Padma Bridge: Bonding old terrain and forging regional integration

The great poet Rabindranath Tagore used to frequent his tenants in Kushtia, Rajshahi and Pabna during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in a boat plying in and across the Padma, Gorai, Chalan Beel and other smaller rivers and water bodies. A memorabilia of the boat has been kept at Kuthibari, Shilaidaha, for posterity to look at in musing reverence. Had the sage been living now, other things remaining the same, he would need no boat, but take a train ride or a car from his ancestral home at Jorasanko and see a railway bridge (the Hardinge Bridge) and a parallel road bridge over the Padma (the Lalon Shah Setu or the first Padma Bridge) and roads of most sizes and shapes built connecting the villages he went to.

Reunite

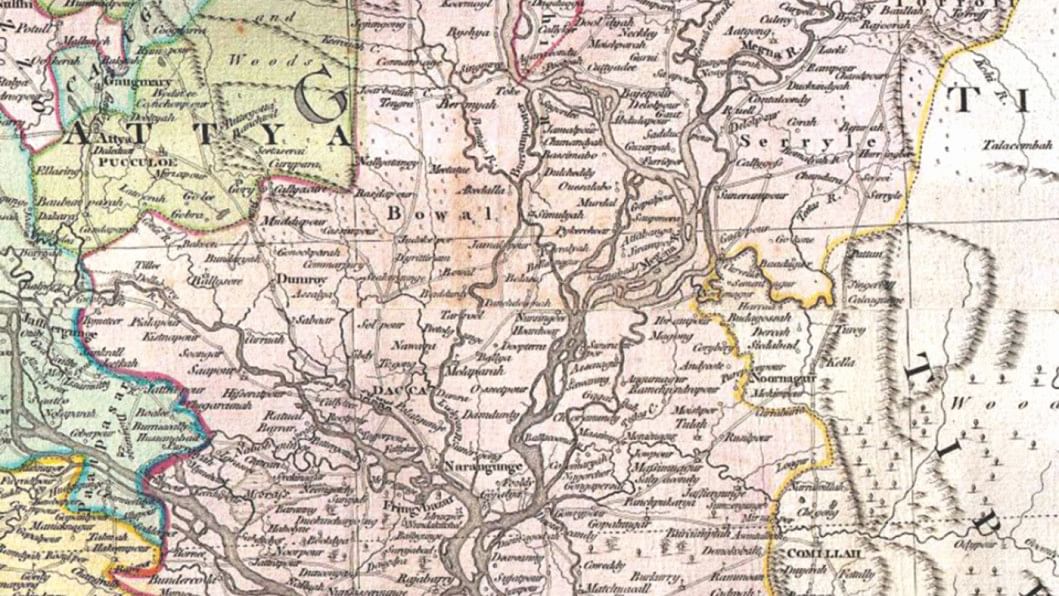

About a hundred years before Tagore's birth, the British East India Company, in the first decade of its ascendency in Bengal, had employed Major James Rennell to survey the newly acquired territory. Rennel completed his work with extraordinary dexterity and aplomb and published in 1776 his 'wall map'. The Padma at that time flowed southward between Panchar and 'Rajanagur' straight towards 'Dakin Shahbajpour' in the Bay of Bengal; and the place—where the Bengalis, nearly two and a half centuries later, are now building the second Padma Bridge was, for all practical purposes—a contiguous landmass criss-crossed by only rivulets and canals. One of the them was 'Callygonga'. Had Rennell been here today, he would draw a different map for much of East Bengal, with the Padma leaving the southward course and moving eastward to join Meghna near Chandpur. All the land between Rajanagur and the west bank of Meghna to the east had been devoured in Padma's new course. He would see that the great mythological river Brahmaputra had become thin beyond recognition for most trails, leaving only a trickle of water near the holy site of Langalbandha. He would also find Brahmaputra's huge volume of water had, in order to look for the 'shortest route to sea', created the new river Jamuna. Such are the vagaries of riveting rivers of Bengal. Be that as it may, this second Padma Bridge is going to reunite Rennell's unbroken stretch of terrain.

If this second Padma Bridge is completed, it will be the largest ever edifice, opening doors and making dreams possible for future bridges at Bahaduarabad-Fulchorighat and Chandpur-Shariatpur, and may be, even at Daulatdia-Paturia and Aricha-Nagarbari venture. The first one would be remembered for the swiftness of its completion and the great role it would be making in the years to come in regional co-operation and integration. In a spatially small country like ours, transport facilities must have an inter-country pro-neighbour dimension to give it some needed depth and extra importance.

One of the purported tasks of the second Padma Bridge linking Mongla Port with the economic heart of the country around Dhaka might take a secondary role over time, considering that the Poshur River is never a serious contender to host big ships—what had happened to the Chalna Port is a case in point. However, 20 of the country's 64 districts—those of Khulna and Barisal divisions and of Greater Faridpur—with about 19% of the total population, would need the bridge for the swiftest road link to the capital; and that in itself is a huge agenda. A future new link-up with Kolkata through road and rail is another mouth-watering prospect and adds to the utility of the bridge. Besides, attractive tourist destinations like Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's mazar in Tungipara and the UNESCO World Heritage site of the Sundarbans are to grow in acclaim and demand over time, adding to the economic justification for the construction of the bridge.

And now Payra of Patuakhali has come into the picture: if the deep-sea port is completed with all modern facilities and in time, this bridge will have a thousand and one reasons to stand up and need no other economic validation. Policy-makers have taken decisions to make Payra the largest port in the country. The very idea of Payra deep-sea port calls for taking up projects for multi-lane expressways and railway lines connecting with the capital city right now. Payra can also be a port for for Bhutan and Eastern Nepal and the North-Eastern states of India, and who knows, maybe one day for Tibet of China too.

Jolt on the way

Unlike the first bridge, this second one has had a longer history with a jolt on the way. First conceived in 1999, its pre-feasibility report was prepared in the year 2000. JICA, the Japanese donor agency, got the Feasibility Study completed in 2003-2005. The bridge's project concept paper went before the ECNEC in 2005. Besides the following other important studies were completed by 2006:

- Land Acquisition Plan, June 2006,

- Resettlement Action Plan, June 2006,

- Environmental Management Plan, June 2006, and

- Preparing the Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project, September 2006

The military-sponsored government of 2007-2008 approved the Padma Bridge Project for implementation, but real work had not started in 2008. From 2009 onwards, the bridge project gained further speed. A new study titled 'Detailed design of the Padma Multipurpose Bridge, Bangladesh – An overview' was completed in 2010. However, the withdrawal of donors in 2012 came as a jolt for the project, putting its execution behind schedule.

Domestic funding has now been mobilised, and the construction of the bridge proper started last December 2015. It is evident the Bangladesh policy-makers and officials took the completion of the bridge as a challenge; and although both time and cost have increased, the bridge-construction process is now a regular item on newspapers and television channels and in the minds of the people.

There is hardly any ground to fear that drawing only domestic funding would leave less money for such important sectors like education, health and social welfare. Recent budget figures have disproved this; and although economists will continue to debate the opportunity costs involved, the bridge's addition of over 1.2% to the GDP should put to rest all argument.

It is important to note that international standards as acceptable to previous donors have been retained. For one thing, the 'Social Action Plan', or SAP, done to fulfil requirements of would be co-financiers is in place. SAP includes, among other things, Social Assessment, Resettlement Site Development, Resettlement Framework, Public Consultation and participation, Charland Monitoring and Management Framework, Gender Action Plan and Public Health Action Plan. Besides, environment has been given serious and thorough attention to, as evident from the Environment Management Plan.

Apart from road and railway transport, poverty reduction was another aspect that got great attention to as an immediate after-effect of the Padma Bridge. An Asian Development Bank document prepared for its Board read: ''The southwest zone has one of the highest poverty rates in Bangladesh, according to the household income and expenditure survey conducted in 2005. While 42% of the population of the whole country lived below the absolute poverty line, the southwest zone had a poverty incidence of 52% in Barisal Division and 46% in Khulna Division. During construction, local unemployed people will gain employment, and increased commercial activity will generate income. The country will be physically integrated through the fixed link, reducing economic disparity and deprivation. An estimate of multiplier effects on the project investment shows the bridge increasing the gross domestic product growth rate by 1.2% and the regional growth rate in the southwest zone by 3.5%, generating 743,000 person-years of additional employment, and thereby contributing 1.2% of the total labour market of Bangladesh. Over the long term, the bridge's impact on poverty reduction will be more significant, as the share of economic benefits generated by the bridge that will accrue to the poor is larger than the share of the gross domestic product that goes to the poor.'' This truly is the economics of the Padma Bridge.

After completion

The completed bridge will have, among others thing: (i) a two-level steel truss composite bridge 6.15 km long – the top deck to accommodate a four-lane highway for vehicles and the lower deck to accommodate a single-track railway to be added in the future (ii) River Training Works on both banks (14 km in total), (iii) Janjira Approach Road and Selected Bridge End Facilities (10.5 km in length), (iv) Mawa Approach Road and Selected Bridge End Facilities (1.5 km in length), and (v) Service Area-2 in number. There will be provision for gas and telephone lines and also for electricity transmission. A total of 41,600 vehicles are projected to use the bridge daily in the year 2025 and the EIRR (Economic Internal Rate of Return) was calculated to 14.80% in the Feasibility Study. No doubt the figure of vehicles will go up considering Bangladesh's high rate of projected economic growth.

According to one study, economic and financial analyses took into account regional economic development, resulting changes in transport costs and accessibility, impact on poverty reduction and toll harmonisation for both Padma and Jamuna Bridge. It also took into account various aspects of loan, but since loans are not a part of costs any longer, they may be overlooked for the time being. Under this study, a benefit-cost ratio (BCR) of 4.4 and an economic internal rate of return well in excess of the economic opportunity cost was calculated.

Dimension of regional integration

The above-mentioned Asian Development Bank document noted: “The Bridge is expected to have sub-regional impacts by forming part of the Asian Highway Route A-1, the main Asian Highway route connecting Asia to Europe.' The Feasibility Study Report also mentioned of 'promotion of international trades between neighbouring countries.'

With the ADB-sponsored South Asia Sub-regional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) Program in operation since the year 2001 and over six billion dollars worth of project implemented so far, the sub-regional grouping holds key to greater regional economic integration with completion of the Bridge. Besides, Bangladesh's own projects have regional dimension too.

By all counts, the bridge will have the greatest of impacts on regional co-operation with its road and rail connection with the super-hungry areas around Dhaka and Kolkata metropolises. Onward connections to other parts of the SAARC fraternity will tend to become easier. That underlined by genuine political rapprochement could make South Asia the world's largest economic grouping—a real South Asian Union. It is noteworthy that under the SAARC and BIMSTEC platforms, there are already far-reaching connectivity ideas floating that would bring the length and breadth of region closer.

One important SASEC railway project is 'Investment in infrastructure and rolling stock, (e.g., Dhaka- Chittagong and Dhaka- Darsana-Khulna corridors)'. This later part will no doubt have new importance once the bridge is open with its lower-deck rail track. However, connections to Dhaka from Mawa and from Janzira to Bhanga (in Faridpur) and beyond have to be built at the soonest to get the best out of the proposed rail track facility on the bridge.

The railway line completion work is exigency, given the real worth of the location of the bridge. Once it is in place and operational, connecting the hearts of the two parts of historical Bengal, it will not only be a great boon for the land of Atish Dipankar and Alaol, Tagore and Nazrul, but also for the areas beyond—to the west and the south-west and to the east and the north-east. The Padma Bridge will be a major plank in all such dream.

A lot remains to be done for true coming together of the South Asian countries. An SAU (South Asian Union) on the model of EU remains a far cry. Sadly, only 5% of total foreign trade now take place internally among SAARC countries, a fact that has prompted writers to note that the SAARC region is the least integrated geographical area of the world.

On the SASEC front, the picture is a bit brighter. SASEC Road Corridor (lmphal-Silchar- Karimganj- Sutarkandi-Sylhet sections) and Rail Corridor projects (Dhaka-Chittagong and Dhaka-Darsana-Khulna; Dohazari-Cox's Bazar to Gundum; and Enhancement of Railway Connections between Bangladesh and India) add another argument for the Padma Bridge. A railway wagon or a bus or a truck from Agartala or Silchar towards India's mainland will no doubt prefer the Padma Bridge route. Bangladesh has suggested giving priority under the SASEC platform for the revival of railway connections between India and Bangladesh at the places that used to be functional in the 1940s. Whereas reviving the pre-1947 lines is very important, the new line from Dhaka to the economic hub of West Bengal through the Padma Bridge is a case of endless viability. The thickly populated areas that fall on the routes and in the hinterland crave for such a link. The Padma Bridge promises to be the greatest thing ever built in this country; and given the benefits it will accrue, it might prove equally delectable to our near and not-too-distant neighbours.

The writer is former secretary of the Government of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments