How Ekushey was commemorated during the Pakistan period

The Language Movement began in the immediate aftermath of the establishment of Pakistan, spurred by the demands of student organisations in the then East Pakistan. It was a crucial component of a broader set of demands addressing the realities of East Pakistan. The events of February 21 marked the culmination of the Language Movement—termed a language controversy by the then government—which had its roots in the late-1947 to early-1948 period. Historians in East Bengal typically distinguish between the events of 1947-48 and 1952 based on their reach, impact, and underlying causes. The first phase of the Language Movement was initially galvanised by the demand for Bangla to be the language of procedures in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan by Dhirendranath Datta, and by Jinnah's unequivocal declaration at Dhaka's Race Course Ground that "Urdu and only Urdu shall be the state language of Pakistan,". The second phase gained momentum following then Pakistan Prime Minister Khwaja Nazimuddin's statement in the last week of January 1952, affirming that only Urdu would be the state language of Pakistan.

Until 1952, student organisations in East Bengal observed March 11 as the "protest day" throughout the province to commemorate the fact that on this day in 1948, for the first time, hartal was observed demanding Bangla as a state language. The police firing on the protesters in Dhaka on February 21, 1952, and the killings of Barkat, Rafique, Jabbar, and others took that demand to such a critical height that, despite reluctance on the part of Pakistan's ruling class, Bangla's status as a state language of Pakistan was ascertained. Therefore, we see in the 1956 constitution of Pakistan that Bangla was acknowledged, and again in the 1962 constitution under Ayub Khan's rule.

" layout="left"]In addition to establishing Bangla as a state language of Pakistan alongside Urdu, the martyrdom on February 21 instilled an unprecedented emotion in the psyche of the younger generation in East Pakistan. The immediate outpouring of poems, stories, songs, and publications, as well as the construction of hundreds of monuments at educational institutions throughout the province were a testament of this emotion. The cultural and literary flourishing in East Bengal was not only a result of the Language Movement but, more significantly, of the events of February 1952.

Since 1952, February 21 has become an inevitable component of the social, cultural and political life of East Bengal. The day has been observed as Shaheed Dibosh or Martyrs' Day throughout East Pakistan. A demand was raised from different quarters for declaring February 21 a public holiday. The significance of the demand can be discerned from the fact that it was one of the demands of the 21-Point Programme of the United Front.

The commemoration of February 21 as Shaheed Dibosh met with strong opposition from the government as the latter deemed such observation antithetical to the national unity of Pakistan. That is why the first Shaheed Minar (monument of martyrs), erected on February 23, 1952, was razed to the ground just four days later by the police and military amid a crackdown on the protesters—through arrests, police warrants and harassment by law enforcers. For instance, in 1955, five students of Dhaka University were arrested for being involved with the observance of February 21.

From the beginning, the remembrance of February 21 reflected the political reality of Pakistan, not least the province of East Pakistan, and the mood of popular demands. The United Front government under AK Fazlul Haq did not last long enough to actualise the promise of making February 21 a public holiday. Later on, on February 16, 1956, the United Front government declared the day "Martyrs' Day". It was declared a provincial holiday as well. The formation of the United Front government and the recognition of Bangla as one of Pakistan's state languages by the constitution in 1956 led to a leniency by the government towards the observance of the day to some extent. Barefoot morning procession to the Shaheed Minar with flowers, chanting slogans in support of political, cultural, and economic demands, prayers at the graves of the martyrs, and organisation of seminars—all these were parts of the observance of February 21.

The introduction of martial law and the imposition of a ban on political activities, as well as public processions and meetings, temporarily made the commemoration of February 21 difficult. Despite the strict martial law, students and cultural activists continued to observe the day as usual, though the authorities of schools and colleges displayed ambivalence.

From the beginning, the remembrance of February 21 reflected the political reality of Pakistan, not least the province of East Pakistan, and the mood of popular demands. The United Front government under AK Fazlul Haq did not last long enough to actualise the promise of making February 21 a public holiday. Later on, on February 16, 1956, the United Front government declared the day "Martyrs' Day". It was declared a provincial holiday as well.

However, the 1960s marked the resurgence of political movements in East Pakistan. Lifting the ban on political activities and the recognition of Bangla as a state language in the 1962 constitution once again eased the official mode of celebrating February 21. Most importantly, there was an acceleration of democratic movements, including that of students, workers, and peasants, during this decade that was organically linked with commemorating Ekushey.

Prabhat Pheri, cultural activities, seminars, and prayers continued to be held as before. Newspapers earnestly published special issues on February 21. On this day, as protesters renewed their vows to restore democracy and the rights of the people of East Pakistan, progressive and pro-Bangla newspapers published editorials emphasising the significance of the day and paying homage to the martyrs.

In their editorial commentaries, newspapers like Ittefaq and Sangbad sometimes juxtaposed the self-aggrandising and ambivalent nature of contemporary Bangla politicians with the courage and ultimate sacrifice of the martyrs of February 21.

Pakistani nationalists and the dailies that adhered to the government line, too, commemorated the day with due importance. It will not be irrelevant to mention that such dailies usually portrayed the establishment of Bangla as an official language of Pakistan as concomitant to the establishment of Pakistan. They also put emphasis on the importance of creating a different Bangla than West Bengal. During the autocratic rule of Ayub Khan, the question of establishing the honour of the mother tongue Bangla and implementation of Bangla in every sphere of life became a trope in the commemoration of the Language Movement in the 1960s. Professor Anisuzzaman, in an essay written in the mid-1960s, mentioned that one aspect of the Language Movement had been realised, but the spirit needed to be carried on.

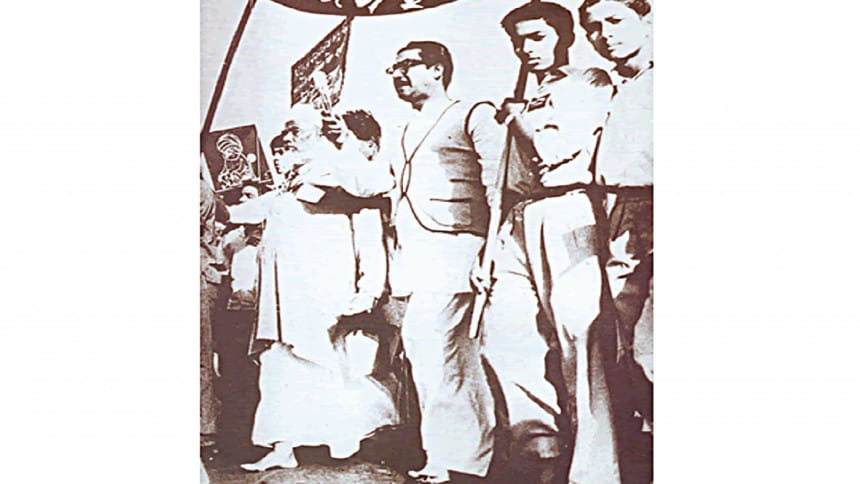

The last three occasions of February 21 under united Pakistan were especially significant in honing the spirit of protest and defiance. The Shaheed Dibosh or Amar Ekushey of 1969 was celebrated amid the anti-Ayub mass movements in East Pakistan, breaking all government prohibitions. The provincial capital saw hundreds of thousands of people marching towards the Shaheed Minar. Shamsur Rahman in his poem "February 1969" wrote about people from every walk of life came to the Shaheed Minar:

I am a weary farmer from the distant Palash Toli,

Like a worn-out canvas from the medieval era,

I am a boatman in the River Meghna, the constant companion of monsoon clouds and stormy winds,

I am a labourer in the jute mill,

I am the pupil of the eyes of the deceased Ramakanto Kamar,

I am the melancholy potter of the paved yard,

A silent witness to the desolation of the nearly abandoned village,

I am a weaver without a loom … weaving thick and intricate fabrics,

Blending friendship in the rhythm of the loom,

I am a pitiful clerk of the revenue office, snubbed and burdened with too many dependents

I am a student, a bright youth,

I am a budding writer of modern times.

Not only in Dhaka, but also in all other cities, towns, and the countryside, the scenes were reminiscent of February 21, 1969. February 1971 came after the devastating cyclone and the Awami League's victory in the 1970 elections, amid widespread deep-seated rumours and suspicions about the military's willingness to hand over power to the Bangalees.

On February 21, 1971, throughout East Pakistan, from early morning onwards, people started pouring into the Shaheed Minar. Streets, alleys, and by-lanes all became flooded with people raising slogans and singing protest songs, along with Amar Sonar Bangla, the soon-to-be national anthem of Bangladesh. Alongside these activities, people were also collecting funds for the cyclone-affected people of southern Bengal. The day was observed with renewed pledges for upholding the spirit of sacrifice and struggle.

Mohammad Afzalur Rahman is currently pursuing PhD at Jawaharlal Nehru University. He can be reached at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments