How are Indigenous people faring in the new Bangladesh?

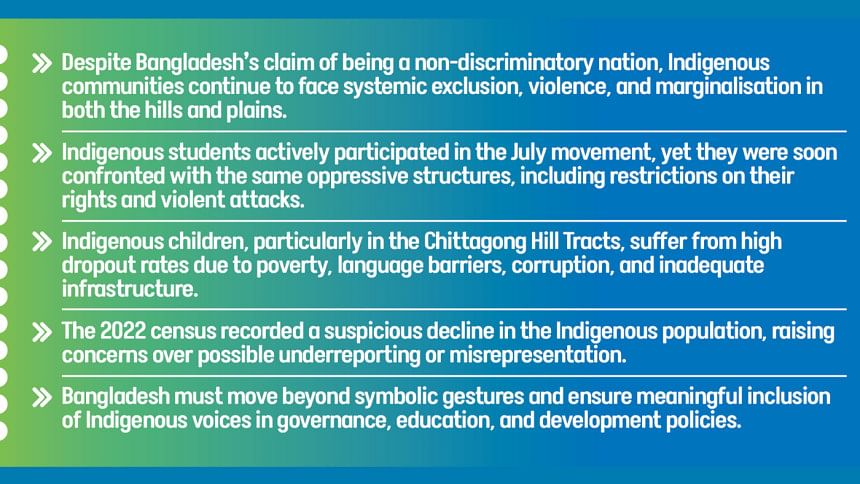

How many people genuinely care about the state of Indigenous communities in the "new Bangladesh," which claims to be free from discrimination? Indigenous students and activists joined the July movement with hope, ambition, and passion. Yet, the events following the fall of the fascist government on August 5 serve as a stark reminder that many people in the country still resist inclusion of Indigenous people.

Due to the discriminatory policies of the Pakistani government, the people of this country fought against injustice and won their freedom in 1971. However, in the very Bangladesh that emerged from that struggle, the constitution was drafted without fully recognising the voices of the hardworking masses, the marginalised labourers, and the diverse ethnic communities.

From the moment of independence, Indigenous and working-class people in Bangladesh have continued to face discrimination. Although the constitution states that "all citizens are equal before the law and entitled to equal protection under it," the reality has been far from equal. These communities have never been viewed through the same lens by the state. Instead, they are often labelled as "lagging behind."

Now, in this new, non-discriminatory Bangladesh, the real question remains: have these people merely fallen behind, or have they been systematically deprived? Even after 53 years of independence, why are they still pushed to the margins, labelled as weak and disadvantaged? The state must answer.

The July uprising claimed thousands of lives, with many more left injured. Yet, despite such immense sacrifice, incidents of violence erupted in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) within just a month. In September, lives were lost in Khagrachari and Rangamati. More than 50 people were injured, over 100 shops were reduced to ashes, and homes were set ablaze, vandalised, and looted. These events deepened the crisis of trust in the hills. The students who had joined the July uprising with dreams of a non-discriminatory Bangladesh were instead confronted with disappointment again.

After the July uprising, when young people across the country were expressing their emotions through graffiti, students in the CHT were denied that right. Not only were they prevented from painting graffiti, but they were also dictated to on what to paint and which slogans to write. These restrictions on hill students make it clear: the spectre of the old fascist government still looms over the hills.

At the time, students voiced their frustration. Shawni Marma questioned, "Students across Bangladesh are drawing graffiti. So why are students in the Chittagong Hill Tracts being discriminated against?" Similarly, Jhumka Chakma expressed concern, saying, "We don't want the hills to be destroyed in the name of development. Has the country's independence only been for the plains? Will we never have freedom in the hills?" (The Daily Star Bangla, August 18, 2024).

If we look at the plains, there have been reports of attacks, looting, vandalism, and arson in at least 20 areas across the northern region since August 5. These incidents occurred in various districts, including Rajshahi, Naogaon, Dinajpur, Thakurgaon, and Chapainawabganj. During this time, the sculpture of Sidhu-Kanu—revered heroes of the anti-British movement in Bengal—was demolished. In addition, houses belonging to the Santal community were set on fire and looted in Pipalla Santal village of Birol upazila, Dinajpur. The Dinajpur district administration acknowledged the vandalism and looting of indigenous homes. However, it remains unclear whether any action has been taken against those responsible.

The latest incident that caused a nationwide uproar occurred on January 15 in the capital, Dhaka. The controversy stemmed from the removal of graffiti drawn by students during the July uprising on the back pages of ninth- and tenth-grade textbooks. The artwork depicted a tree symbolising indigenous identity, and its erasure sparked protests among indigenous students. As they marched towards the National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) in protest, they were brutally attacked by members of the so-called "Students for Sovereignty." Several indigenous students sustained serious injuries.

During the July movement, these Adivasi students had stood shoulder to shoulder with their peers against the oppressive gaze of the then-authoritarian government. Yet, within just six months, some people had already turned against them, embracing fascist tendencies and directing their aggression towards the Adivasi students. This raises an urgent question that we find ourselves asking repeatedly—how have Indigenous people truly fared in this so-called new, non-discriminatory Bangladesh?

Now, let us examine the improvement in the quality of life of Indigenous people. When we talk about development, the first thing that often comes to mind is infrastructure. We tend to equate roads, buildings, and bridges with development. However, does infrastructure alone truly signify the development of a community or an ethnic group?

A closer look at the education system in the CHT reveals a grim reality. The region has the highest student dropout rate at the primary level, ranging between 30 percent and 40 percent, compared to the national dropout rate of 20 percent from primary to secondary education (Prothom Alo, September 2023).

Several factors contribute to this high dropout rate in the CHT, including poverty, poor transportation networks, language barriers, teacher shortages, parental unawareness, and the absenteeism of teachers in remote schools. Moreover, widespread corruption within the hill area's local administration—particularly in the recruitment of primary school teachers—further exacerbates the crisis. Due to corrupt practices, incompetent and underqualified teachers are appointed, depriving primary students of quality education.

This issue is not limited to the hills; a similar situation exists in the plains. Indigenous children across Bangladesh face systemic barriers to education due to poverty, linguistic differences between their native languages and the institutional medium of instruction, limited access to opportunities, and a general lack of awareness. These challenges continue to deprive them of their fundamental right to education.

Before discussing Indigenous development, we must first determine how it should be measured. The Bangladeshi government has been striving to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), yet numerous challenges persist. However, how can these targets be met if a significant portion of the country is left behind?

SDG Goal 4 explicitly calls for ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education. Yet, the nation must first be informed about the government's initiatives to bridge the educational gap in areas such as Sajek in the CHT, Remakri in the remote regions of Thanchi, or among Munda children in Shyamnagar, Satkhira's coastal belt. While discussions about inclusion continue under the current interim government, there is little clarity on how and where inclusion is truly needed.

The Adivasis are once again demanding their inclusion in the constitution. Ironically, many of those now in power under the interim government previously advocated for Indigenous rights and freely used the term "Adivasi." However, even among them, a growing hesitation around the word is now evident. The Awami government deliberately fuelled a misleading debate by redefining Adivasi to mean only Aboriginals. Today, the persistence of this twisted definition raises serious concerns. While discussions about constitutional amendments are ongoing, branding Adivasi as an anti-constitutional term directly contradicts the pledge to build an inclusive Bangladesh. Such rhetoric also undermines the principles of the non-discrimination movement of the July uprising. It is crucial to ask: whose interests are being served by keeping alive the controversy left behind by the Awami regime in a Bangladesh striving for equality?

Many believe that the country is currently undergoing a process of state reform—a development we welcome. However, any progress that excludes Indigenous communities will never be truly sustainable. Beyond state reform, a transformation of the collective human mindset is essential. Only then can genuine and lasting reform take place.

Therefore, it is deeply regrettable that development in the hills is often reduced to building luxury resorts in Sajek or constructing picturesque border roads that resemble scenes from a Hollywood film. True development cannot be measured by aesthetics alone. The involvement of local communities is essential at every stage of development, and their voices must be heard in the planning process to ensure that progress is meaningful, inclusive, and sustainable.

I would like to conclude this article by discussing the demographic statistics of the Indigenous population in Bangladesh. The latest census (2022) recorded a lower number of both hill and plainland Indigenous people compared to the previous census, leading to concerns and complaints from Indigenous communities.

Let us examine the data from the 2011 and 2022 censuses. According to the 2011 census, the Indigenous population of the CHT was 920,217, but in 2022, this number dropped to 852,540. In 2011, the plainland Adivasi population was 1,586,141, accounting for 1.10 percent of the total population. However, the 2022 census recorded the combined Indigenous population of the CHT and the plains as only 1.6 million, making up just 1 percent of the country's total population.

While the overall Bengali population has increased over the past decade, it is highly unusual for hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people from both the hills and plains to seemingly "disappear" from official records. This raises a critical question—was this a deliberate attempt to underreport the Indigenous population, or was there a miscalculation in the data?

This issue must be addressed with transparency. As a key government institution, the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) cannot evade responsibility for any inaccuracies in data collection and reporting. Ensuring accurate demographic representation is essential for upholding the rights and visibility of Indigenous communities in Bangladesh.

In 2010, the Small Ethnic Communities Cultural Institutions Act officially recognised only 27 ethnic nationalities. However, following an amendment, the number of recognised ethnic groups increased to 50. Paradoxically, despite this legal expansion, the latest census recorded a significant decline in the total Indigenous population. This inconsistency demands a thorough and transparent review to understand the underlying causes.

Finally, despite these challenges and systemic discrimination, the emphasis on inclusivity in the vision for a new, non-discriminatory Bangladesh is undoubtedly a positive and promising step. We remain hopeful that by learning from the mistakes of the past, the new generation will build a harmonious and just Bangladesh—a nation where no one is left behind, regardless of caste, religion, or ethnicity.

Our aspiration is for a Bangladesh where all communities are represented and where every individual can live with dignity, preserving their unique identity and culture.

The article has been translated from Bangla to English by Priyam Paul.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments