A journey from darkness to light

On 28 December he [jail superintendent] came to me and said that I should pack up as he had received an order that I was to ‘shift to new location’. My immediate reaction was one of joy, at the prospect of leaving the jail after nearly nine months of solitary confinement. But, this was overtaken by anxiety as to what awaited me. After a few suspenseful hours, I was taken to the jail office near the jail gate. The small sum of money I had on me which I had been required to hand over to the Superintendent when I had entered was returned to me. I was also given about half a dozen books that had been sent by my family, but had never been delivered to me. I acknowledged receipt of these, along with a few of my clothes and a couple of notebooks, by signing a register. As these formalities were being completed, two tall persons in civilian clothes, but with short-cropped hair which suggested that they were military personnel, entered and asked me to accompany them towards the jail gate. As I followed them out, I was escorted to a Volkswagen car and sat in the backseat with one of the two escorts, while the other took the seat next to the driver. At a little distance, I saw a military truck with armed personnel which followed our car as it left for what was, for me, an unknown destination.

As the car entered the highway, which I recognised as the Rawalpindi-Peshawar highway, it was directed towards Rawalpindi, but, my anxiety was heightened when it by-passed it. It was now dark, and the destination was still unknown.

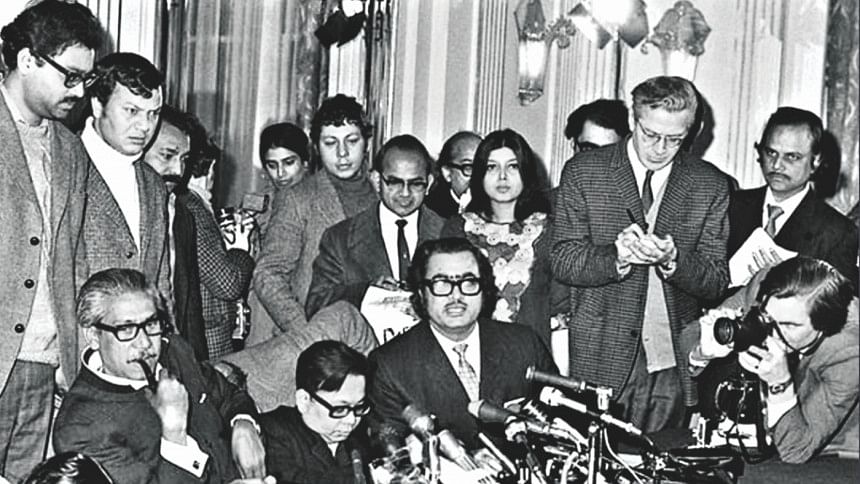

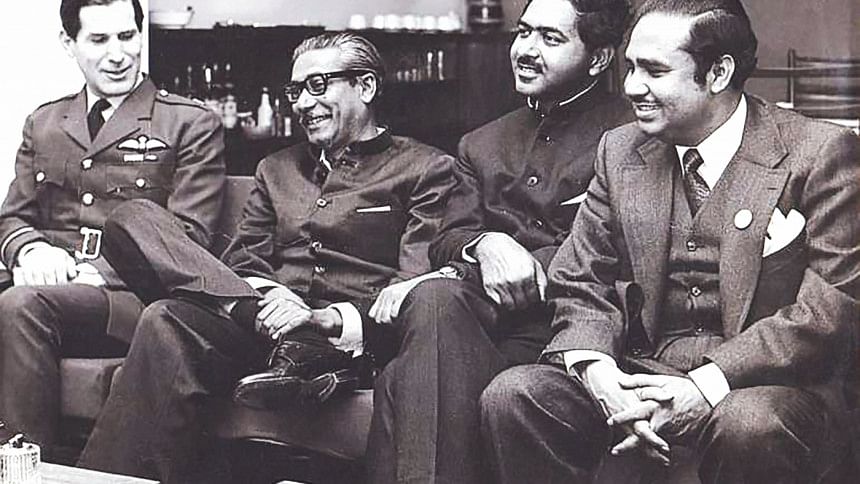

After proceeding down the highway the car sharply turned into what appeared to be an unpaved road. I turned to my escort and asked where we were going. Noting the apprehension reflected in my query, he said, ‘You would like it’. Just then, I noticed that armed personnel with pointed machine guns had surrounded the car. Sensing danger, I asked where we were precisely going. A small bungalow in the distance was pointed out and the escort said that we were going there, and again repeated, ‘You will like it’. The armed guards made way for the car and it proceeded towards the bungalow. A senior officer came out and asked me to enter the bungalow. As I entered, he pointed to a row of rooms and asked me to enter room number one. I did so and was overwhelmed by emotion when I saw Bangabandhu standing there. He embraced me and said he had been waiting all day, and asked why it had taken so long. I told him I had got myself ready in the afternoon, and it was not till evening that I was finally released. It had taken some hours to reach there. The place where we were was, I learnt, the compound of a police academy at Shihala, not far from Rawalpindi. Bangabandhu had been brought there two days earlier. He recounted that his journey from Mianwali jail started soon after 16 December; that day tension had mounted in the jail as Mianwali was the hometown of General Niazi, who had surrendered in Dhaka. The senior police official as in-charge of Bangabandhu had told him that he felt it was unsafe for Bangabandhu to remain in that jail, and that he (the police officer) proposed to take him out, on his own responsibility, under police guard to a safer place. He had then taken Bangabandhu to a location where a major project had been completed and a number of vacant bungalows were available.

After he had been there for a couple of days, a helicopter had arrived and he had been brought to Shihala around 26 December. He told me that Bhutto had gone to the bungalow soon after his arrival. Bangabandhu asked him if he had also been placed in detention. Bhutto then told him that he had become president of Pakistan. Bangabandhu, laughingly, put the question to him: ‘How have you become president, when I got twice as many seats in the National Assembly?’ Bhutto was embarrassed and responded that Bangabandhu could become president if he desired. Bangabandhu replied, ‘No, I do not desire it, but I desire to go to Bangladesh as soon as possible’. Bhutto then told him that he would make necessary arrangements but needed a few days. Bangabandhu told him that he had gathered, from the conversation between the lawyers (Mr. Brohi and others) who had attended his trial some months earlier that Kamal Hossain was also held in custody awaiting trial. Bangabandhu had, therefore, requested that I be brought to Shihala. The circumstances under which I was released from Haripur and brought to Shihala became clear.

The next few days were spent in pursuing the request for arrangements to go to Bangladesh. It was clear that since over 90,000 Pakistani military personnel were prisoners of war in Bangladesh, this would ensure Bangabandhu’s safety and early return. The question, therefore, was of expediting logistical arrangements. Aziz Ahmed, who was still looking after foreign affairs, came to see us. He said that Bhutto would make an announcement regarding Bangabandhu’s departure for Bangladesh in the first week of January, when he was scheduled to address a public meeting in Karachi. He said that they were keen that we should be flown out in a Pakistani aircraft, but that presented a problem since it could not fly over India. He suggested that we be flown to some third country in a Pakistani plane, and other arrangements could be made from there. He suggested Tehran. We discussed this matter. Bangabandhu indicated that this was inappropriate as a transit point, as it would present an opportunity for political pressure to be exerted regarding Pakistani concerns. We should, therefore, insist on being flown to a neutral capital such as Geneva or Vienna. I suggested this to Aziz Ahmed, who responded negatively. When I kept pressing him to come up with an alternative suggestion, he proposed London. We readily accepted it since we had learnt over the radio that London had been an active centre from which support for the liberation war had been pursued. We were told we would be flown to London within the next few days; the night of 7 January was specifically indicated. We were informed that Bhutto would like to host a dinner for us at the President’s Guest House before we left. We would be driven from Shihala to the President’s Guest House, and would board the plane immediately after dinner. Bhutto arrived and, after initial greetings, he requested Bangabandhu to maintain links with Pakistan. Bangabandhu replied, ‘After what has happened, and the blood spilt which could have been avoided had you listened to us. Instead you unleashed a brutal armed assault. I cannot see how any relation with Pakistan is possible other than as between two sovereign states’. After Bhutto kept pressing him to consider his appeal, Bangabandhu said he would give him a reply after returning to Bangladesh. Bhutto then came up with an unexpected suggestion: that the departure be delayed till the following morning when the Shah of Iran was due and would like to meet Bangabandhu. This was immediately perceived by Bangabandhu to be a means of exerting pressure – which he had guarded against by declining to fly via Tehran. Then another pretext was presented for delaying our departure. It was said that, since a head of state was due in the morning, the air space in Pakistan would remain closed all night.

Bangabandhu and I then conferred. I pointed out that closing air space did not mean that a gate was locked and could not be opened; all it meant was that all flights had to get specific permission from air traffic control. Bhutto could issue instructions for that purpose. Bangabandhu then turned to Bhutto and said that he should ensure permission for our flight to leave that night; insisting that he did not wish to meet the Shah, and that we should be transported back to jail immediately if our departure could not take place after dinner as scheduled. Bhutto, realising the annoyance he was causing, conferred with his officials and then said that a plane would be instructed to be flown over from Karachi to ensure our departure after dinner. Bangabandhu was pleased to learn this.

Hearing this, I immediately suggested to Bangabandhu that he ask Bhutto to arrange for my wife and children, who had been in Karachi while I was in jail, to be put on that plane. It was like asking for a miracle, but it happened because Bhutto clearly did not want to refuse a request from Bangabandhu. Bhutto instructed the officers present to telephone Karachi and put my family on board. I learnt from Hameeda that they were given an hour’s notice before being taken to Karachi airport, having packed only a few clothes. They were not told where they were being taken, but were given the impression that they were being flown to Rawalpindi. It was only after they were on the plane that they were told that Rawalpindi was not the final destination, and that they were to be flown elsewhere from there.

We were driven to the airport. Bangabandhu was escorted by Bhutto up to the plane. As I entered the aircraft, I saw my wife, Hameeda, and Sara and Dina, my daughters, seated there. We were overjoyed at our reunion. I remember one of the first remarks of my four-year-old precocious daughter, Sara, who asked, ‘Were you in jail because you took part in the election?’ We spent much of the journey learning about the events of the nine months that we had been separated.

We were briefed that no announcement would be made about our plane journey until we were an hour away from London. The plane would inform the countries we were flying over that this was a Pakistani aircraft carrying ‘strategic cargo’. As we approached London, a message would be sent to the British authorities to say that Bangabandhu was due to land at London’s Heathrow airport around seven in the morning.

As we were escorted from the plane to the VIP lounge in London, I cannot forget the remark of the British police officer on duty outside the VIP lounge. Suddenly addressing Bangabandhu, with tears in his eyes, he said, ‘Sir, we had been praying for you’. It gave us some sense of how people over the world had been supporting our liberation struggle.

As I entered the VIP lounge, I heard an announcement that there was a telephone call for ‘Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’. Bangabandhu asked me to take the call. It was from lan Sutherland of the British Foreign Office. I remembered meeting him in Dhaka in February 1971. He later retired as Sir Ian Sutherland, the British Ambassador in Moscow. He told me that the British government had received a message regarding our arrival only an hour earlier. He had, however, taken immediate steps to receive Bangabandhu. He had ordered a car and expected to be at the airport shortly. We should await his arrival as he had arranged accommodation and security in London. Bangabandhu told me to ask him how we could contact Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury. We were informed that Justice Chowdhury had left for Dhaka the previous day, but that the person in-charge of the Bangladesh mission was Rezaul Karim, who had declared allegiance to Bangladesh and had been assisting Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury. Before I could call, Rezaul Karim phoned to enquire whether the news he had received was correct. When I told him it was, he, too, could not hold back his emotions and said he would leave for the airport immediately.

Dr Kamal Hossain is Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of Bangladesh, an eminent jurist and one of the architects of the Constitution of Bangladesh.

This is an excerpt of chapter seven titled ‘Military Crackdown, Jail and Homecoming’ of Kamal Hossain’s autobiographical work Bangladesh: Quest for Freedom and Justice (UPL: March 2013)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments