From movement to a nation

On March 30, 1971, a disheveled Tajuddin Ahmed, the general secretary of Awami League, and his associate Barrister Amir-ul Islam, crossed the border of Pakistani occupied Bangladesh into India. They were not sure of Indian reception. Though Bangladesh declared its independence on 26 March, Pakistani military junta was still internationally recognized as the legitimate government of both wings of Pakistan. Tajuddin and his associates had no legal locus standi from diplomatic perspective. Meanwhile, Bengali troops and police forces who came to control major towns in Bangladesh, were brutally crushed by the well-trained and well-armed Pakistani forces. Spontaneous resistance broke out in the country and soldiers of East Pakistan Rifles, armed police forces of East Pakistan and youth volunteers tried to liberate their localities. They were looking for a political center to guide them.

India was surprised and concerned by the rapid turn of events in East Pakistan. India is a multinational polity with significant Bengali population concentrated in the states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam, all bordering East Pakistan. Since 1967 West Bengal returned a communist dominated United Front to power and the CPI(M) the principal partner in the United Front further augmented its strength in an election held in February 1971. More importantly, since 1967, a radical Maoist offshoot of CPI(M), rechristened in 1969 as CPI(ML), stirred the countryside of Eastern India with their slogan of annihilation of class enemies. Known as Naxalites, an appellation based on the originating site of their movement, these revolutionaries shook the foundation of the Indian political system. India was aware of the presence of Maoists and communists in Bangladesh too. Thus, India was not thrilled that another national democratic revolution, with Bengali nationalism as their legitimizing ideology, unfolded just across the border. Yet they recognized that the Bengali nationalist movement in East Pakistan aimed at the independence of East Bengal only. The newly designed flag of Bangladesh indicated that they would respect the Radcliff line. Bengali leaders of Bangladesh evinced no interests in the political affairs of West Bengal and Tripura. Thus, to the pleasant surprise of Tajuddin and Amir-ul the Indian border security force staged an impromptu guard of honor for these disheveled fugitives and assured them of shelter.

BSF commander in chief Rustam Ji actually met with Tajuddin and Amirul Islam in Calcutta and transported them to Delhi by military cargo plane on April 1, 1971. On the same day, Indian parliament passed a resolution condemning the atrocities in Bangladesh. On 4th April Mrs. Gandhi, the Indian prime minister met Tajuddin and offered sympathetic hearing. On the following day, during their second meeting, Mrs. Gandhi informed them of Mujib's arrests. Sensing the urgency of the situation, Tajuddin informed Mrs. Gandhi that senior members of Awami League had formed a government and he was the prime minister. The seeds of Mujibnagar government were sown in the courageous impromptu statement of Tajuddin. The crucial need for governmental center was necessary to obtain international recognition.

Yet international situation was dire for Bengali revolutionaries. Far away from Dhaka and Delhi, in the oval room of white house, President Nixon was toying with the idea of establishing a diplomatic relationship with China, a move that would enable him to achieve a breakthrough in the cold war and to withdraw US soldiers from the battlefields of Vietnam. Aided by his brilliant but maverick national security advisor Henry Kissinger, they planned to use Pakistan's good standing with China. Nixon liked Pakistani military generals and was fond of both Ayub Khan and Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan. In 1953, during his visit to South Asia as a Vice President, he was impressed by Pakistani military leaders and since then he held them in high esteem. As a Vice President, he was instrumental in forming military alliance with Pakistan in 1954. Kissinger, on the other hand, was a hardnosed real politic man. Kissinger recognized the brilliance of the idea of neutralizing Chinese hostility and as, Gary Bass asserts (Bass, Gary Jonathan. 2013. The Blood Telegram : Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide First ed. New York: Alfred A Knopf.), was willing to sacrifice Bengalis as collateral in the larger schemes of global political realignment. Thus, both of them assured Pakistan US support in return for Pakistan acting as clandestine diplomatic conduit between US and China.

Meanwhile, China, located at the center of this clandestine diplomatic initiative of US, remained steadfastly loyal to her all-weather friend -Pakistan and viewed Bengali revolutionaries as Indian agents who were disrupting Pakistan's unity. Internationally, elsewhere the situation was not favorable to Bengali revolutionaries. From the perspectives of London, Ottawa, Tokyo, Paris and Bonn, the middle ranking powers in the world, Awami League had moral legitimacy, because of the verdict in 1971 election but no legal status. Though Soviets were sympathetic, and on 4 April 1971 Soviet President Podgorny, appealed to Yahya Khan to exercise restraint, they were not forthcoming with their support for independent Bangladesh in the initial days. They viewed such move as symptomatic of secessionism. By then, international community was already tired of secessionist war in Biafra in Nigeria and did not want another long drawn civil war in a third world country. Meanwhile, refugees, escaping Pakistani military atrocities, poured in India. Their number arose from 500,000 in April 1971 to almost 8 million by the end of August 1971. Pakistani military occupation of Bangladesh turned out to be the worst humanitarian crisis in South Asia after the partition.

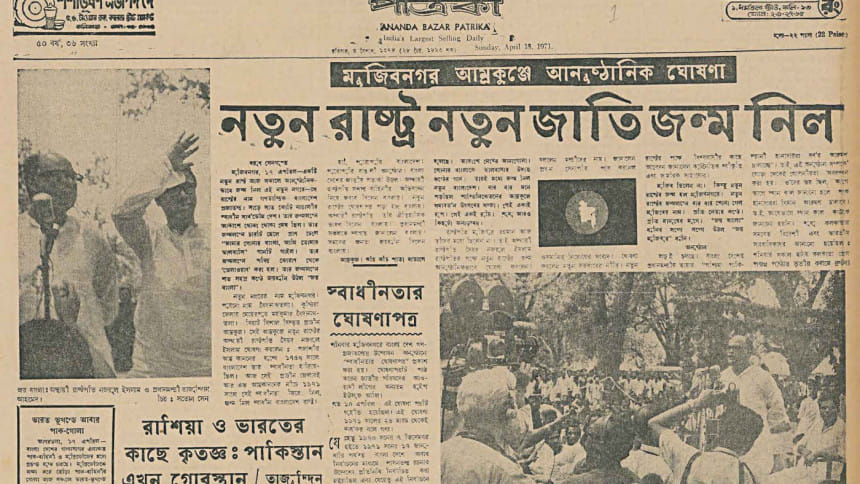

The crucial task before Tajuddin and his associates was to establish a legitimate presence in international circle as a governmental authority. The new government had to coordinate revolutionary resistance at home and obtain Indian support as well as diplomatic recognition from abroad. On April 17, in Baidyanathtola, of Meherpur district, in a mango grove, new independent government of Bangladesh was sworn in. It was a symbolic move too. Bengal's independence was lost in a mango grove on 23 June 1757 in the infamous battle of Plassey and was regained on 17 April 1971 in another mango grove.

In the early days, international journalists were not sure of the formation of the government. Peter Hezelhurst, a correspondent of London Times, who covered the liberation war extensively, wrote on 13 April 1971 in (London)Times that Tajuddin, the principal strategist of Awami League, who was rumored to be dead during the military crackdown in Dhaka, had been alive and would form a government. Soon the government in exile became known to the world through a proclamation issued on 17 April.

Western powers were obviously worried about Tajuddin, the kingpin of exile government of Bangladesh and the Prime minister. The British High commission in Calcutta interviewed Hiren Ghosh, a Congress (organization) member to collect the background information on Bangladesh leaders. According to the secret memo of British high commission, it was mentioned Tajuddin was 'unpopular lone wolf' through which 'Communist influence percolates' in the government. (Foreign & Commonwealth Office Document- Eleanor Lane to RLB Cormack 9 November 1971 File P1/14 Secret Correspondence Government of Bangla Desh in East Pakistan) Clearly, the former imperial masters were nervous about Indo-Soviet pact that materialized in August 1971. The formation of the all party advisory committee comprising NAP Bhasani and NAP Muzaffar Ahamed and Bangladesh Communist Party in September 1971 further made them nervous about the future inclinations of the Bangladesh government. Yet it was the Mujibnagar Government that acted as the legitimate government of Bangladesh.

The formation of Mujibnagar government changed the image of Bangladesh liberation war. From a movement for autonomy within Pakistan, the government in exile morphed into a political center representing the people of a newly emerging nation. Several Pakistani diplomats starting with M Hossain Ali, deputy high commissioner in Kolkata took oath of loyalty to the Mujibnagar Government. Rehman Sobhan and Abu Sayeed Chowdhury, as envoys, made favorable impression on Western diplomats. The Mujibnagar Government thus developed an independent presence in international community. The existence of Mujibnagar government enabled Bangladesh to have an independent government after the victory on 16 December, 1971. The tragic irony of Bangladesh was that in 1975 the luminaries of the first independent government of Bangladesh were murdered in a dastardly manner not by Pakistan army but by the soldiers of the very country that they brought into existence.

Subho Basu is an Associate Professor at the Department of History and Classical Studies, McGill University Montreal.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments