Revive our rivers by securing flow and stopping pollution

What persistent challenges in Bangladesh's river and water resource management demand immediate reform?

Water issues in Bangladesh fall into two categories: domestic and transboundary. The country faces two major transboundary disputes concerning the Teesta and Ganges rivers.

The Teesta River basin in Bangladesh covers approximately 20,000-25,000 square kilometres. However, past water experts, both international and internationally funded, have inaccurately defined the basin as only 3,000 square kilometres, confined within embankments. In reality, the Teesta extends into a larger floodplain with underground water flow connecting the Atrai and Bangali rivers to the Brahmaputra.

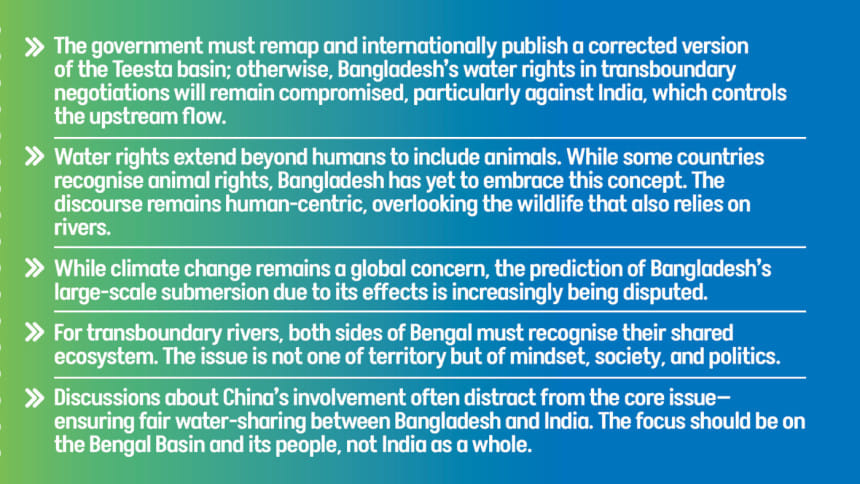

Recent estimates suggest that 20-30 million people depend on this basin. Yet, international records, particularly IUCN maps, continue to cite only 3,000 square kilometres, significantly underrepresenting the population reliant on its water. The government must remap and publish a corrected version of the Teesta basin internationally; otherwise, Bangladesh's water entitlements in transboundary negotiations will remain weakened, especially against India, which controls the upstream flow.

In transboundary water-sharing agreements, such as those under the International Watercourses Convention, basin size and dependency determine water rights. Misrepresentation of Bangladesh's basin area undermines its claim to an equitable share of Teesta's water.

A similar challenge exists with the Ganges. The focus should not be solely on the water reaching the Farakka or Gazaldoba barrages. Instead, a fixed proportional sharing system—where Bangladesh receives 70 percent and India 30 percent—should be established. During water shortages, both nations would receive less but in fair proportions. This approach fosters cooperation among dependent communities across borders. If water is blocked upstream, affected communities from both sides can jointly demand its release, promoting shared responsibility over conflict.

The Farakka Barrage has a maximum diversion capacity of 40,000 cusecs, while the Gazaldoba Barrage is limited to 10,000 cusecs. No matter how much water flows upstream, India cannot divert more than these limits. If inflows decrease, both upstream and downstream communities must collaborate on sustainable solutions.

Another emerging concern is the Brahmaputra, where China and India are constructing multiple dams in Arunachal Pradesh and upstream regions. However, these projects are expected to have minimal impact on Bangladesh's water availability. Similarly, the once-contentious Tipaimukh Dam in the Meghna basin is no longer a major concern since its construction was abandoned.

At the domestic level, every river—whether originating from a small stream (chara) or marshland—must maintain a minimum flow. Many Bangladeshi rivers originate from marshlands, and preserving their natural flow is crucial.

During winter, rivers naturally experience low flow, yet historically, water has always been present. This historical right to water must not be obstructed. In my 2008 book, I argued that water rights extend beyond humans to animals. While some countries recognise animal rights, Bangladesh has yet to acknowledge this concept. The discourse remains human-centric, ignoring the wildlife that also depends on rivers.

For thousands of years, humans and animals coexisted with natural water cycles. While floods and droughts occur, both have adapted to these fluctuations. However, artificially halting river flows disrupts ecosystems, driving species toward extinction.

Protecting domestic rivers is essential. The minimum flow of any river—whether the Teesta, Buriganga, or any other—must be preserved. Excess water from rainfall or floods should flow downstream naturally, but minimum flows must never be blocked.

Additionally, river pollution must be strictly controlled. Industrial waste is the greatest threat. Unlike organic waste, which aquatic organisms can break down, chemical pollutants from factories are toxic and irreversible.

Thus, I strongly advocate for two fundamental principles in domestic water management: ensuring a continuous minimum flow in all rivers and preventing industrial pollution.

How do you assess the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100, which aims to secure the future of water resources while mitigating climate change and natural disasters?

The Delta Plan addresses two key concerns: managing water resources and mitigating climate change. Regarding climate change, it has been claimed that one-third of Bangladesh's delta will submerge. I have consistently disagreed with this claim. Why? Because around 1,400 million tons of silt flow downstream each year, extending Bangladesh's landmass by roughly 300 square kilometres annually.

This natural process has been ongoing for millennia. The Bengal region has gradually risen from the sea due to silt deposition. In Dhaka, sedimentary rock layers extend five kilometres deep, while in Kuakata, they reach about 20 kilometres. Moreover, Bangladesh's continental shelf extends 200 nautical miles southward into the sea, also accumulating silt.

Thus, climate change has a minimal impact in this regard. While climate change is a global concern, the theory predicting Bangladesh's large-scale submersion is increasingly questioned. Global discussions are now reconsidering earlier projections.

The second major issue is water resource management. The Delta Plan emphasises embankments and infrastructure projects, but it cannot generate additional water—it can only manage what naturally exists, whether from rainfall or upstream sources.

As a lower riparian country, how can Bangladesh effectively address transboundary river water-sharing issues with India?

Since independence, Bangladesh and India have had a Joint River Commission with experts from both sides. However, over the past 54 years, our representatives have often attended meetings unprepared. Indian delegates present well-researched proposals, while our officials tend to agree without thorough analysis.

When the Teesta water-sharing agreement was discussed, I was among the first to highlight concerns. I published an article with satellite images of the Gazaldoba Barrage, showing how water was being diverted. In 2012, satellite imagery confirmed this diversion, yet I doubt our negotiators fully understood its implications.

Bengal is a shared geographical and cultural space, historically a single entity divided politically into West Bengal and Bangladesh. Despite this division, we share rivers, floodplains, and livelihoods. Official negotiations must be backed by rigorous research, facts, and strategic planning.

The Teesta agreement failed because Mamata Banerjee opposed it, citing water shortages. However, no one questioned where the water had gone. If Bangladesh had not received it and West Bengal also claimed scarcity, then where was it? The answer lies in Sikkim, where multiple dams hold up the water. These dams should follow a "run-of-the-river" principle, ensuring natural minimum flow while storing excess rainwater. Instead, they are blocking even the lowest flow, causing severe shortages downstream.

Bangladesh could have proposed to Mamata Banerjee that both sides jointly pressure Sikkim to ensure compliance with dam operation rules. Instead of treating this as a Bangladesh-West Bengal conflict, it should have been framed as a shared issue affecting both regions. The deprivation is mutual, and cooperation—not confrontation—is key.

For transboundary rivers, both sides of Bengal must acknowledge their shared ecosystem. The problem is not territorial but psychological, social, and political. Some believe resolving land disputes, such as Tin Bigha or the Chicken's Neck corridor, is the solution, but the real issue is effective water management.

What is the best way to resolve the Teesta Barrage issue amid India-China interests and India's pending water-sharing deal with Bangladesh?

As I've emphasised, thorough research must precede negotiations, and a collaborative approach should be adopted. This is a shared problem that requires cooperation, not division.

China is not directly involved in the Teesta issue. While it could play a role in navigational projects, beyond Assam, no viable navigational route exists. The waterway extends only up to Sadiya in the Dibrugarh region, remaining within Assam, with further connectivity leading to the Bay of Bengal.

China has undertaken major water-related projects, but these do not directly threaten Bangladesh. Earlier, there was speculation that China would divert Brahmaputra water to its mainland, but this is economically and technically unfeasible due to mountain ridges separating Tibet from China's heartland.

China's hydroelectric projects are tunnel-based and primarily serve its energy needs. They do not divert water at a scale detrimental to Bangladesh. Discussions about China's involvement often distract from the core issue—ensuring fair water-sharing between Bangladesh and India. The focus should be on the Bengal Basin and its people, not India as a whole.

Currently, when water shortages arise, one side suffers while the other remains indifferent, each prioritising its own interests. But if both sides unite, they can approach Delhi with a single voice: "Why are you not releasing water? We are both suffering." This shared responsibility is crucial for securing fair water distribution.

This is why I reject superficial cooperation without a foundation of unity. True cooperation must be built on a sense of shared purpose and fairness. Only then can we achieve meaningful, long-term solutions.

The government plans to restore 19 channels and a 125-kilometre river network. However, similar commitments in the past have failed. What are your recommendations for ensuring effective implementation this time?

While excavation projects are undertaken, a critical issue is the disposal of excavated material. Typically, soil and waste are dumped along the banks, only to erode back into the water within a year or two, rendering the effort futile.

In Dhaka, the problem is compounded by excessive garbage accumulation, particularly in areas like Keraniganj, Gazipur, and Narayanganj. A more effective approach would be to incinerate extracted waste immediately, especially in winter when conditions are favourable. This would not only eliminate waste but also produce ash, which could be used as fertiliser.

Despite the potential, such methods are ignored. For two decades, Dhaka City Corporation has discussed generating electricity from waste but has failed to act. Cities like Bangalore complete metro rail projects in under three years, while in Bangladesh, even basic infrastructure takes decades. Dhaka produces 5,000-6,000 tons of solid waste annually, which could power waste-to-energy plants generating at least 10 megawatts each. Without such solutions, dredged waste will inevitably return, repeating the failures of past decades.

How can the National River Conservation Commission (NRCC) effectively tackle river encroachment?

The NRCC should be independent and answerable to parliament rather than controlled by a ministry. Ideally, all commissions should fall under an ombudsman, ensuring impartial oversight. Currently, the NRCC operates under the Shipping Ministry, which has limited jurisdiction. For true effectiveness, it must be free from political influence and act in the nation's best interest.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments