The impact of development on our hills and forests

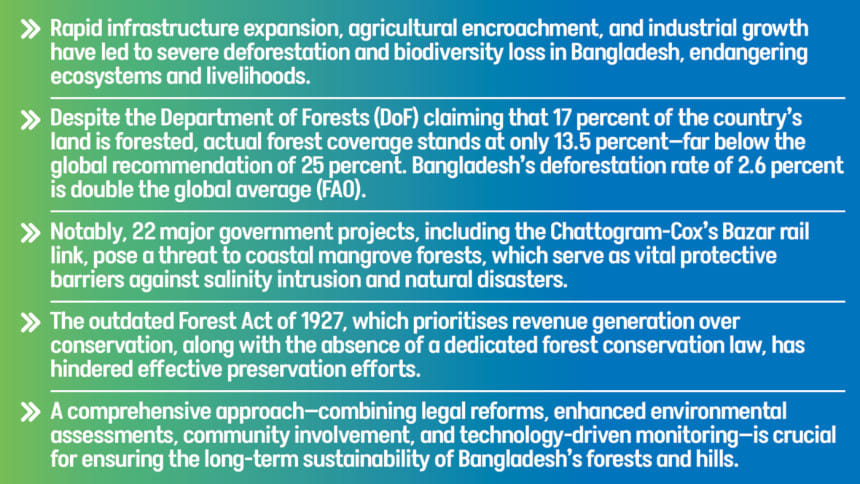

Bangladesh, a country with a rich natural heritage, faces significant challenges in balancing development with environmental sustainability. The country's development agenda has been anthropocentric, short-sighted, unregulated, and top-down, lacking public consultation and concern for ecological consequences. This has resulted in the severe degradation of nearly all its ecosystems and natural resources. Its forests and hills, vital to biodiversity, climate regulation, and the livelihoods of millions, are under immense pressure from rapid development. This pressure comes in the form of infrastructure expansion, agricultural encroachment, urbanisation, and industrial growth. The impact of these developments on Bangladesh's forests and hills has been profound, leading to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation. Addressing this complex issue requires a concerted effort, including legal reforms, stricter enforcement of existing laws, and a more sustainable approach to development.

THE STATE OF FORESTS AND HILLS IN BANGLADESH

Bangladesh's forests are primarily concentrated in the southeastern and northeastern regions, with the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) serving as the country's ecological heart. These forests play a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance, preventing soil erosion, protecting water sources, and providing habitats for diverse flora and fauna. The hills, particularly in the CHT, are not only home to unique biodiversity but also to indigenous communities whose livelihoods depend on sustainable resource use.

Unchecked development has severely impacted forested areas, with forests frequently sacrificed for large-scale projects. Despite the Department of Forests (DoF) claiming that 17 percent of the country's land is forested, actual forest coverage stands at only 13.5 percent—far below the global recommendation of 25 percent. Bangladesh's deforestation rate of 2.6 percent is double the global average (FAO). In 2023 alone, the country lost 20.2 kilo-hectares (kha) of natural forest, releasing 11.6 million tonnes (Mt) of CO₂ emissions. Between 2002 and 2023, Bangladesh lost 8.39 kha of humid primary forest, accounting for 3.5 percent of its total tree cover loss (Global Forest Watch). Over the past 17 years, 66 square kilometres of tropical rainforest have been destroyed. Additionally, 287,453 acres of forest land have been occupied, including 138,000 acres of reserved forest (DoF).

DEVELOPMENT AND ITS IMPACT ON FORESTS AND HILLS

Forest land in Bangladesh is increasingly encroached upon in the name of development, despite a court ban on such conversions. The government aims to increase forest coverage to 20 percent, yet deforestation continues, particularly due to government projects. In 2019 alone, 160,000 acres of forest were allocated to various government agencies or used for development projects.

Notably, 22 major government projects, including the Chattogram-Cox's Bazar rail link, threaten coastal mangrove forests, which are crucial protective barriers against salinity intrusion and natural disasters. This railway project, spanning 101 km, cuts through Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary, Fasiakhali Wildlife Sanctuary, and Medhkachapia National Park, endangering species such as the Asian elephant.

In 2024, an elephant was killed by a train in Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary. The project has already led to the destruction of 720,000 trees and parts of 26 hills.

Other harmful developments include the construction of an oil terminal on 191.25 acres of reserved forest land in Moheshkhali (2017–18) and a proposed civil service training academy on 700 acres of protected forest and ecologically critical land—cancelled only after a legal challenge. While some harmful projects, such as the Safari Park in Lathitila's reserved forest in Moulvibazar and the Bangladesh Football Federation's residential training facility in Cox's Bazar (which involved de-reserving 20 acres in 2022), have been halted, ongoing legal measures remain essential to prevent further degradation.

LEGAL ASPECTS OF FOREST AND HILL CONSERVATION IN BANGLADESH

To stem the tide of deforestation, adequate administrative and legal frameworks are essential. However, at present, Bangladesh has neither. The Forest Act of 1927, a colonial-era law, governs public forests in Bangladesh. It primarily views forests as a source of revenue, focusing on regulating timber transit and imposing duties. Unlike India, Bangladesh has not enacted a specific law for forest conservation, and the 1927 Act has remained in place despite amendments introducing provisions for social forestry and increasing penalties for certain offences. Under the Forest Act, the government has the authority to take control of any forest land over which it holds proprietary rights, managing it as either "reserved" or "protected" forest. In practice, a significant portion of natural forests has been designated as "reserved forest," but final notifications to officially declare these areas remain pending. Delays in finalising these declarations are primarily due to unresolved issues regarding the rights of forest-dwelling communities, such as land use, access to pasture, forest products, right of way, and water resources, as outlined in Sections 11 and 12 of the Act.

Bangladesh has yet to pass a law that officially recognises the forest rights of ethnic minorities. The matter has been addressed by the High Court, which directed the government to form a committee to address the rights of the Garo ethnic communities in the Madhupur Sal Forest, covering 44,000 acres and impacting 8,630 families. While the Forest Act promotes community forestry through village forestry (Section 28), management remains largely under government control. Additionally, social forestry was introduced through an amendment to the Act in 2000. However, social forestry remains under government control, particularly that of the Forest Department, with the goal of cultivating trees for timber production, benefiting local communities through the sale of wood. Social forestry in no way supports the conservation of natural forests. Ongoing issues such as encroachments and unclear land boundaries further hinder effective forest conservation, with the government failing to resolve disputes and manage forest resources efficiently. Furthermore, the Forest Act lacks provisions for ecosystem-based forest management, which is crucial for long-term conservation.

The proposed Forest Conservation Bill of 2023, set to replace the outdated Forest Act, will empower forest officials to protect forests and biodiversity. It aims to end the revenue-driven approach of auctioning timber and issuing permits for extracting resources from forests, including the Sundarbans, a critical sanctuary for the endangered Bengal tiger. The Bill also prohibits tree cutting outside forests, significantly impacting the environment. However, it remains in draft form. Moreover, the Environment Conservation Act of 1995 (amended in 2010), a significant piece of legislation aimed at preventing environmental degradation in Bangladesh, grants the Department of Environment (DoE) the authority to oversee projects that may harm the environment, including development projects in forested and hilly regions. However, its implementation has been inconsistent, with many large projects approved without proper environmental assessments, leading to irreversible damage to ecosystems.

AN AGENDA FOR THE FUTURE: INTEGRATING SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

To address the mounting environmental challenges facing Bangladesh's forests and hills, a multi-pronged approach is needed. The government must update and strengthen environmental laws to prevent land conversion and illegal deforestation, with improved coordination among the Forest Department, the Department of Environment, and local governments. Future developments should prioritise sustainability through environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and the regeneration of natural forests to curb deforestation. Protecting indigenous land rights and involving local communities in decision-making is crucial. Finally, leveraging technology such as satellite imagery and GIS for monitoring, along with enhancing transparency and public participation, can help enforce laws and reduce illegal activities.

CONCLUSION

The forests and hills of Bangladesh are at a critical juncture. The country's rapid development has placed immense pressure on its natural resources, leading to significant environmental degradation. However, through a comprehensive agenda that includes legal reforms, enhanced enforcement, and sustainable development practices, Bangladesh can chart a path towards a more environmentally secure future. Protecting these vital ecosystems will not only preserve biodiversity and safeguard the livelihoods of indigenous communities but will also ensure the country's resilience in the face of climate change. The future of Bangladesh's forests and hills rests on the choices made today—an agenda for the future that must prioritise both development and conservation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments