Khadi diaries

“When they sell, copper turns to gold but when we do, that very same gold becomes dust…”

As depressing as it may sound, these are the very words Chintaharan Debnath used to depict the current state of the handloom khadi industry in Bangladesh.

“Business is dead! We cannot even get 'katunis' to spin the cotton for us!” added the master crafter who once had a thriving business. Blaming the middlemen for being dishonest and deceiving the labourers of their dues, Chintaharan Debnath was quite sceptical about the future.

“Do you think we haven't seen reporters cover this story before? Things will never change, if the system doesn't!

As long as people in the trade do not respect our hard work and learn to value the difference between automation and artisanship, nothing will ever change!” said a dejected Debnath with all the weight in his heart.

To get a hold of the backdrop, we travelled as far as Chandina, Cumilla, to a village called Debidwar, where several families still deal with khadi commerce, trying to make a living out of the age-old trade.

Ranjit Debnath, another merchant of the khadi trade was slightly more positive about the circumstances.

“I would not say the trade is dead, but the originality has certainly been tampered with. Today, the entire world is inclined towards fast paced automation. Handloom has been replaced by power looms to make way for the increase in demand and deal with the rising costs. We must also take into consideration that handlooms are uber expensive, and takes a lot of time to manufacture; in a free market economy, transition towards a faster paced alternative is inevitable, but that does not necessarily mean that we can forget our past or our heritage,” articulated the knowledgeable tradesman.

What Ranjit Debnath probably meant is that end-products of handloom will always be more expensive compared to machine produced items, but they would also be inimitable; with no two products telling the same story.

Thus, this exclusivity must be appreciated by everyone, especially those involved in the chain of trade —middlemen, traders, retailers and customers.

“A master weaver can weave 15 metres of khadi fabric by hand in an entire day whereas in the case of automation, more than 150 gauges can be produced; that too using just one machine! But in the former case, the handiwork will always be different with a unique story to tell on each fabric — we need to know the difference,” reiterated Chintaharan Debnath.

Probir Shaha, another trader of 'deshi' fabrics helped us get around the village, meet with the local artisans, craftsmen and also witness a traditional 'khadi gaddi' and a loom factory upfront.

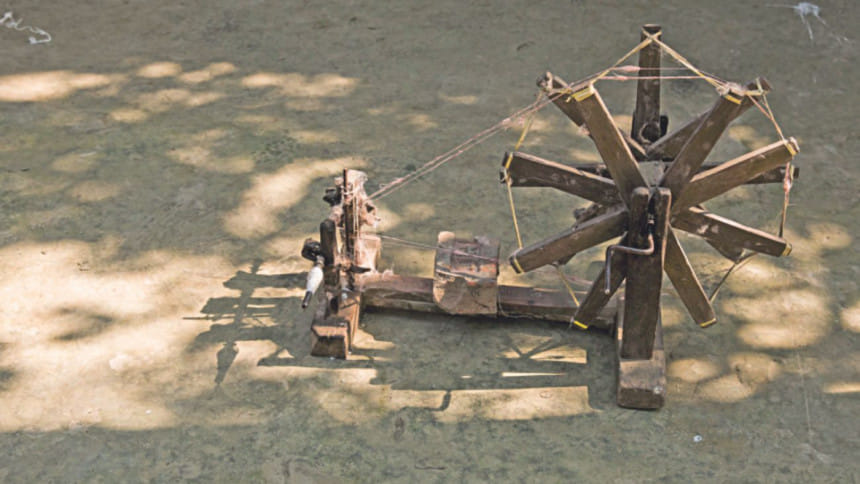

Sadly, everything looked rusty; the charkas collecting dust, sitting idle in the far corner of rooms with thatched roofs. The wooden looms replaced by enormous modern machines of steel and cast iron; cotton spinners, 'katunis' completely absent from the scene — probably employed at the local garments factory, earning a much higher salary compared to the meagre amount of Tk 10 to Tk 30 per hour assigned to cotton spinners on an average.

“How can we offer more? The middlemen don't want to pay one taka extra for our efforts! If we raise the wages, the end price would spike and that means a lot of good fabric would be wasted because no one wants to pay for them,” said Chintaharan Debnath while revealing the complex situation.

Prabir Shaha also narrated the sad story of how he had to let go of his father's handloom khadi factory, and incorporate power looms into the system to get on with earning a living. “It's not my fault, the world has moved on, and so must we – if we are to live!” he said.

What people are ready to pay for is what power looms supply, but that is not khadi! Even the threads are imported from abroad – formerly, the cotton was produced in Bangladesh, often collected from the wastage of cotton mills and then churned into thread by the ultra-poor, using a charka.

Expert artisans would later spend an entire day weaving exceptional, time consuming pieces on the 'hathkargha,' producing a coarse material that breathes on its own; providing warmth to the wearer in winter and coolness in summer.

Nowadays, what we get in the name of khadi are fine cotton clothes, produced in mills in Narayanganj, with thousands of exact copies of every single design. These clothes, although comfortable and good looking, cannot be termed as the same khadi brought to Bangladesh by the 'Swadeshi Andolon' or Mahatma Gandhi himself,” said Prabir Shaha.

HISTORY OF HANDLOOM AND KHADI

To properly cite history, we must go a long way back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, where cotton textiles and weaving looms had a strong presence. These facts have been confirmed by archaeologists, from the evidence they discovered at the excavated sites of Mohenjo-Daro.

Fast forward to the 13th century, cotton textiles were exported from greater India to China, Indonesia, Far East, and even to some parts of Europe, before the Europeans actually took over India.

Few centuries later, the first cotton mill in greater India began operating in 1854 in Bombay (present day Mumbai). But just a few years later, due to export of huge amounts of yarn to Britain causing countrywide scarcity and an additional influx of cheaper imported material from Lancashire mills, the production of khadi, a contemporary social fabric, had been viciously disrupted, along with many other handloom fabrics of the Indian subcontinent.

However, the 1920s saw a revival of khadi again, thanks to Gandhi, who had the vision to boycott foreign goods, and provide a unique opportunity to every man, woman, and child of greater India to maintain self-discipline and self-sacrifice as part of the nationalistic movement, Swadeshi Andolon.

Acharya Vinoba Bhave, chosen as the first 'Satyagrahi' by Gandhi himself, had once articulated that if Gandhi did not come up with the idea of non-violence and non-cooperation, someone else would have on a later date, because it was a historical necessity, but if 'Bapu' had not promoted or thought of khadi as an instrument to fight back, if he did not endorse Khadi so intensely, no one in the world would have imagined it…it got a second life only because 'Bapu' wanted Khadi as a permanent solution to poverty alleviation, employment, national reliance, dignity and so much more.

KHADI CULTURE IN BANGLADESH

Although many will tell us that it is through the Swadeshi Andolon and Mahatma Gandhi that khadi entered Bengal, historians have cited that even in the 6th century, a local variation of a coarse cotton fabric resembling khadi had been described by travellers.

The Tripura Gazetteer depicts that the khadi weaves from Cumilla, Mainamati, Gouripur, and Muradnagar had been renowned even during the Mughal period, as valuable textiles with distinctive characteristics.

Khadi, however, did gain momentum in Bengal after the Swadeshi Andolon, and the winds of change in greater India. Mahatma Gandhi encouraged the local weavers to support khadi, and consequently, in 1921, a branch of Nikhil Bharat Tantubai Samity had been established in Chandina, Cumilla. This was arranged in order to export khadi from Bengal to major cities in India to meet with the increase in demands.

Later, in 1952, Dr Akhter Hamid Khan and Governor Firoz Khan Noon established The Khadi Cottage Industry Association, and a khadi specialist was brought in from India along with 400 charkhas to train, improve and assist in production.

However, all the initiatives were dampened after the Indian independence and the following Pakistani rule. Sadly, today, even after 40 years of the sovereignty of Bangladesh, designers and retailers have failed to restore and resurrect the production of khadi, transforming it into an almost forgotten craft.

THE FUTURE

Khadi's past depicts that this very trade has faced numerous upheavals over many centuries, coming out stronger every single time. Competition from power looms is not new, ever more so in the future, especially with the emergence of Artificial Intelligence.

But yet again, Chintaharan Debnath's words remain — “No matter what, exquisite heritage products must not be manipulated with or forgotten completely, because heritage is the backbone of a nation, it defines its very existence”.

There would always be a niche market for the authentic khadi, even in the age of power mills and nylon. Thereby, those of us who care for authentic products must be ready to pay the proper price to value the entire chain of production. Otherwise, unique crafts like the khadi weave will soon be forgotten; lost to the pages of history, and only passed down as stories.

With this valuable trip to Chandina, we learnt that with our combined awareness, the soon- to-be-dead industry of the authentic khadi could be sustained — at least for connoisseurs of everything vintage.

By Mehrin Mubdi Chowdhury

Photo: Sazzad Ibne Sayed

Location: Debidwar, Chandina, Cumilla

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments