The need for power sector reforms

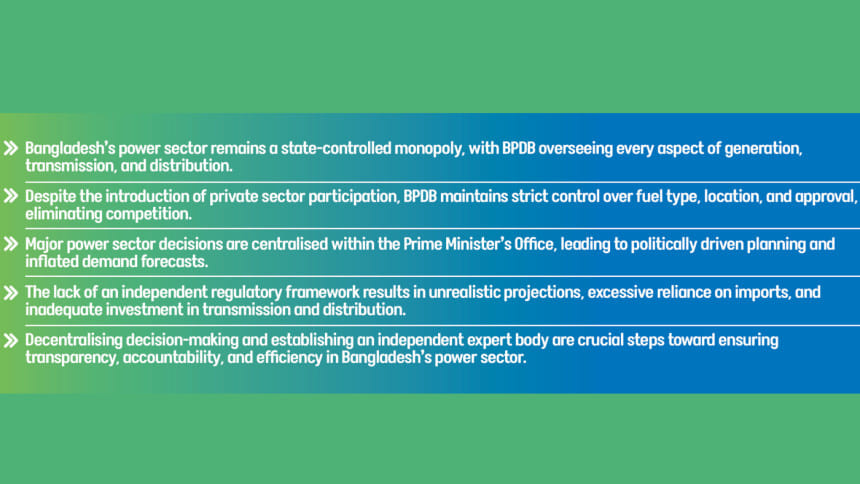

In a way, Bangladesh maintains a vertically integrated state monopoly in the power sector. Although the generation segment was liberalised by the private sector power generation policy of 1996, the growth of private generation is fully controlled by the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) in terms of fuel type, location, size, and approval. There is no competition, as BPDB is the single buyer. Similarly, generation was segregated, and the distribution system was divided among government-formed distribution companies (DisCos) without any true freedom except self-governance within the franchise. BPDB is the single seller of electricity to the transmission company Power Grid Bangladesh (PGCB), which allocates power to the DisCos through the National Load Dispatch Centre (NLDC), which it controls.

Essentially, BPDB controls every aspect of the entire power sector. In addition, BPDB is entrusted with forecasting demand along with a supply plan. Even with so much power and apparent control, BPDB cannot function independently because it is an agency under the Ministry of Power, Energy, and Mineral Resources. This ministry, for most of the last three decades, has been headed by the prime minister for "strategic national security." Almost all major power sector decisions were influenced and eventually decided by the Prime Minister's Office (PMO). The political economy of the power sector involved the PMO, the ministry, BPDB, and opportunist businesses. In the guise of political ambition, the power sector's national strategy was increasingly influenced by financial and political transactions. The Power System Master Plan (PSMP) 2016 was revisited by BPDB, as directed by the ministry, to inflate the demand forecast that was used to award a number of power plants through the Quick Enhancement of Electricity and Energy Supply (Special Provisions) Act, 2010, with impunity.

The Bangladesh power sector is structured in such a way that it is easy to control from a single point (PMO). Curtailing the power of Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission (BERC) made it even easier for the political masters to manipulate producers' and consumers' tariffs, silencing every voice of reason. In all advanced countries, transmission and distribution companies control the power sector under a regulatory framework without government interference. There are multiple suppliers (generation) and multiple buyers (transmission companies, DisCos, retailers) in the wholesale market, from long-term to next-day hourly trading. Any DisCo, retailer, or even consumer can have a bilateral long-term contract with a generation company of their choice. Even in areas where this full free-market model is not in place, the regulator—not the government—determines the mode of operation.

Bangladesh is perhaps not fully ready to move to a wholesale market model yet, principally due to poor infrastructure and a lack of smart systems, but the single-point control must be broken. If the decision-making process is decentralised, the nexus of politicians, bureaucrats, and businesses will be dismantled. The influence of the ministry in the power sector should be minimal. The first tool of power sector development is the demand forecast. So far, four long-term forecasts have been formulated: PSMP 2005, 2010, 2016, and Integrated Energy and Power Master Plan (IEPMP) 2023.

Except for the first one, all three were conducted by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) based on data fed by BPDB, various government plans, objectives, and policies. No independent study or verification of data was conducted, especially regarding the economic goals set by the government. While only a couple of special economic zones have barely started their journey, the planning included the lofty demand for 100 such projects. The Perspective Plan 2041 assumes an unrealistic 9 percent GDP growth for almost 20 years, yet that was the plan fed to the IEPMP 2023 team. All these plans are meant for 20-year projections, allowing the ruling party to politicise the numbers. In a fast-moving international energy scenario, none of the plans indicated a clear transition path for the country toward a clean energy option. JICA has been accused of promoting Japanese technology that is not suitable for Bangladesh.

Bangladesh needs a team of experts who understand the local perspective and are free from political influence to calculate electricity demand. Each of the previous plans focused only on demand and generation, with no mention of sourcing primary energy, relying heavily on imports. Similarly, investment requirements in transmission and distribution were overlooked. The demand forecast was based on ambitious policy-driven sector growth and unrealistic GDP growth predictions.

Bangladesh needs a five-year moving plan to meet its power demand based on Integrated Resource Planning, where sector-wise demand forecasts from real field data would be predicted. Before deciding on large power plants, regional demand mapping and possible distributed systems focusing on local solutions should be explored. The role and extent of renewable energy should also be considered. This plan should conduct a detailed financial analysis of the system, including primary energy, national infrastructure, import facilities, risk assessment, etc. An additional five-year extrapolation can be incorporated into the planning. This five-plus-five-year plan should be reviewed and updated annually to avoid over- or underestimating demand.

Until a market-based system is developed, an independent body should be formed, comprising academics, professionals, and regulators, to make every power sector decision involving generation, transmission, and distribution. The implementing agencies should only follow the directives of this body. The collective decision of such a body would ensure that it is not influenced by politicians, businesses, bureaucrats, or any other interest groups. Forming such a powerful body will be challenging, but under the current framework, it is the only way to avoid single-point control and ensure accountability and transparency.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments