Our attitude towards heritage

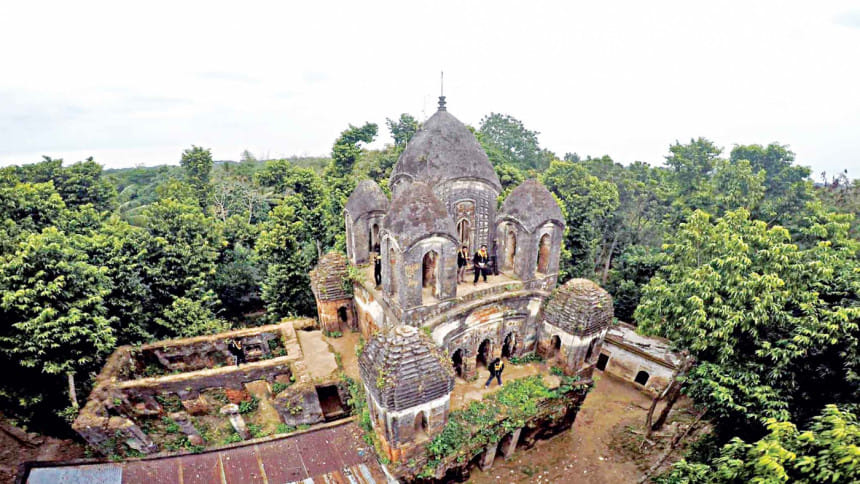

The history of this land is obviously not just 50 years old. It goes back much deeper than that; a long, complicated, and fascinating journey throughout several centuries, because of which, we have today a rich plethora of tangible and intangible heritages as testaments to that journey. Nevertheless, standing at a pivotal year where we celebrate the golden jubilee of independent Bangladesh, it is befitting to ask ourselves of how proud and interested we are about our past.

What is our general attitude towards heritage?

Let's start on a positive note. One may argue that there has been a spike in enthusiasm regarding history and heritage among general people. At least two indications point to that: the popularity of history-based Facebook pages on one hand, and a surge in heritage tourism on the other.

There are a few Facebook groups dedicated to the heritage and history of Bangladesh, and those pages are very active, judging from 'likes,' shares, and comments. Be it a vintage print ad, an old photograph of a street still in existence, or a current photo of an archaeological site, the pages enjoy much audience engagement.

Save the Heritages of Bangladesh is one such Facebook page. Architect and academician Sazzadur Rasheed, the figurehead and one of the admins of the group, have seen a surge in interest regarding history.

He said, "Our page has a huge body of photographic albums on places of historical interest. And having travelled extensively all over Bangladesh, personally and also with our group, I was rather satisfied that we must have covered more or less all the heritage sites of our country. But more recently, some of our group members — hailing from different cities, small towns, and even remote areas — are clicking pictures of their local heritages and sharing them on the group. When I see some of these pictures, I get pleasantly surprised because even after so much travelling and exploring, I find that there are still some sites I am unaware of!"

This not only reflects an appreciation for heritage among people, but also that this appreciation is not limited to people of larger cities; it is arguably nationwide.

This enthusiasm also did not go unnoticed by Adnan M S Fakir, founder of Finding Bangladesh, a team which has made two documentary films (Finding Bangladesh and its second installation) featuring folklores, mythologies, and cultural and architectural heritages.

Talking about their ongoing heritage-related competition Find Your Bangladesh, where in the preliminary stage, applicants had to submit a proposal on a historically important site of their choice — identifying any legends or mythologies involved, and coming up with ideas on how to protect the site — Fakir pointed out that a huge bulk of the teams that registered for the challenge actually hails from smaller towns.

Back to Save the Heritages of Bangladesh, the team also undertakes monthly excursions as a group (although tours have been off since the pandemic hit). And hence, this is not just an online page, but a group with a heritage tourism aspect to it as well.

"Those who register for our trips are usually very enthusiastic about heritage. Most of them do not sign up simply to go on a picnic; they are genuinely keen about history," Rasheed informed.

An organisation which has seen heritage tourism grow over the years, particularly in Dhaka, is Urban Study Group (USG), which campaigns for the protection and conservation of architectural heritages of the city.

In order to raise awareness among locals and foreigners, the institution started to organise 'heritage walks' in the streets and alleys of Old Dhaka around 15 years ago.

"When we began, such walks were scarce. But today, you will find plenty of groups or organisations offering these tours," said Taimur Islam, CEO, USG.

The concept of 'heritage home' has emerged in more recent times. For those who don't know, a 'heritage home' basically refers to an old building of antiquity, where residents offer visits and a meal.

These are not restaurants! After booking in advance, the families will host you, give a tour of their house, and passionately talk about their heritage and share the history of their neighbourhood and Puran Dhaka at large. "Currently, there are only a small number of heritage homes, and we wish more will come up," Taimur commented.

All these initiatives point to the right direction towards understanding, appreciating, and protecting our heritage, and indeed the general awareness level among people is arguably growing.

Take for example the reactions that came out after we discovered the authorities' plans to replace the historic TSC building of Dhaka University with a new multi-storied one, or when we heard similar reports surrounding the iconic Kamalapur railway station.

People were enraged and they vocalised their concerns.

Having said that, this very phenomenon of even toying with the idea of demolition of such significant buildings brings us to another issue: what does this tell us about the attitude of the government and the concerned authorities about the country's heritage?

So far, we have only scratched the surface on the attitude towards our legacies. Dig deeper and soon enough, you will stumble upon a Pandora's Box or two!

To illustrate, there have been several conservation/restoration/maintenance projects undertaken throughout the country that are rather questionable.

The notion of heritage conservation has not yet matured in our country, Taimur opined.

He added that buildings go through an aging process over time; it weathers and the plasters and colours are affected,

and all these give an old look to the building. In conservation discipline, dealing with such aspects are very important and delicate — respecting the structure as it was in its original form in terms of construction techniques whilst keeping in mind its antiquity and aesthetics.

Hence, for restoration, Taimur warns, "There is a fine line. If you cross that line, the building becomes absolutely new."

Anyone who has travelled quite a bit across Bangladesh must have seen — at least once or twice if not more — an old building which has been repainted with obnoxious, bright colours. That's quite a shame!

Even more shameful are entire demolitions of such buildings. Taimur understands the complexity of the whole dynamics that goes behind such activities in the old part of the capital. He mentions some of them: potential financial gains of property owners if they can get rid of an old building and have something in place of that which is commercially more prosperous, monetary incentives given to local leaders and 'muscle men' who are thus willing to back it up, and gaining popular support in the eyes of many locals when a new and large modern building replaces an old one as it may be perceived as a sign of positive development.

Sometimes, attitudes and perceptions of locals towards their own heritage is a grey area; it is not a simple black-and-white matter.

The leading Dhaka heritage activist thus advocates for the necessity of working out compensation schemes for owners of heritage-designated properties, because this shall ultimately reduce the motivation behind the wish to get rid of such old buildings.

In order to protect Old Dhaka's edifices of antiquity, we need sustainable business models, plans, and schemes.

But all is not grim. For example, the heritage activist — who often petitions and appeals to the court on heritage-related concerns and unscrupulous activities — has found the judiciary body, generally speaking, to hold an overall positive attitude towards protecting Dhaka's heritages.

On the other hand, one aspect of history and heritage, on which Bangladesh lags behind, is research.

Adnan M. S. Fakir, as the director of the Finding Bangladesh films, has experienced this first hand.

The documentary filmmaker said, "When researching for Bangladesher Harano Golpo (a.k.a Finding Bangladesh 2: Tales of the South), we wanted to make an exhaustive list of locations relevant to us and then find out folklores and mythologies related to the sites. But getting in-depth information proved to be very difficult.

"Ideally, there should be an online repository of history for researchers and the general people, including a proper catalogue of heritage sites," he said.

The team of Finding Bangladesh deals with the youth, with initiatives such as the aforementioned competition. They also make campus visits for movie screenings, talks, and workshops.

"We need to make history appealing to young people. In schools, history is often considered to be a 'dry' subject. Even if you see those signboards that demarcate heritage sites, the information on many of those boards are not very detailed or not written in an interesting way so that people can connect or relate to," Fakir remarked. "The challenge should be to present history and heritage in a fun and interesting manner."

Hence, for example, Finding Bangladesh 2 (which you can watch on Vimeo) uses a lot of animation work for storytelling.

Initiatives by Finding Bangladesh give us hope of making progress in creating awareness.

The wide array of crafts, too, requires attention; they comprise of a huge part of our heritage. In this sphere, National Crafts Council of Bangladesh (NCCB) has taken a number of praise-worthy initiatives and endeavours, such as appealing to World Crafts Council (WCC) to award Sonargaon — the weaving centre of the age-old Jamdani — the label of a 'Craft City,' which was a success.

Chandra Shekhar Shaha, designer and researcher — and an executive member of NCCB — said that such endeavours require multi-faceted support.

"It is not possible for one individual or even one single entity to undertake projects which would help revive or promote crafts," he said.

He exemplified by mentioning that the WCC Craft City campaign was made successful not singlehandedly by NCCB, but also with the collaboration of various sectors and organisations, such as Bengal Foundation, a number of fashion houses, etc. — and most importantly, the relentless efforts of the weavers themselves.

The veteran designer believes that awareness and interest towards heritage crafts and textiles are still low, with mindless innovations and short-termism making matters worse.

"If you want to make people truly understand and get their attention in something, you have to properly present it first," Shaha continued. "Bangladesh has such a rich history of textiles; crafts which are our legacies. Do we have a textile museum, though? No!"

In the 50 years of Bangladesh's existence, when it comes to the broad spectrum of heritage, much has been lost, a lot is under threat, some initiatives have been taken, and some legacies have been protected or revived to an extent. These comprise of a mixed bag that hints towards our attitude regarding heritage: 'the good, the bad, and the ugly,' as the movie title goes!

What will the next 50 years bring?

Shaha looks forward to it. He concludes, "There is no point in playing the blame game. Let's say for the sake of argument, that in the past 50 years, there were only five initiatives taken to preserve and promote heritage. Now, in the next 50 years, can we aim to have, say, at least 10 good initiatives?"

Photo courtesy: Finding Bangladesh

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments