We Are the City

I dream of a city where turning the corner of an alley, in front of a shop of curios and old books, I decide what I want to do for the rest of my life. As I gaze upon the street, on whose brick paved surface millions have walked on, I hear the hum of stories. Cities are millions of stories. Walking, I see signs that the city is both monumental and ephemeral, and elusive yet irresistible. I sense that even if there is no there there, there is a here where I stand: I am the city.

In Italo Calvino's beguiling book Invisible Cities, when the Kublai Khan and Marco Polo exchange stories of places, I understand the city as an existential theater of actions, practices, dreams and imaginations. Our actions, practices, dreams and imaginations. A city is neither hell nor heaven; we make cities in the shadow of our selves. We are the city.

One cannot proceed into the heart of a city without a mytho-poeitic imagination. A city is not mere buildings, streets and spaces; it is, first and foremost, an idea in which buildings, streets and spaces play key part. In considering Dhaka as the toughest city in the world, the challenge is not one of solving energy, transport and infrastructure crises, but in producing the idea of how one should live as a collective. People do not arrive at the gate of a city with just an economic impetus; they come with an image of the city, with an idea of how to be part of that collective.

A narrative of cities cannot be contained only by techno-functional notions around urbanisation and economy. Talks of urbanisation distract the discourse of cities with number games, not taking into account that a city is shaped, bit by bit, not only by policies and ordinances but imaginations and practices. Statistics do not show how a city can be designed and lived in its fullest human, social, aesthetical and ecological potential, a dynamic that is approached best by the term "urbanism." A city is about material and spatial facts, and urbanism is about social relations staged there. I dream I live in a Dhaka for a "total experience of life," where the antagonism between the city and the landscape is not brutal, where the cliched opposition between city and village has been overcome, where wide sailed boats ply in the heart of a downtown, and when the waters come from the mountains where people do not escape to the roofs of their huts but embrace the bounties of the delta. And, where, in the ideal of master architect Muzharul Islam, there are no signs of "haves" and "have-nots." I dream that such a Dhaka is possible.

The city we need

The cities that we have are no longer functional for the age we live in. We now need to talk about the cities we need.

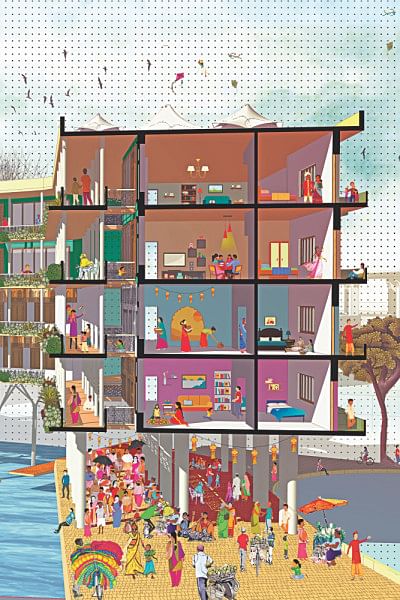

We need cities that have generous public spaces for all, and by all we specially mean women and children; we need housing for all, with building types that fit our culture; we need an intimate relation with rivers as all towns in Bangladesh hug a river or two; we need to give honest attention to public transport; we need to advance walkability and not the demands of the motor car. Above all, we need cities with good governance and decisive actions. About these needs, there should not be any negotiation.

But what is far more important, but ironically vague is our imagination of the city. If Dhaka as a megacity is a pinnacle in our urban thinking, business as usual will not work to make things better. If we-are-the-city depends on how we perceive it, we need a revised imagination for Dhaka.

Cities matter more than ever. Half the world's population now live in cities, making the earth an urban planet. Cities are certainly giant economic engines. Often at par with national numbers, big cities contribute bigly to the GDP. Cities are also the biggest affront to global climate change. In short, cities have acquired incredible complexities.

For hundreds of centuries, humans have defined themselves and organised social life in the parameters of the city. But it has often experienced powerful transformations. The most radical change to the city in its entire history has come with the Industrial Revolution, leading to the profusion of factories as well as shabby housing. It is the dire health condition of those housing, in cities like London and Manchester, that led to the modern urban planning in the 19th century.

The electronic and digital revolution has brought in another dynamic change. In the 1980s, an euphoria over electronic communication (internet) prophesised the death of cities. It was assumed that since people and businesses can be located anywhere, there is no need for the dense fabric or infrastructure of the city. In fact, the reverse is now true. Physical proximity and density are still desirable, both socially and economically. With density, there is greater advantage in digital and entrepreneurial experience of the city, as with Uber, Pathao, food delivery, traffic alerts, etc. At the same time, with increased surveillance, there is a price to pay.

We produce the city

An unprecedented urban phenomenon is opening up a new conceptual and political scope of the city. It is also challenging the dominance of the nation-state as the unilateral spatial container of our experiences. With Venice voting recently to secede from Italy, and Hong Kong struggling with China, territorial boundaries of the nation are being redefined, and spatial obligations rearranged. In the wake of the global refugee phenomenon, the practice of a "sanctuary city" is becoming more and more critical. Upholding this practice, a number of US cities have challenged Trump's federal sanctions against refugees. In his proposal to see Paris as a "city of refuge" in the ancient theme of a "place of hospitality" for those who arrive there, Jacques Derrida offers the vision of a congenial city against the nation-state's adversariality. The German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer's argument for a "post-national constellation" as an antidote to nationism is becoming more ethically imperative today.

Cities can be the most beautiful collective dream, as the urban wizard Jaime Lerner claims. Rejecting the notion that the city is a problem, Lerner insists that cities instead are solutions to our need for collective existence. In transforming the Brazilian city Curitiba as its mayor, Lerner proved that the city is not defined by smog, crisis and deluge but how we should live as a decent society in which the fruits of urbanism are available to all citizens. More recently, another South American city—Medellin—for long a poster child of a city gone terribly awry (drug, murder and mayhem!) has shown that meaningful changes can happen through "visionary leadership, tough politics, and experimental urban design" (Alex Warnock-Smith, Architectural Review, 2014).

A point for our city leaders: We need catalytical examples!

Many urban scholars, from Lewis Mumford to Henri Lefebvre, have articulated the city as an art, that is, a production. "The city," to Lefebvre, "is an oeuvre, closer to a work of art than to a simple material product. If there is production of the city, and social relations in the city, it is a production and reproduction of human beings by human beings, rather than a production of objects." As an oeuvre, a French word denoting an ensemble of distinctive work in art, music or literature, the city is contrasted with the "exchange" value that money and commerce generate. The city above all has "use" value such that streets and spaces, and edifices and monuments, have the preeminent purpose of being used or consumed "unproductively," something that may not be estimated through monetary value alone.

The idea of Dhaka

As incubators of our futures, cities are not simple manifestation of social formation, but prognosis for emerging social and cultural forms. Whether delirious or dubious, there is a new city in the horizon even if its contour remains largely unmapped. While the fabric of Euro-American cities remains mostly stable (or, in some cases, dwindling, like Detroit), migratory dynamic and entrepreneurial and predatory economics are fast changing the Asian urban landscape. Dhaka is a prime example.

From the deluge of the late 1980s to the unforgettable tragedy of Rana Plaza, Dhaka can be easily written off as an evidence of an apocalyptic city-site. Blood springs from the pillars of a garment factory, a tattered shirt is all that remain of a young man who toiled in a stitching section, a delicate foot of a young woman protrudes between slammed slabs, the sad anklet on her foot a sign of a thwarted hope. Such is the landscape of an unruly industrial globalisation.

Borne of the bewildering dynamic of the Bengal delta, people for centuries have learned to live with the extremism of nature that has tested their mettle, creativity and fortitude. The people of the delta, however, do not know how to live with collapsing and burning buildings, of which they do not have any collective memory or folk knowledge. This is the dark side of urban development, the conundrum of magical economic growth and consumer capitalism that is fundamentally entwined with big cities.

Death in the plaza is also a consequence of Dhaka's irresponsible planning, part of an abysmal failure to establish what should be built where and how. Along the way to Gazipur in the north of the city, on the riverbanks towards Naryanganj, and on the road past Savar, concrete and steel rods replace the vernacular of bamboo and thatch. Multi-storied buildings—six to ten-story high—hum with the music of a far-off Gap or Walmart. Freshly laid sand-beds announce the arrival of an upcoming housing society. The transformation of Dhaka and its regions, along with its physical and social landscape, has been relentless and brutal. When an agricultural milieu at the fringe of the city rapidly transforms into a hodge-podge urbanisation, strange things will happen. Nalas, dobas and pukurs—the lowlands—will get filled to shore up tottering towers, without any basic recourse to safety and buildability, and petit goons with the blessings of political leaders will become crorepatis, and enter the mystical chain of globalisation.

By creating landfill after landfill, emaciating rivers and canals, and decimating flood-plains and agriculture, Dhaka makes for a perfect image of an urbanisation without urbanism. But it is in this conundrum, a new narrative of Dhaka is being composed. Even if dubbed the worst city to live in and the toughest city in the world, we are already in an unprecedented urban dynamic.

A new imagination

Bengalis have an ambivalent relationship with cities. Poets and writers sing the sweet songs of villages and versify the vileness of the city. Even when they live and enjoy the city, they dream of the little village through Poet Jasimuddin's comforting image of salubrious vegetation and that untranslatable sense of being wrapped in "maya-momota." Apu, in Satyajit Ray's filmic Pather Panchali, sits redolent amongst a grimy neighbourhood in Kolkata, playing the flute like a Krishna dislocated from his arboreal habitat. Ashis Nandy talks of the troublesome oscillation between the village and the city in the course of which both emerge dystopic. Yet, the city thrives in its cantankerous ways. Thousands arrive at its shore, suffering the insufferable, and not giving up the promises of an upcoming destiny.

Dhaka's primary urban crisis is one of imagination, of not being able to think of the form of an appropriate city even when there are inspiring clues.

Louis Kahn's designs for the Capital Complex at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar are known far and wide, but primarily as examples of a high architecture. Few people recognise that Kahn thought through and demonstrated what a tropical city might look like in the form of a civic forum. The Complex is not only about the stunning architecture but the way varieties of buildings, parks, gardens, orchards, and lakes are arranged in a kind of garden city to form a place of well-being. In an analogical way, Kahn's design continues to invoke the idea that a properly planned Dhaka can be a model tropical city.

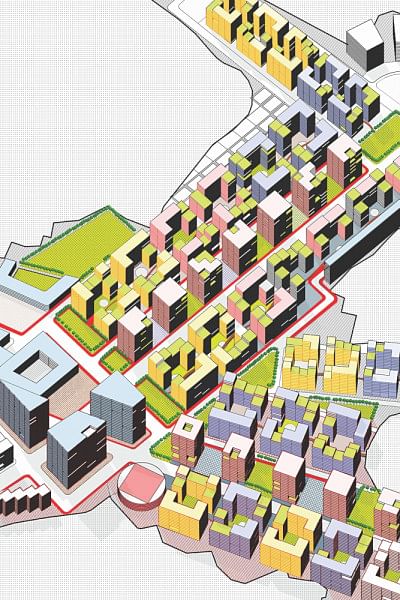

An urbanism for Dhaka has to be conceptualised from the hydrological property of the delta. The theoretical challenge is this: To conceive an urbanism that embraces the inevitable aquatic milieu. Surrounded and infiltrated by a labyrinthine and delicate network of rivers and canals, tissues of wetlands and floodplains, and organic formations of mounds and settlements, Dhaka needs a new approach to city-thinking that generates an aqueous urbanism. One aspect of it is a revision of the city's edge.

The edge is the new centre

The famed Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas talks about the notion of the "edge" in his cartography of the contemporary city. But where the Dutch urbanist meant the fringes of the Euro-American city defined by a frazzled fabric of a post-industrial condition or the tattered terrain of suburbia, a place like Dhaka confronts the edge as the new "centre."

Most urban planners and policy-makers focus on the core or centre city. Even when they are dealing with the edge, they see it in the image of the core. Official planning is unable to conceptualise this edge, to recognise that the edge is its own critical geography. Without that realisation it is easy to participate in the destruction of that landscape. An audacious vision for Dhaka has to begin from the edge that meets the precious landscape of wetlands and agricultural terrains. In short, the norm of planning for Dhaka by thinking from the core has to be reversed. This is valid for planning any town in the delta.

The geography of the edge is determined by the built-city marching up to meet the "non-urban," a magnificent but precious terrain of land-water mass made of wetlands, flood-plains, canals, and agricultural fields. The edge is where the dry meets the wet, the "developed" meets the "primitive," and infrastructure meets the structure-less. This is also where the urbanite meets the farmer, the land grabber discovers his opportunity, and the uprooted makes her habitation. Site/s of the biggest battle in the city, the terrain of the edge is determined by the presence and flux of water. No planning scheme will work for Dhaka if this simple equation is not recognised. It is a battle because it is in that terrain the instruments of landfill and speculations are in play. A new imagination and creativity are needed to address this phenomenon in which neither the stilted ecological ethos of DAP (Detailed Area Plan) nor the aggressive pragmatics of developers has risen to the task.

Nothing short of imagining a new city-form will offer a salvation for Dhaka. The edge conditions of Dhaka present the possibility of re-negotiating the social and economic, as well conceptual, separation between city and its conventional anti-thesis, whether the village or agricultural plains. The edge is where new forms of space organisation in response to a fluxed landscape will have to be reorganised, along with newer forms of economic and social opportunities. It is there, at the edge, a new contour of the city will rise.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and heads the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements. Part of the article appeared in "Making Cities," Jamini International Art Quarterly (2010).

All images for this article were produced by associates at Bengal Institute.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments