. Yet, innovators exist in the bureaucracy and appreciate an opportunity to exercise their mettle. The Access to Information (a2i) Programme of the PMO recently launched a Service Innovation Fund which provides financial support to prototype an innovation. a2i also provides the policy support from the highest office of the government that creates a risk-free (or less risky) space to implement the innovation. It was decided to open up the fund to non-government innovators since brilliant ideas to improve public services started coming in from companies, NGOs, academicians and students. In the last year and a half since this fund was launched, over a thousand proposals have come in. Thirty five small awards were given out to a range of organisations: an upazila agricultural extension officer to develop a new low-cost but effective crop disease diagnostic system using digital images, an NGO to convert all 100 of our primary and secondary textbooks into digital talking books for the visually disabled, a small company to develop a 3D printing system to print low-cost prosthetic limbs, a government directorate to develop an internet and mobile-based learning system for millions of expatriate workers, and the list goes on.

So far, we have seen just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what kind of leapfrogging we can do by working together and competing for excellence. The avalanche effect that is yet to come is just a matter of time. What would Dr Kissinger say today?

................................................................

The writer is Policy Advisor, Access to Information Programme, Prime Minister's Office

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments