Let us not forget the urban poor

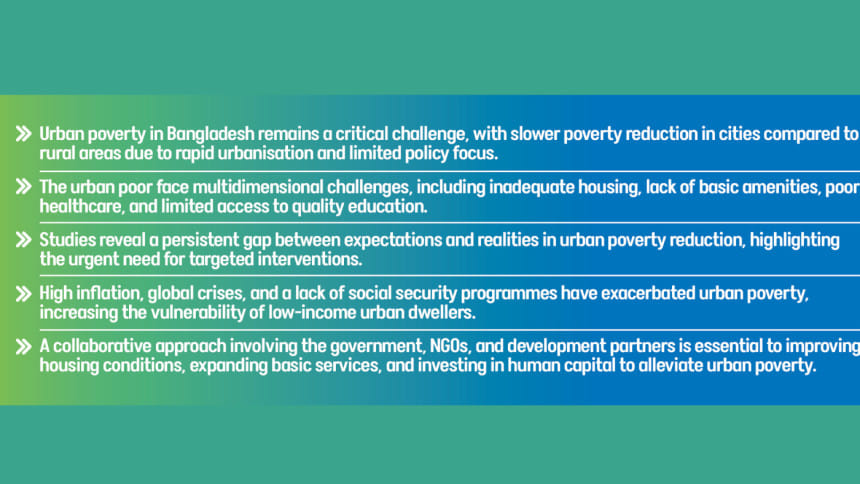

This article aims to explore the multidimensional living standards of the urban poor, identify specific reasons, and provide policy measures required to propel urban poverty alleviation in Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), in its latest report, Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2022, highlights that the headcount rate (HCR) of poverty in urban areas was 14.7 percent, while in rural areas, it was 20.5 percent, implying that poverty rates in rural areas are higher than in urban areas. However, rural areas have experienced greater reductions in poverty over time. Moreover, due to rapid urbanisation in Bangladesh, poverty reduction in urban areas has been slower.

The journey over the past two decades has not been uniform in the sense that the success in rural poverty reduction has not been mirrored in the urban context of Bangladesh, giving rise to the issue of neglect towards the urban poor and disparities in poverty reduction between urban and rural areas. A report published by the World Bank in 2019 evidenced that 90 percent of poverty reduction was rural-centric during 2010 to 2016, a period marked by the highest level of neglect towards the urban poor and marginalised communities living in urban slums. More specifically, findings on urban poverty reduction from different studies reveal that since 2010, a significant deviation between expectations and realities in urban poverty reduction has persisted, signalling a major concern for development practitioners and policymakers. More importantly, urban poverty, a complex web of challenges, encompasses not only income but also disproportionate expenses associated with housing and shelter and precarious living standards measured by a lack of food, healthcare, education, safe drinking water, proper sanitation, and security.

A deep concern in the urban setting is that we are forgetting or not taking care of children living in disadvantaged settings (e.g., slums). For example, children in urban slums more frequently suffer from acute malnutrition and stunting. The World's Mothers report, published in 2015, states that the prevalence of stunting among children living in slums (50 percent) is much higher compared to children living in non-slum urban areas (33 percent), establishing the reciprocal and intensified relationship between ill health and urban poverty, with children in slum areas bearing a disproportionately heavy burden.

Historical comparisons of multidimensional living standards between urban and rural areas would help explore how urban areas are neglected in different dimensions. The Government's Economic Review 2020 highlights the importance of urban poverty reduction, aiming to reduce the incidence of urban poverty to a commendable 10 percent by 2025. However, this ambitious goal still seems blurred due to Covid, the Russia-Ukraine war, the Middle East crisis, and political instability in the country, all of which result in higher inflation and lower purchasing power for the urban poor. Historically, greater poverty reduction in rural areas implies that development interventions in Bangladesh have been rural-focused, with limited attention given to urban poverty within national poverty reduction strategies.

Housing quality is considered one of the key dimensions of measuring poverty. A very recent study conducted by BRAC, based on Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2016), shows that despite the existence of proximity to economic opportunities between the rural and urban poor, urban poor individuals most often live in subpar housing conditions. Most importantly, this study confirms a recent decline in housing quality for urban poor households, implying neglect in terms of access to better housing. Therefore, it is crucial to address this issue through collaborative actions. Such collaborations, consisting of governmental bodies, development partners, and NGOs, might help improve housing conditions in urban areas, especially in newly urbanised areas resulting from the expansion of urban areas over time. Decent housing units need to be constructed within affordability, and it is important to introduce small and even subsidised loans to uplift housing standards, improve quality of life, and enhance overall living standards.

Neglect towards the urban poor is also reflected in the lack of access to basic amenities, including but not limited to safe and clean drinking water, electricity, and sanitation. We are all aware that guaranteed access to these amenities plays a key role in enhancing living standards, and deprivation in this regard leads to poor living conditions. Findings of the BRAC study reveal that although there has been an improvement in access to these amenities, the rate of progress is slower among the urban poor compared to their rural counterparts, implying greater neglect and deprivation of the urban poor. Therefore, it is important to bridge this gap by designing urban development projects that focus on urban poor households, especially infrastructure development in slum areas. Additionally, the government can take initiatives to ensure access to such basic amenities through subsidised tariffs and minimal connection fees. Moreover, NGOs and development organisations can initiate awareness campaigns to educate the urban poor living in low-income urban settings. All these efforts by the government, NGOs, and development partners could help upgrade the overall health and well-being of the neglected urban poor.

Education, as captured by the Human Capital Index (HCI), has a long-lasting and sustainable impact on poverty reduction. While Bangladesh has achieved tremendous success in literacy, challenges remain, especially among individuals living in poor urban households. It is estimated that around 40 percent of individuals in poor urban households still remain illiterate, highlighting the need for pro-education social safety net programmes for the urban poor. More importantly, special attention is also required for female-headed households to address gender-based disparities in adult literacy.

Due to high inflation over the last few years, urban poverty has soared as the cost of living for the urban poor has risen disproportionately. A concerning estimate of urban poverty is evident in a study jointly conducted by the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM) and the Global Development Institute (GDI) at the University of Manchester. It reports an urban poverty rate of 18.7 percent in 2023, up from 16.3 percent in 2018. However, the same study found that the rural poverty rate declined to 21.6 percent in 2023 from 24.5 percent in 2018, with a similar trend observed in rural multidimensional poverty rates, whereas urban poverty followed the opposite trajectory. Factors contributing to the rise in urban poverty since 2018 include the widespread presence of vulnerable populations, rising prices, a shortage of social security programmes in cities and towns, the Covid pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the global energy crisis.

It is of high importance to call for a concerted effort from the government, NGOs, and development partners to improve housing conditions, enhance access to essential amenities, and invest in human capital for the urban poor. If the multidimensional poverty aspects of the urban poor are effectively addressed, Bangladesh can create a more equitable and prosperous urban landscape, alleviate urban poverty, and improve the well-being of urban slum dwellers.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments