Where do we stand?

In the last five years Bangladesh has been maintaining a GDP growth rate between six and seven percent. Consequently, Bangladesh's energy consumption has been increasing at more than eight percent per year. Electricity consumption has been increasing even faster at 10 percent per year.

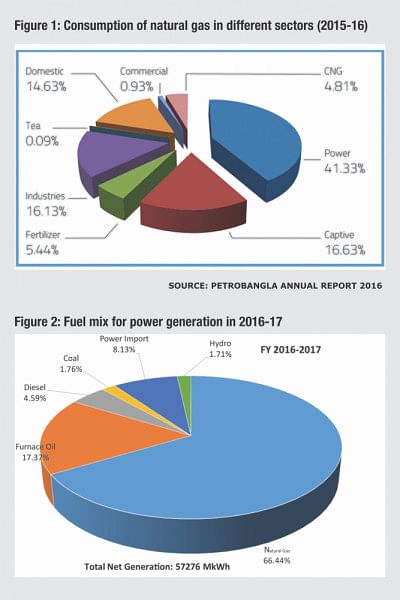

The country is heavily dependent on natural gas. The consumption of natural gas in different sectors for the year 2015-16 is shown in Figure 1. As can be seen more than 40 percent of the gas is consumed by the power sector. Additionally, nearly 17 percent gas is used by industries to generate electricity on-site (captive generation), and there are many large industries such as the urea fertiliser plants that generate their own electricity using natural gas. Therefore, approximately 60 percent of total natural gas is used for power generation.

Domestic natural gas production is less than 3,000 MMcfd (million cubic feet per day), but the demand is more than 3,500 MMcfd. From existing reserves the supply cannot be increased, and, therefore, the gap between demand and supply will widen as the demand in 2030 is projected to be more than 5,000 MMcfd. Considering a modest exploration programme where the probable and possible reserves can be brought into supply, the production of gas would still fall to 2,000 MMcfd in 2030.

If no new reserves are discovered then all proven reserves would be exhausted and the full supply would have to be met through imported LNG. The 2P (proven + probable) estimate of remaining reserves is less than 14 Tcf (trillion cubic feet). Even if the 3P (2P + possible) remaining reserve, which is 18 Tcf, is considered, the 2030 demand cannot be met. The gas resources are modest according to a USGS study (32 Tcf at 50 percent probability), and cannot be relied upon beyond 2030 to fulfil demand in all sectors.

Bangladesh has plans to expand its electricity sector, but is finding it difficult to execute the plan because of severe shortage of primary energy. In the last decade Bangladesh has been able to add very little to the natural gas reserves. Since the country's industry and power generation is heavily dependent on natural gas, Bangladesh has decided to import LNG to meet the shortfall of gas. Obviously, this will have a huge impact on the price of gas. With more and more LNG import the price of electricity produced from natural gas would increase to a level that would no longer be the cheapest option in Bangladesh. When all of the gas is depleted then the tariff for gas-based electricity will be produced from LNG.

The present weighted average tariff for gas is USD 2.5/1000 ft3. Therefore, if LNG is used to meet the shortfall, then even in the best scenario industries will have to pay nearly three and a half times the present tariff, and in the worst case scenario, which is as probable as the best, the price of gas will be more than five times i.e. the full price of LNG.

With regard to developing coal resources, no progress has been made. Concerted resistance from environmentalists is preventing open-pit mining of coal. Bangladesh is blessed with one of the finest quality coal. Not only is it low in sulphur but a good portion of it is also high-value coking coal. If open-pit mining is employed then more than 90 percent of the reserves can be extracted. Even 50 percent of our known reserves will allow 10,000 MW to be generated over 20 years. Without open-pit mining it would not be cost effective to develop these mines. Only one coal mine has ever been developed in Bangladesh with Chinese assistance at Boropukuria, and has been able to extract only 8-10 percent of the reserves in its nearly 15-year mining history.

The government has declared that mainly imported coal will be used for power generation. Depending on imported coal for 50 percent of electricity generation in 2030, as stipulated in the Power System Master Plan (PSMP) 2016, is ambitious and risky because Bangladesh does not have a deep-sea port. Three major hurdles with respect to imported-coal-based power plants can be anticipated, namely timely financing, construction of coal-receiving facilities, and coal purchase contracts.

POWER DEMAND AND SUPPLY

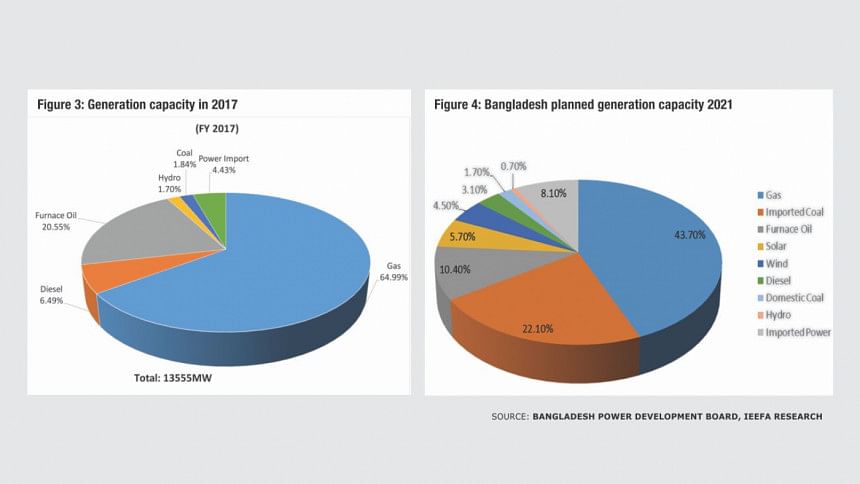

The fuel mix for electricity generation in 2017 is shown in Figure 2. Natural gas is the predominant fuel in Bangladesh, and as can be seen from Figure 2 nearly two-thirds of total electricity has been generated using this fuel. Other than the predominance of natural gas, there are two noteworthy things in the figure. The first thing to note is that nearly 22 percent electricity has been produced using liquid fuels (diesel and furnace oil). The second thing is that more than eight percent electricity came from “power import”.

The generation capacity in 2017 and the plans of the power sector for 2021 are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 respectively. Compared to the figure for 2017, it can be seen that imported coal occupies a significant portion of the pie in Figure 4. There is also doubling of power import capacity from four to eight percent. These expansions are expected to come at the expense of gas, furnace oil and diesel. Thus the challenge between now and 2021 is the successful completion of the coal projects and sealing the proposed power import deals.

COAL-BASED POWER PLANTS

Presently, three joint ventures are at various stages of implementation. The two private sector coal projects are yet to show any real progress. The total generating capacity of these five power plants is more than 6,500 MW. Of these, only the Payra Project is more or less on track, and is likely to start production in 2019. However, this project faces severe challenges with regard to coal

transportation from the ship anchored at the outer anchorage to the plant. Due to the very low draft around the plant, coal will have to be transported nearly 20km in small vessels.

Recently, the government declared that Payra will be a “power hub” where nearly 10,000 MW of power plants will be situated. Experts familiar with the siltation problems in Bangladesh consider this to be infeasible because large quantities of silt are regularly carried by the rivers and deposited at the mouth of the rivers in and around the Payra coast. They believe the cost of dredging to keep any deep-sea port in that area navigable will be prohibitive.

The temporarily shut down Matarbari Project has resumed construction. Here the project includes a deep-sea port for handling coal. The real concern here is the cost of the project and the resulting tariff. Japanese projects are usually costly, and the addition of the deep-sea port will make it even costlier. Moreover, it has faced inordinate delay in project implementation. Therefore, the financial obligations for Bangladesh are unknown. Here also the government has declared that this will be a “power hub” where more than 10,000 MW of coal and LNG-based power plants will be situated.

Matarbari is suitable for a deep-sea port and can hence be made a power hub but what is unclear is the capacity of the proposed deep-sea port. Presumably, the port for the Matarbari Coal Project will have the capacity only to accommodate the power plant. If that is so, the deep-sea port for the power hub will have to be built, which remains a financial and logistical challenge.

The Rampal power plant is progressing but at a very slow pace. It faces numerous difficulties including financing and resistance from environmentalists. The long delay in implementing the project is bound to have an adverse effect on the cost of the project. Coal transport from outer anchorage to the plant and contract to source high-quality coal are also significant challenges. The reason high-quality coal would need to be imported is the sensitive nature of the ecosystem of the Sundarbans.

LNG-BASED CCGT AND NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS

The government has announced several plans for LNG-based CCGT (Combined Cycle Gas Turbines) power plants. But none of these have reached the Power Purchasing Agreement (PPA) stage. The infrastructure challenges for these power projects are regasification facilities, pipelines to transport the regasified LNG to power plants, the CCGT power plants, and finally the extensive transmission lines for evacuating the power from remote locations to the demand centres. For the first few projects of approximately 2,000 MW, the government will probably be able to find financing and partners but to achieve the 2030 target and beyond it will be the real challenge.

The other planned fuel and capacity diversification project is the nuclear power plant at Rooppur. Construction has started but it is well known that nuclear power plant construction is extremely sophisticated and difficult; cost overruns and delays are routine. Delays of as high as five years are not uncommon. The initially announced cost has been revised upward several times, and now stands at more than USD 13 billion for the 2,400 MW plant. Most experts believe that this will cross USD 15 billion and many unforeseen logistical hurdles are predicted.

POWER IMPORT

A great achievement was the import of power from India. The cross-border electricity trade initiated in the last two years is probably the biggest success of the present government. Had it not been for power import the only viable option for generating more power would have been increased oil-fired generation. The high-cost oil-fired generation would have put significant stress on the budget. Energy trade has great potential as this region is well-endowed with significant hydroelectric potential. Both Nepal and Bhutan in the near to medium-term are unlikely to be able to consume any significant quantity of electricity generated in their countries. In such a scenario, Bangladesh plays a very important role in developing energy trade in the region.

As an electricity-importing country, Bangladesh needs long transmission lines and receiving stations need to be built here. If electricity is generated in Nepal and Bhutan, large substations to receive the electricity need to be constructed here. Depending on where electricity is transmitted within Bangladesh, one or more transmission lines originating from the receiving station would need to be constructed to transmit the electricity to various parts of the country. A station to receive 500 MW of electricity from the Indian grid is located at Bheramera. This is now being upgraded to receive 1,000 MW of power. The other entry point of 160 MW of power into Bangladesh is in Comilla. Here eventually 500 MW power would enter Bangladesh.

From the above discussion it is clear that the government's PSMP 2016 targets for 2021 will probably be met, but the 2030 targets are ambitious and are unlikely to be met. Since most of the energy will be imported, the impact on the tariffs of natural gas and electricity must be carefully managed.

Another issue is the demand for all the electricity planned. The peak demand served so far is 9,471 MW on May 27, 2017. According to PSMP 2016, the peak demand is projected to be more than 27,000 MW—nearly three times that of 2017. If all the planned projects are completed by 2030, the country will have to show remarkable economic progress to be able to consume all the power produced and imported. The last very important aspect of all these huge expenditures for the energy and electricity infrastructure is the pressure on the foreign exchange rate and debt servicing.

Dr Ijaz Hossain is Professor, Chemical Engineering Department, BUET and advisor to the government on energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emission mitigation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments