Technological revolution and the jobs of tomorrow

Today's technological revolution has given rise to a digital economy, which includes the Internet (fixed and mobile broadband), cloud computing, smartphones, smart cities, the Internet of Things and Internet of Everything, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning, Big Data analytics, Blockchain and others. History has already witnessed industrial revolutions associated with technology—the first one was driven by steam, the second by electricity, the third by digital revolution, and the fourth by artificial intelligence.

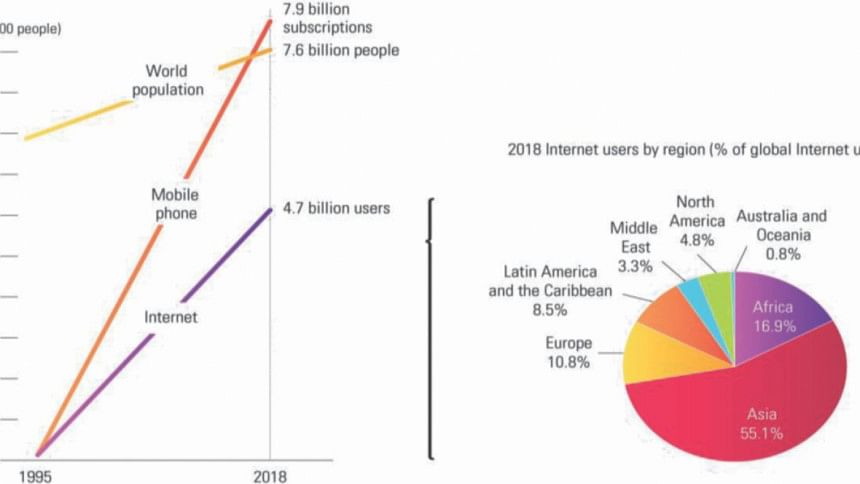

The ICT infrastructure expansion, and Internet and mobile phone access empower people to harness their creativity and ingenuity and allow much more information to be shared than any other means of communication had. The amount of digital data has doubled every three years since 2000, and today less than 2 percent of stored information is offline. In 2018 there were 4.7 billion Internet users, 7.9 billion mobile subscriptions and over 5 billion people had mobile subscriptions (see figure). By 2025 the number of unique mobile subscribers will reach 5.9 billion, equivalent to 71 percent of the world's population.

The impact of technology on the economy is undeniable. Global high-technology exports have more than doubled in the last 15 years, from USD 987 billion in 1999 to USD 2,147 billion in 2014. In 2016, global exports of ICT services increased by 5 percent, from USD 470 billion to USD 493 billion. Artificial Intelligence, robotics and other forms of smart automation could add an estimated USD 15.7 trillion to the global economy by 2030.

People with the skills and resources to use technology and create value can thrive in today's digital world. But the digital economy presents skill-biased technical change: the idea that the net effect of new technologies reduces demand for less skilled workers while increasing demand for highly skilled ones. By definition, such change favours people with higher human capital, polarising work opportunities.

Globally, 133 million new high-skill jobs are estimated to emerge by 2022, but 75 million jobs may be displaced by automation and new technologies. Among the new roles that are expected to experience increasing demand are Data Scientists and Analysts, E-commerce and Social Media Specialists, Training and Development, Innovation Managers, AI and Machine Learning Specialists, Big Data Specialists, Information Security Analysts, and Process Automation Experts. By mid-2030s an estimated 30 percent of jobs and 44 percent workers with low-skills and education will be at potential risk of automation

THE CHANGING NATURE OF WORK

In the digital economy the nature of work has changed with the introduction of new ways working including flexible work, new ways of communicating, new products and new demands for skills. New technologies are also reinforcing and deepening previous trends in economic globalisation, bringing workers and businesses into a global network through outsourcing and global value chains. These processes are reshaping work and testing national and international policies.

In many areas of work, the labour market is now global. Multinational corporations have access to labour around the world, and workers must compete on a global scale for jobs. Digital technologies heighten the competition by removing geographical barriers between workers and work demands—in many cases it is not even necessary for a company to move physically or for a worker to migrate. The work connection can be made through the Internet or mobile phones. That there is a global labour surplus makes competition among workers even fiercer.

Consumer demands have also evolved with expectations for low-priced consumer goods, for fresh and new products and for digital access to products from around the world. This has increased competition for companies to provide cheap, innovative products that cater to rapidly changing trends, all the more so as digital technologies allow companies immediate and constant access to information on consumer habits and interests. A flexible approach to production and cost cutting, including labour costs, has been the producer response. Low labour costs and flexible commitments to workers allow companies to quickly and efficiently respond to shifts in consumer needs and in the location of demand.

For workers these trends are aligning to create a world of work where creativity, skills, ingenuity and flexibility are critical. But even for those who are well positioned to compete in the emerging work system, security is lacking. Only one in four people worldwide works with a full-time, permanent contract; for those in wage and salaried employment, three out of five workers are in part-time or temporary work. With just 30 percent of the world's labour force covered by unemployment protection, a world of work that values flexibility may be a challenge to the stability of worker's lives.

The digital economy may be associated with high-tech industries, but it is also influencing a whole range of more informal activities from agriculture to street vending. Some may be directly related to mobile devices. In Ethiopia farmers use mobile phones to check coffee prices. In some villages in Bangladesh female entrepreneurs use their phones to provide paid services for neighbours. In India farmers and fishers who track weather conditions and compare wholesale prices through mobile phones increased their profits by 8 percent, and better access to information resulted in a 4 percent drop in prices for consumers. In countries as diverse as Malaysia, Mexico and Morocco, small and medium-sized enterprises with Internet access averaged 11 percent productivity gain by reducing transaction costs and barriers to market entry.

The Internet and mobile technologies create new jobs directly through demand for labour from new technology-based enterprises and indirectly through demand from the wider ecosystem of companies created to support technology-based enterprises, such as network installation, maintenance providers and providers of skill-based services such as advertising and accounting. Mobile phones are extending the reach of agricultural extension services. One application developed in Kenya is iCow, which helps cattle farmers maximise breeding potential by tracking their animals' fertility cycles. Mobile services can match employees with vacancies. In South Africa the extension of mobile phone coverage is associated with a 15 percent increase in employment, mostly for women. Many job-matching companies allow jobseekers to have real-time information on vacancies, while helping employers extend recruitment systems to entry-level and low-skill jobs. Voice messages are particularly useful for recruiting jobseekers who have difficulty in reading and writing.

NEW BUSINESS SERVICES

With the extension of the Internet to households it has become possible for individuals to provide business-process services from their homes. This often involves specialised white-collar skills such as computer programming, copywriting and back-office legal tasks. These tasks, generally from firms in developed countries, are carried out by people in such developing countries as Bangladesh, India and the Philippines.

Much of this business is mediated by companies that coordinate freelancers with small and medium-sized firms that require business services. Coordination companies collect a commission from the freelancer, but often charge no fee to those offering the jobs. Most of this work has been done in urban areas, but there are now efforts to extend the opportunities to more deprived areas through “impact sourcing.” This would create potential for more rural employment.

THE SHARING ECONOMY

Another emerging trend with the potential to reshape work is the sharing economy. It is now also possible to match demand and supply peer-to-peer. Alternatives to taxis allow people to use their own cars to provide ride services, blurring the distinction between professional drivers and those who have a spare seat in their private car. Technology is also allowing traditional taxi drivers to work more efficiently finding customers via online services such as Uber, Careem, which operates in the Middle East or GrabTaxi, which operates in several countries in South-East Asia. The same principle is being used by auto-rickshaw drivers in India via mGaadi. Other companies allow people to rent out accommodation in their private homes (such as Airbnb).

These arrangements allow people to make better use of capital assets such as cars or homes. But they can also replace more traditional jobs if they compete with conventional hotels and transport services, such as taxi drivers and hotel staff, who are generally low skilled and poorly paid. There are also new challenges to regulating services, ensuring consistent quality and protecting consumers. In some ways the professionalisation of work is reversing.

START-UPS

Digital technology has made it easier to start a business, an attractive option for young people, some of whom are leaving fairly prestigious jobs to do just that. When individuals have identified a good idea in the course of their work and want to pursue it on their own, they have more tools at their disposal to support their entrepreneurial efforts. Indeed, with over USD 140 billion invested, global investments in start-ups hit a 10-year high in 2017. A recent estimate indicates that in countries with 73 percent of the world's population, there are over 450 million entrepreneurs today, up from 400 million in 2011.

These (often young) people see entrepreneurship a viable alternative to traditional jobs and as a means to pursue their dreams. Start-ups are taking root in both developed and developing countries. Asia is embracing them quite rapidly. Young people see a lot of opportunities there, bolstered by financial technology and big data. Yet start-ups face challenges. Access to capital is one, ideas that are sustainable another. In developing countries weaker legal institutions pose a problem. And long-term viability is their largest challenge.

TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION: JOB GAINS OR LOSSES?

Some fear job losses through automation. Indeed, many jobs are already disappearing, e.g. the work of telemarketers, order clerks, loan officers, photographic process workers, etc. Broad swatches of middle management risk being eliminated. Some estimates indicate that by 2025, almost 50 percent of today's occupations could become redundant.

But other argue that because of technological revolution and the changing nature of the economy, new activities would emerge. And computers are far from being able to use creativity, intuitions, persuasion and imaginative problem solving—in a nutshell, human ingenuity. New jobs will require creativity, intelligence, social skills and the ability to exploit AI. Some argue that for “children who have not been born yet, jobs have not been created yet.”

There has never been a better time to be a worker with special skills and the right education, because these people can use technology to create and capture value. But there has never been a worse time to be a worker with only ordinary skills and abilities, because computers, robotics and digital technologies are acquiring those skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate.

The digital economy and the Fourth Industrial Revolution bring the most apparent changes in our current lives. Fast-paced digital innovations have created unprecedented opportunities for enhancing human capabilities and harnessing human capital across the globe. But at the same time, there are risks in terms of work and workers through unintended consequences of technological revolution. It is a question of balance between opportunities and risks. Furthermore, there will be winners and losers from the phenomenon and that would be a crucial driver of inequalities in a society.

Technological revolution is neither passive nor benign, when it comes to having impacts on work and workers. It would require managing the process through strategies, policies and institutions, bot nationally and globally, in a balanced way so that the benefits are optimised in human lives. The role of policy in equalising the life chances of people to have decent work has never been more important.

Selim Jahan is Director, Human Development Report Office, UNDP.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments