Are myths and misperceptions influencing policymaking?

Are policies and actions regarding preparing young people for work and livelihood influenced by myths and misperceptions about the problems and their workable solutions?

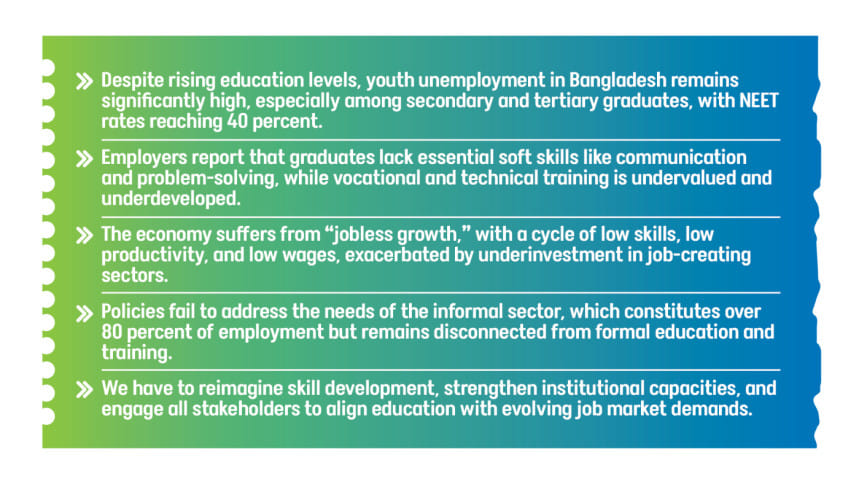

Let's look at some pertinent factual information cited by the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD, 2022). According to the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) 2016-17, unemployment among youth with secondary-level education was a high 28 percent (BBS Labour Force Survey, 2016-17). The unemployment rate among higher education graduates was 32 percent in 2015 and rose to 43 percent by 2017. Another relevant piece of data is that 29.8 percent of youth aged 15-24 were not in education, employment, or training (NEET) (BBS, 2018).

The 2023 Labour Force Survey provides some updated data. The NEET rate has now reached 40 percent. Among young women, the NEET numbers were five times higher than for men. The overall unemployment rate in the 71-million workforce in 2023, in round numbers, was 5 percent, but unemployment for the 15-24 age group was three times higher at 16 percent. The big picture is that young people, that is, new entrants to the labour force, have a significantly higher unemployment rate, and the more educated the job seekers, the higher their unemployment rate.

The higher unemployment rate for completers of secondary and tertiary education is a worldwide phenomenon. Unemployment among educated youth is typically two to three times the rate of total unemployment in the workforce. This is partly due to what is called "frictional unemployment." When one looks for a new job or transitions between jobs, it often entails waiting for a job of one's choice. This happens more often among better-educated youth because they can wait for a preferred job, whereas their poorer and less-educated counterparts cannot afford this luxury. They take any job available to make ends meet.

What about the 40 percent of young people in NEET? There is certainly a large overlap between this category and those in frictional unemployment. But can the problem of unemployment—and more importantly, underemployment, low earnings, and low productivity of workers—be attributed mostly to the quantity and quality of education?

What are the overall educational characteristics of the workforce? The 2023 survey shows that of the 15+ population, 35 percent had primary or lower-level education. Almost half, 46 percent, had attended secondary school, and 9 percent had completed higher secondary. Only 8 percent had pursued tertiary education.

The CPD policy brief suggested that the current educational system does not emphasise technical and vocational skills enough, which may lead to better labour market outcomes, and that education is not equipping youth with the right skill sets to make them employable in the job market (CPD, Skills for Youth Employment: A Policy Perspective, 2022).

The conclusions were drawn from an online survey of 100 potential employers (private sector businesses and NGOs) to determine the soft and hard skills they looked for in employees. Employers highly rated communication skills in English and Bangla; next in order were problem-solving, critical thinking, teamwork, leadership, creativity, and time management. The hard skills they preferred in their employees were computer skills and job-specific knowledge and technical skills.

Some 500 recent graduates from public and private universities were administered a test developed by researchers on the skills noted above. The graduates did poorly in communication, problem-solving, and time management. They performed better in teamwork and leadership, critical thinking, creativity, computer skills, and business skills.

One may wonder how adequate the tests were in assessing the graduates' skills, as soft skills are interconnected. For instance, if one performed well in problem-solving, one is likely to do well in critical thinking and creativity. On the face of it, if graduates show a "skills surplus" by surpassing employer expectations in several areas, as found in the study, one might argue that educational institutions are doing a good job. However, communication skills in English and Bangla, highly rated as a necessary job skill by employers, appear to be a particularly vulnerable area. This situation points to a fundamental weakness at all levels of education, from primary school to university—not just a problem related to preparation for employment and vocational training.

It is often said that employers are not happy with the skill sets of job seekers and cannot find the type of workers they need. The blame for this is placed on education and training institutions. However, policymakers and employers do not ask whether they themselves can do anything about it. We see a prevalence of "jobless economic growth" promoted by economic and investment policies. In Bangladesh and many other developing countries, a kind of stasis or balance of low skills, low productivity, and low income for workers has been reached. These economies are trapped in a cycle of poor productive skills, underemployed workers, and underinvestment in job-promoting economic activities. In these circumstances, merely expanding the current pattern of skill training is not enough. New thinking is needed for qualitative changes in education and training, as well as in macroeconomic policies and investment strategies aimed at job growth and decent incomes for workers.

A major feature of the economy of Bangladesh and other low-income countries is the large relative size of the informal economy—individual or family-owned small-scale economic activities, not bound by government regulations regarding safety, workers' rights, and taxation, and usually employing family members or a small number of other workers. This informal economy accounts for approximately 40 percent of GDP and over 80 percent of employment. Prevailing education and training policies, objectives, and activities, such as those discussed above, do not take into account the employment and skill generation needs of the informal economy.

In Germany, which has a reputation for high-quality vocational skill training, one-third of secondary-level students opt for the vocational education track. Dual vocational training is a well-established feature of secondary education in Germany. It allows students to work as interns on day release or part-time in an industry while pursuing general education in secondary school. A critique of German vocational training noted persistent myths about students in the vocational stream being of lower intellectual calibre, the training leading only to low-paying blue-collar jobs, not opening doors to high-reputation firms, and leading to a dead end for professional advancement and higher education. These, however, are all unfounded myths in Germany. Unfortunately, they are not myths but reality for much of vocational education and training in Bangladesh.

To equip the next generation with the necessary skills and capabilities, it is essential to:

1) Re-examine the nature of the evolving economy, changes in the profiles of skills needed, and reimagine the provisions for skills and their management.

2) Strengthen institutional and organisational capacities to assess the demand and supply of skills and establish a balance and connection between the two.

3) Ensure that all stakeholders, including the private sector, NGOs, and social enterprises, are meaningfully involved in charting the roadmap and moving forward.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments