Preserving crafts and artists for the generations

A snow-white, light quilt embroidered all over in neat miniscule run stiches is dotted with floral jasmine motifs in small intervals. The Nakshi Kantha (embroidered quilt) was one of the early works of Hosne Ara. Despite being torn and tattered in many places, the craftsperson has preserved the old, soft kantha with extreme care and love.

"It is not for sale. I just bring it along with me to show people my meticulous labour of love," Hosne Ara says, while running stiches on a new quilt. She adds that it can take up to six years to stich one Nakshi Kantha with motifs of fish, flowers and other intricate designs. And one such kantha can cost about Tk 25,000.

"In many cases it is the women who labour in the background. A woman might dye the yarn, prepare the clay, dry the product or mix the paint, but much of that goes unnoticed. There are many complex tasks that require the involvement of the entire family. Embroidering and stitching the kantha might be things a woman does at her leisure, when all household chores are done and she has some time to herself. For many, the skill they learned from childhood is now their profession, a means to their livelihood," says Luva Nahid Choudhury, Director General of Bengal Foundation. Currently she is also a Vice President (South Asia 2021-2024) of the World Crafts Council Asia Pacific Region.

While a six-figure price for a handcrafted item can seem overwhelmingly high to some, Choudhury believes it is a just and fair price if one pauses to reflect on the skill, creativity and intense labour that goes into making such a product.

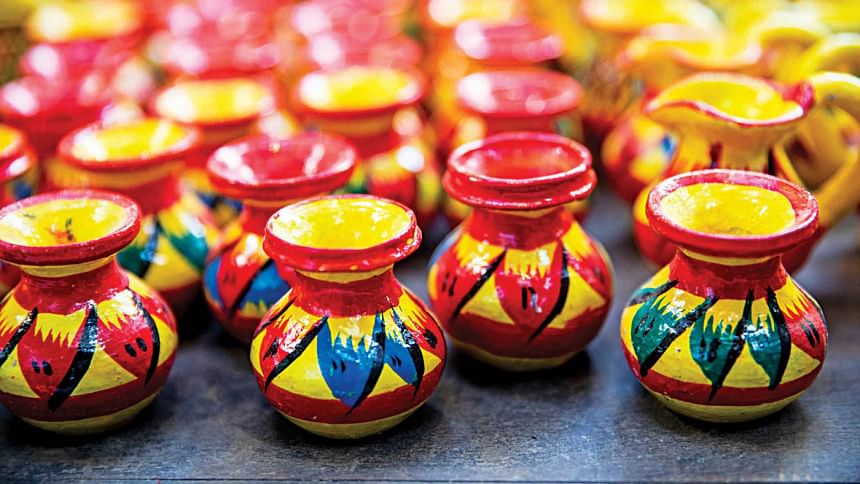

Local jewellery, terracotta figurines, woodwork, Nakshi Kantha, brass or bell metal handicrafts, rickshaw painting, cane, Shitalpati, hathpakha, shell or shonkho, shola, lokkhishora — the list of local crafts is endless. Their beauty and distinctiveness lie in their design, colour choices, weaving skill, motifs and embellishment. Each craft has its own story to tell, in its own unique blueprints and patterns; it also talks of the history of the land where it originates, and how it borrows and evolves.

"Craft has a story that not everyone is interested to know. Local crafts often look brash and cheap for use as decorative household items. Our people in general are attracted to bling; they cannot fully appreciate the vivid colours and rustic look of handcrafted items. I would say only five percent people appreciate the ethnic look of our local crafts," says Shaibal Saha, Fashion and Crafts Design Consultant, Fashion Design Council of Bangladesh.

Exquisite crafts of our land

Shondha Rani was showing her wooden toys with wheels, a typical mustard yellow horse, a tiger with red stripes on it, and an elephant tinted black.

"These are all painted by my husband Ashuthosh Shutradhor and are typical of Sonargaon motifs featuring bright yellow base, adorned with motifs in red, blue, and black," she says.

Like many other heritage crafts of our land, intricate bronze statues, utensils, and pottery bearing folk motifs hardly find a place in our society, amidst the ever-growing urge to (modernise?) urbanise everything around us. Similar is the age-old account of our jewellery.

Designs before and after the partition of 1947 have their own history, and now, a new Bangladeshi aesthetic is influencing the style and designs of jewellery.

Shagorika earring or Manipuri earring pieces were favourites with young women of yesteryears. The longstanding choker or golapbala bangle, shathnuri haar or necklace, bicha or waistbelt, and the ever-beautiful motor haar, shita haar necklaces were the choicest favourites among women.

"The ladies in the village used to wear nolok (mid-nose ring) with motifs of a rice grain and makri earrings; these beautiful pieces were influenced by Islamic designs. The better off among them wore bracelets, anonto bala, and invariably they all had a mother of pearl pendant with a floral motif overlaid," Saha fondly explains.

Adding that now with globalised style of Jaipuri jewellery in demand, traditional designs are all lost or hardly preferred.

"Our designs didn't evolve. We seem to be more into jewellery from Dubai, India, Pakistan. And unfortunately, there is no documentation or research based on which we can revive the designs. With the lack of demand, we have even forgotten the beautiful terms each piece was named after," Saha says.

Commenting on the need to restore prestige to the handmade product and consolidate the position of craftsperson in society, Luva Nahid Choudhury says, "The production of crafts is linked to livelihood and trade, and hence, craft too has to evolve with the times. However, it is important to be able to understand those intrinsic qualities that lend a product its high value, appreciate the wisdom handed down from generations that underpin creativity, and be able to differentiate between indiscriminate adaptations and well-researched, informed innovation.

Of fairs and commissioned workshops

The handicrafts industry should be incentivised, and at times subsidised, as many craftsperson belong to a vulnerable stratum of the society. They are subject to ecological shocks, market shifts and marginalisation.

The COVID pandemic has depleted the crafts community's capital. Left with no earnings, many have moved away from their trade and resorted to alternative means of employment, such as vending vegetables or working as day labourers. The drain of skilled hands is likely to deplete the crafts sector and will limit its resilience and ability to rebound.

"Many successful RMG businesses have invested in high quality local clothing brands. This has given the local fashion industry a boost and created a competitive edge. These brands are perfectly poised to collaborate with the country's crafts sector. I would like to underscore a bottom-up collaborative approach with master craftsperson, instead of a top-down instructional approach, which will hopefully lead to well thought out choices in innovation and product diversity. By taking this route, it may also be possible to connect high quality Bangladeshi crafts to international couture," Luva Nahid Choudhury feels.

Designers who have international presence need to come forward. The process of engaging with master craftsperson will not produce results overnight. It will require investment, a longer perspective and most of all, commitment to the cause. Workshops, design studios and spaces for sharing knowledge and technical know-how need to emerge.

"The Jamdani Festival organised by the National Crafts Council of Bangladesh and Bengal Foundation in 2019 did very well as it received much regional and international attention. Such an exposition is useful in reminding ourselves about the high degree of craftsmanship the weavers are capable of and how incredibly resilient they are. Collaborations between master craftsperson and designers who have an understanding of and empathy for handmade goods, will enable us to carve out a space for responsible fashion," she explains.

Some terracotta crafts, cane, bamboo, jute, and water hyacinth products have found their place in the export market but questions remain about their quality. However, fine and niche products like those made of shola, the soft white pith of a spongey plant, which are an integral part of Puja and Hindu weddings, or crafts from shonkho or shell, are losing their way amid changing tastes and the maze of urbanisation.

One might still find traces of such products in big fairs like the Zainul Mela, but the associated craft is fading out for lack of documentation, incentivisation and governmental subsidy. The crafts sector will benefit from greater collaboration between the National Crafts Council of Bangladesh and government agencies.

Initiatives such as the Karu Kotha exhibition at Bengal Shilpalay and Zainul Mela at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka, create opportunities for the public to gain an understanding of the value of handmade products. In the flurry of becoming 'modern' and the slew of cheap, imported goods in the market, younger audiences comprising new executives, college students and home workers are often unaware of the importance of handmade products. Fairs and expositions play an important part in providing an opportunity for the uninitiated to learn about the crafts heritage of our country.

The end story

Apart from exceptional high-quality crafts, it is the nature of handmade products that they are rustic, simple and unpolished. Yet, they have the power to connect to our inner selves. Nowadays, when there is a great deal of concern about ecological balance and seeking a sustainable future, handmade products can lead the way. Craftsperson, now more than ever, need help to preserve their skill and ensure cultural continuity, and be able to live justly by their craft.

Photo: Sazzad Ibne Sayed

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments