In the shadow of a larger-than-life father

Sheikh Hasina, Leader of the Opposition in parliament and president of the Bangladesh Awami League, is more than a daughter of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. She is the inheritor of Mujib's political legacy, the torch-bearer of his ideals. On the occasion of Bangabandhu's 17th death anniversary, Hasina talked to The Daily Star frankly about her childhood, about the way she learnt her politics and the lasting influence that her father, and crucially, her mother (the late Begum Fazilatunnesa) left on her. It was a relaxed and candid Sheikh Hasina who spoke to the Star team led by Editor SM Ali.

Daily Star (DS): You may not have any memories of Sheikh Shaheb of the early years, like his role in the menial workers strike of 1949. But what are your earliest memories?

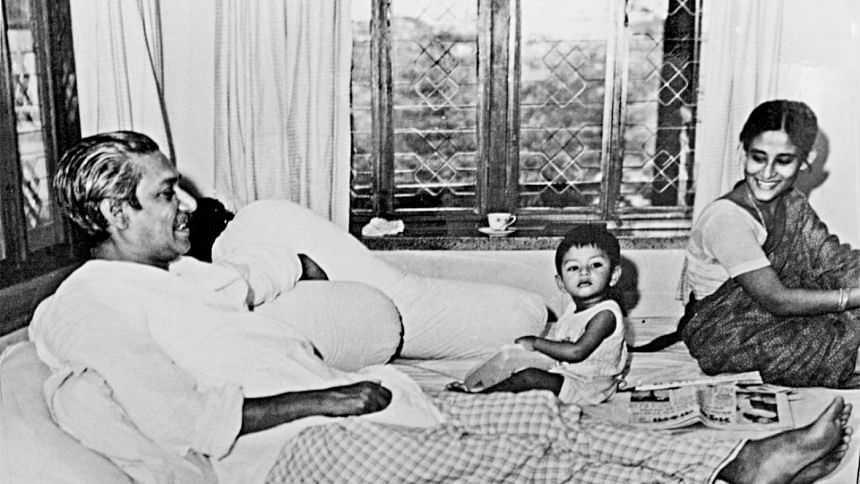

Sheikh Hasina (SH): When we were little in our village, we didn't have the opportunity to be with our father. He was in jail from 1949 to 1952.

When he used to come to Gopalganj to attend court, we used to see him then. My younger brother Kamal hardly even knew our father, because he was born after me and didn't get to see him.

One of my earliest memories of Gopalganj is the time Kamal asked me, “Can I also call your dad, dad?” So, I told father about that.

When in 1952 father went on hunger strike in jail, our grandfather took us to Dhaka by boat, where we stayed with some relations. Towards the end of February (on the 28th) father was released from jail. His condition was really bad then and he was very sick due to the hunger strike. Grandfather then took him to Tongipara. Doctors' advice then was complete bedrest.

It was then that we were with father for some time and he used to take us to bathe in the pond or take us along with him when he used to go to the town.

Then he went back to Dhaka and during the election campaign of 1954 we used to run around. Lots of us kids in the village used to run around for the United Front campaign. When the older ones used to go on canvassing in the villages, we used to run after them.

DS: Now a lot of people think that those who engaged in politics become detached from their families. How was it with your father? Did you have him near you, or was he always away from home?

SH: Let me narrate a story here. It was around 1957 and we were living in Dhaka. But every holiday we used to invariably spend some time in our village home, because going back to the village was like an addiction for us.

During one such visit, some of us youngsters were playing and bathing in the pond. Then a girl who was a relation, asked her father to fasten the belt of her frock tightly.

I noticed that she was addressing her father as 'tumi'. So I asked her, “Do you address your dad as tumi?” She then asked me, “What do you call your dad?”

Suddenly I realised that I didn't know! Because I'd hardly had the chance to call my father abba.

We used to go to morning school and when we'd leave the house, father would be asleep. We used to get back around midday, by then father would be in the office. And when he would return in the afternoon, we'd be out playing.

As a result, we hardly used to meet one another. And I didn't know what I called him! Later that girl's father told my father that, because of his politics his own daughter didn't know what to call him.

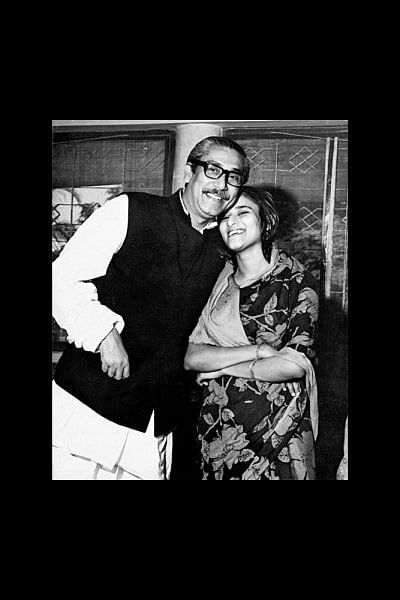

Then our father got hold of us, sat us down and said, “Ok, what do you want to call me? Call me abba, call me abba as many times as you want, call me abba to your heart's content!”

After that, he always used to get back home little earlier, sit with us for lunch and always mixed rice and yogurt or milk with his own hands and put it up to our mouth. Then when he would get back at night, he would always ask if we had eaten. If we hadn't, then he would wake us up and feed us.

From then on, he always took extra care in enquiring about what we were doing and how we were. I have to confess that I built up a bad habit. Not only when I was in school, but even after I was married and had children. I didn't use to eat at night. Whenever I used to stay with my father, I used to wait because I knew he would get us out of bed and eat with us. It was as if that, whether I ate or not was more of his concern than mine.

So, that one incident about me not knowing what to call him, made him come close to us for always. Even though father used to be in jail quite often and for long stretches, whenever we had him near us, we had so much of him and he was so caring that we never felt any want.

Amid all his monumental work, he still found time to check if we had eaten, if we had put up the mosquito net on our bed or even if I had tied my hair before going to bed.

DS: You had all the attention and love from your father, but where did his politics fit in? When or how did you become aware that your father was doing this and this, and that there was a positive politics behind it?

SH: As you know, the one and only focus of father's politics was the poor people of this country. He used to love the people. Even at home, there were always people coming for help and I never saw my father shy away from helping people in whatever way he could. He always felt that the people of his country were very poor and that he had to do something for them.

Even if we did not understand the details of his politics, we always knew that he loved the people and he had a special feeling for, and sense of responsibility towards his country. That much we understood from an early age.

For instance, after the United Front Ministry was elected in 1954, and we were living in No 3 Minto Road, one day, my mother told us that father had been arrested the night before. Then we used to visit him in jail and we always realised that he was put in jail so often because he loved the people.

I remember that when police came to arrest father after martial law was declared in 1958, they searched our house thoroughly. They seized everything they found there. The real tragedy for me was that they ransacked all my playthings, especially all the dolls and their little houses and beds. They threw everything around and that was really painful for me.

I remember my grandmother was crying as the police took my father away. I was crying too. But before the police jeep moved out, father waved at us. Then we were moved out of the house and our mother was virtually on the street with us four young ones, but we managed to move into a rented house.

So, you can say I have learnt my politics from life itself. We went through so much sufferings and pain, but we never complained to our father. And my mother had a lot to do with that. You can say that it was from our mother that we learnt to sacrifice and endure. Because, if mother had complained, and if she had expressed any grievance or unhappiness, then we would have grown up with a different attitude.

My mother had always accepted that father would devote himself to politics because he loved the people and wanted to work for the wellbeing of the country.

I was in class seven when I went to Azimpur Girls School, and while there I always went to meetings and processions. But when I went to Eden College after getting my matric in 1965, then I became more active. At that time, Chhatra Union of Matia (Chowdhury) apa was very strong and our Chhatra League was not in a favourable position at Eden College.

But in 1966-67, I was under pressure from my friends to contest the college students union elections because they thought I'd win and that would be a big boost for the party.

On the other hand, many people thought we would lose because Matia apa was so strong and people including Moni bhai (Sheikh Fazlul Huq) who was in jail, sent messages asking me not to stand. They thought that if I lost, then that would reflect badly on the Six Point Programme which had just been launched by father. In the end I did contest the election and won.

DS: You've said that you learnt politics from life itself. But was there ever a moment when Bangabandhu tried, consciously, to educate or enlighten you about his politics?

SH: Actually, the atmosphere in our house wasn't such that father would sit us down and say, “Let's learn politics.”

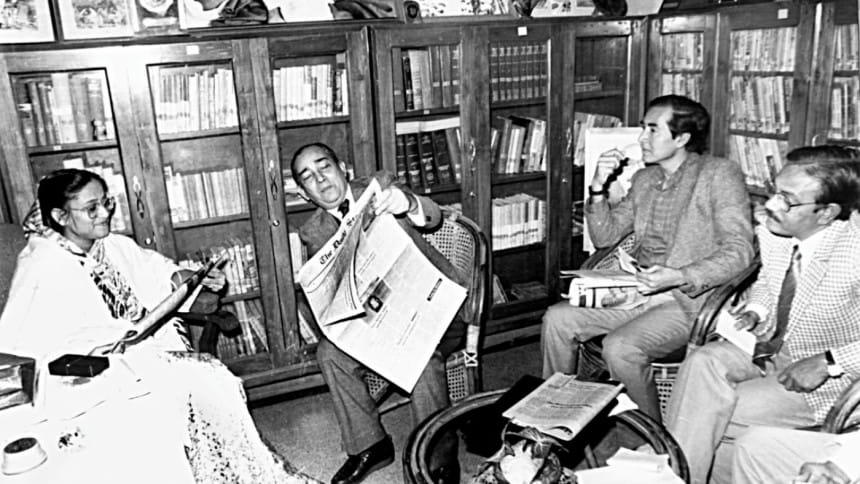

There was no opportunity for that and indeed there was no need for that. It was a natural process. The whole atmosphere was a political one. We used to discuss everything with father, whether politics or anything else.

And we had the habit of reading newspapers. When father used to be out of prison, we used to all sit together and read the papers. Then we used to discuss things from the papers, whether politics, or sports or anything.

DS: Did Sheikh Shaheb discuss matters of principle such as nationalism, secularism, socialism and democracy? Did he used to discuss things related to the four points?

SH: Yes, all the time. Let me tell you a little a story.

We had a subject at school called Social Knowledge, and there was a chapter on Pakistan in the book. It was Ayub Khan's time and the chapter had profuse praises for Ayub.

So I showed it to my father and said, look what they've written. My father told me to forget it. He said, “All these Pakistan business won't last, you don't have to waste your time reading about it.”

I had written down everything father said about Ayub and military dictators on the back of the book. Then, during the school exams, I wrote those things down in answer to a question about Ayub and Pakistan.

Now, the teacher was a CSP officer's wife and she was so annoyed that she failed me for that whole subject!

Later, my private tutor went and checked my exam paper which he always did. He found that the teacher had written next to my answer, “This girl doesn't read any book, she obviously goes around listening to political speeches only.”

Later during my matric, I took the Social Knowledge exam without answering questions on the Pakistan chapter. That meant sacrificing 20 marks which was really risky because I could have failed. But it was like a principle, I refused to read anything about Pakistan on the textbooks.

We used to discuss all sorts of matters with father. He always spoke openly and seriously with us, he never treated us like kids or as someone who were too young to understand political things.

And whenever we had questions, we always went straight to him and asked. I had a bad habit in that I was very argumentative. I don't know why but I always used to argue with father. Whatever the topic, I used to contradict and argue with him. Mother used to get quite annoyed sometimes.

DS: Did all of your brothers and sisters have this habit?

SH: More or less, but Kamal was less so. There was a little gap between him and father from his childhood, as I said earlier, and it wasn't totally filled. So he was a little shy with father.

But I was too argumentative, and so was Rehana, my younger sister. That's why if I had any political questions I never used to hesitate to ask.

Whenever father was out of jail, our morning used to start with him, a cup of tea and the newspapers.

DS: You used to visit Bangabandhu in prison, of course. In what sort of a mood did you used to find him?

SH: We learnt one thing from our father, and that was to accept with a smile any kind of pain or sufferings. Father never used to sit in gloom if there was any danger or hardship. He always used to make light of any danger and laugh with it. It was a family trait.

My mother played a vital role. She was highly aware politically. During my father's absence, she had to look after Awami League as well as her family.

She used to take information to father and bring back instructions. It was a difficult job, because plainclothes policemen always used to shadow us.

Mother was supportive to the utmost. Father never had to worry about family problems, mother used to take care of everything.

DS: Did he used to talk about prison life much?

SH: Oh yes, he used to talk about the jail. Most of the times father used to be kept isolated from other prisoners.

Father used to talk about his own cooking, that is whenever he tried to cook something by himself. He used to have pet cats and birds in his separate cell. He used to talk about those.

Once a cat gave birth to some kittens and he got very worried when he saw the mother cat picking her kittens up with her teeth and take them with her here and there.

He didn't know cats do that until the eyes of the kittens are fully opened! He got worried about the kittens' eyes not opening. So he arranged for a vet to come and have a look at the kittens.

He used to really look after his cats, birds and a small garden he tended next to his cell. He always used to put out food for other wild birds and every time we visited him, he would talk about the number of birds that came to eat in his garden that day.

DS: At that time, did you ever feel that you'd have a political role in this country?

SH: Well, actually, because I was born into a political family, I never used to think quite along that line.

Nowadays, I often jokingly tell Chhatra League leaders that “I did so much work for the Chhatra League but you people never made me a member of the Central Committee!”

I joke about it now, but at that time I never thought that I'd have to have a post. I did whatever was necessary at the time, like contesting the Eden College elections. The Chhatra League felt I ought to stand for the Eden elections, so I did.

DS: Did you ever think, say in the late '50s or '60s, that Bangabandhu would one day become the leader or Prime Minister of this country?

SH: I never got any impression from him along that line. He never gave much thought to it. To him, what he would do was more important than what he would become.

DS: You became actively involved in Bangladesh politics after you came back home in 1981...

SH: Yes, but before that when I was in England, I was involved indirectly.

When Zia (Major General Ziaur Rahman) became a military dictator, became president and this or that, we used to oppose it. There was a newspaper published after 1975 from London called Banglar Dak and we used to get stories printed.

I used to be directly involved with the Bangabandhu Parishad in England in 1980. I used to attend Awami League meetings, give speeches, etc., but was not a party member and the reality is, I hadn't thought about being directly involved in party affairs. My main interest was to do research work, writings, etc., with the Bangabandhu Parishad.

I wanted to mostly do social work. My father always felt something had to be done for the people, and he was also very conscience of the sacrifices Awami League workers always made for the party.

In England, I had helped out in making AL stronger by doing organisational work. I didn't think of holding a post or taking on as big a responsibility as I have now.

DS: After the elections of 1970, we said that Sheikh Shaheb was the next prime minister of Pakistan. In your family circles, did you have any discussions like “my father is the next prime minister of Pakistan” or something like that?

SH: There was no scope for that!

Let me say this, when the Six Point Programme was presented by my father, it was more or less clear from then on that Bangladesh was going to become independent.

That is why, our thinking was not so much whether father would become prime minister of Pakistan; rather the thought was more on how Bangladesh would become independent. Within the family, it never simply occurred to us that we might have to go and live in Rawalpindi or Islamabad. My mother would never had gone over there anyway!

DS: Lot of people have commented that the house at No 32 Dhanmondi, with its low boundary wall and small area, was a big security risk. That the president's security could not be guaranteed in that house.

SH: My mother believed that my father had dedicated his own life for the welfare of the people. Father had a tremendous faith in and love for the people of this country.

He felt that if he had gone to a well-protected house, then he would become isolated from the people. And my mother felt that if the family moved to an official place, then all the pomp and surroundings would spoil the children.

We were an ordinary family, and we wanted to maintain that life. Father, despite being the prime minister and later president, continued to lead an ordinary life.

I feel now that it was not the right approach. At least, some protection should have been provided by the government or the party.

But then, whenever somebody mentioned security, my mother always said that the ordinary people of this country would never harm him. She always said that those who stood guard would be the ones to turn their guns on him.

And that was what really happened. Wherever father might have been, he was murdered by people who were very close to him. Think of Khondker Mushtaque. And Major Dalim was virtually like a member of the family, his wife and mother-in-law used to come to our house all the time.

DS: Thank you, Leader of the Opposition, for your time.

Originally published on August 15, 1992, The Daily Star.

Comments