Through the lens of Rafiqul Islam

National Professor Rafiqul Islam's profound contribution to documenting the Language Movement in Bangladesh was the culmination of a lifelong passion for photography.

From his early days, Rafiqul was seldom seen without his trusty Kodak 620 box camera, a constant companion in his photographic endeavours. This childhood interest took a significant leap in 1949 when an acquaintance of his returned from Britain and gifted him a German-made Voigtländer camera, equipped with a 4.5 Lanthar lens, having seen Rafiqul's love for photography. Unlike the automatic "Rolleiflex" or "Rolleicord" cameras of the time, this Voigtländer demanded meticulous manual adjustments, covering aspects such as aperture, distance, and timing, which only fuelled Rafiqul's fervour for photography.

This enthusiasm was further fuelled when Rabindra Sangeet singer Kalim Sharafi presented him with a Wide Lux camera, another German masterpiece featuring a 3.5 Colour Skopar lens. Unlike its modern counterparts, this folding camera could only capture eight images before necessitating a roll change. It required a comprehensive manual set-up for each shot, challenging the photographer to meticulously calibrate distance, aperture, and lighting based on personal judgement. Rafiqul embraced this challenge wholeheartedly. Wherever he went, he carried this camera, always prepared with a film roll loaded and an extra one in his pocket, ready to capture moments that would eventually become invaluable historical records of a significant cultural movement.

Growing up in the Railway Quarters located in Dhaka's Ramna area—just behind Fazlul Haq Hall of Dhaka University—gave Rafiqul a unique position to chronicle the historical Language Movement through his photography. It wasn't until the year 1951, around June or July that he enrolled at Dhaka University.

This dual existence, as a Dhaka University student and resident of a close-by area, allowed him an intimate view of the burgeoning movements and struggles that were shaping the region's history—a perspective that few others had. Seizing this opportunity, Rafiqul captured the essence of the times through his lens, photographing processions, assemblies, and the many faces of the movement. What made his photographs unique was that they were captured by someone who was not only a witness but also a participant in the historical narrative of Bangladesh.

Initially, Rafiqul observed the stirrings of the Language Movement as early as 1948, yet he remained a passive observer, not actively engaging in the activities. This changed dramatically in 1952 when, as a student at Dhaka University, he found himself spontaneously drawn into the heart of the movement.

He participated in rallies and meetings, blending his activism with his academic and cultural pursuits at the university. He used his camera, the Voigtländer, as a tool to capture the essence of these events. Between 1952 and 1957, Rafiqul Islam documented many significant moments of this historic period, creating a treasure trove of memorable photographs.

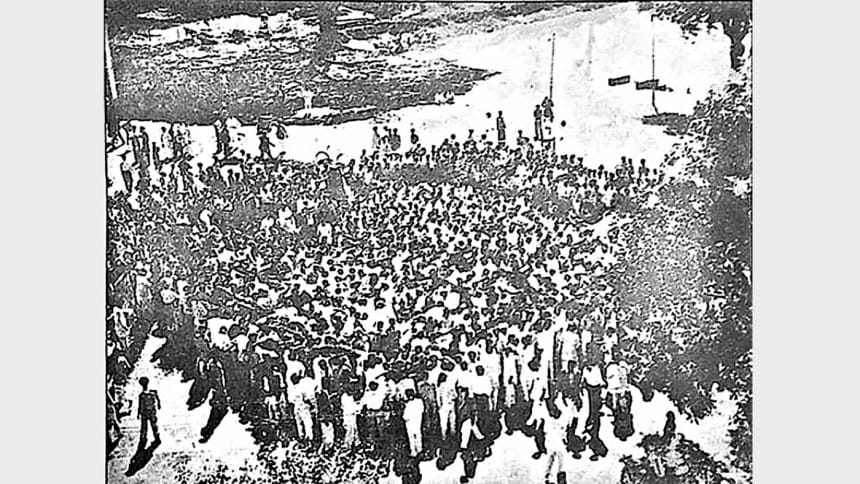

However, his photographic journey took a significant turn following the declaration by Pakistan's Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin on January 27, 1952, announcing Urdu as the sole state language. This announcement sparked widespread protests, including a student's march from Dhaka University. Rafiqul was there, camera in hand, documenting these critical moments. He captured images of the students meeting at Amtala on February 4, the observance of Flag Day on February 11, and the large procession that marked this day.

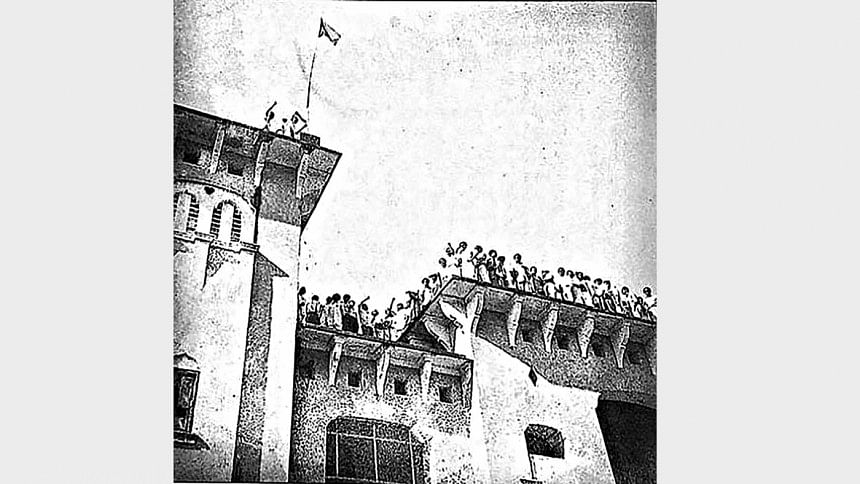

February 21, 1952, however, was a day of crucial significance. As students and the general public began gathering at Amtala from early morning, Rafiqul faced a critical decision: join the groups defying the Section 144 curfew, risking arrest, or document the unfolding events. He chose the latter, though this path, too, was fraught with challenges. In a daring move, he evaded the police and, with the help of friends, climbed onto the roof of the old Arts Building (Kala Bhavan). From this vantage point, he captured a few photographs before descending to continue his discreet photography. Despite the risks, Rafiqul successfully took 16 images, each one capturing a fragment of the historic day, now revered as the International Mother Language Day.

In the afternoon, as police opened fire at the Medical College junction, Rafiqul moved towards the Medical College Hostel. Amidst the ensuing chaos, with students and the public frantically seeking safety, Rafiqul found himself at the main entrance of the Medical College, witnessing a harrowing scene: an ambulance arrived, carrying the body of a victim whose skull had been shattered by a bullet, a gruesome image marked by brain matter and smoke.

At this moment, Rafiqul encountered another photographer, Amanul Haque, and inquired about his film supply. Haque confirmed he had 2-3 films left. It was then that a government journalist, Kazi Mohammad Idris, posed a haunting question, asking if they intended to photograph the newly arrived corpse. They soon learned that the body had been secretly moved to a nearby storage room, rather than the emergency room of Dhaka Medical College Hospital. Amanul Haque, wielding his German Zeiss Ikon camera, captured the photograph of the body, which was identified as Rafiq Uddin Ahmed, the first martyr of the Language Movement, from Paril village in Manikganj. Unfortunately, Rafiqul, having run out of film, missed the chance to document this critical moment.

Realising the importance and sensitivity of the photographs he had already taken at the Amtala assembly and the procession, Rafiqul became deeply concerned about their preservation. With police and intelligence agents swarming the area, he deemed it unsafe to keep the films at home, fearing a potential search. He acted swiftly and decided to take the films to a studio named "Zaidi," located behind the Secretariat. The owner, a non-Bengali, was unaware of the photographs' significance as Rafiqul handed over the films without revealing their content. His caution was justified when he returned home to find two intelligence agents waiting for him. They questioned whether he had taken any photos. Rafiqul handed over his camera, asserting it contained no film. The agents, finding no film inside, eventually left.

The next day, February 22, dawned with a solemn but defiant air. The streets of Dhaka city were filled with thousands of people, undeterred by the Muslim League government's intimidating stance. Among them was Rafiqul Islam, camera in hand, ready to document the unfolding events. Having retrieved the films from the studio the day before, he went to the prayer ground of Dhaka Medical College, where he documented the funeral prayers. He skilfully captured the subsequent procession, adding to his growing collection of historic images.

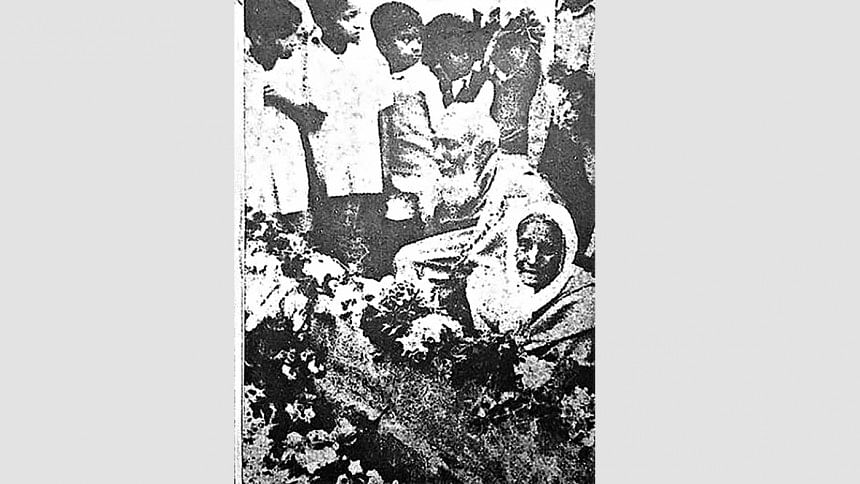

His dedication to chronicling the Language Movement extended to the first Martyr's Day observation on February 21, 1953. He visited the Azimpur graveyard, photographing the graves of Language Martyrs Abul Barkat and Shafiur Rahman, and documented Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani laying wreaths at their graves. His lens also captured the Shaheed Day celebrations in the following years, 1954 and 1955.

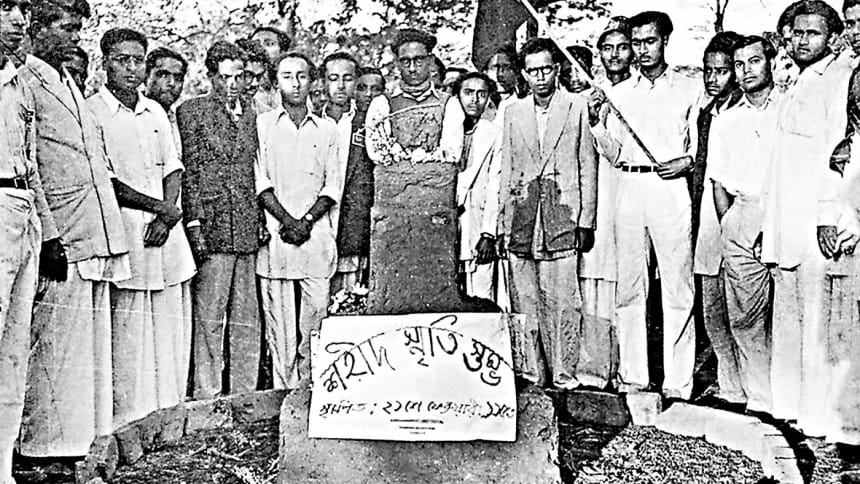

In 1953, the Shaheed Minar was constructed by students of Dhaka College and Eden College. Rafiqul Islam made sure to diligently document the entire construction process of the Shaheed Minar, adding another layer to his comprehensive photographic record.

Despite the significant role his photographs played in immortalising the Language Movement, Rafiqul remained modest about his contributions. In an interview, he once stated, "But I have nothing to brag about. I was there, I had a camera on my shoulder, it had film in it, and I took some pictures of Kala Bhabhan, some from below, some from above. On the following days, 22nd and 23rd, I managed to take a few more pictures."

Rafiqul Islam's photographs have become an invaluable asset in the history of the Language Movement, standing as a living testament to the struggle and sacrifice of those who fought for linguistic justice. Each year, as the world commemorates International Mother Language Day on February 21, his images resurface, offering the most authentic glimpse into the heart of the movement. Rafiqul Islam's name, as long as the Bengali language and the spirit of Ekushey (21st) endure, will continue to be spoken with deep respect and gratitude for his invaluable contribution to preserving this crucial chapter of history.

M Abdul Alim is an educator at Pabna University of Science and Technology

Translated from Bangla by Nazifa Raidah.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments