Enchanted Delta

Here we present an excerpt of the writer's unpublished novella, The Enchanted Delta. Nadeem, one of the main characters of the story, a talented university professor, has a sudden flashback to March 25, 1971 when he was only twelve-years-old.

For sometime Nadeem had not been able to sit down at his writing-table. He caressed with loving fingers the diary in which he had recorded his experience of the Pakistani genocide of the Bangalees in 1971. He was barely twelve then. His parents had put him in the house of an uncle who taught Physics at the university. He was given a bed and a table in a corner of their flat in Savage Road, where he lived now, in a different block. The school, established for the children of university teachers, was just next-door. It had no playground and was run by a youngish woman with flighty eyes and a harsh voice. Nadeem missed his parents and the relative slow pace of life, which he had left behind in the village. But his gifts were being recognised here in a way, which was beyond his wildest dreams in the village. He became a regular artist in the children's programmes on the radio and the television. He also wrote for the children's pages. Everyone recognised him in the streets and shops as the prized boy from the village. His uncle, a cousin of his mother's, Hussain Ahmed, shared with Nadeem a similar background. He had also come from the village to stay with an uncle. Hussain Ahmed had stood first in the first class in Physics Honours. The three years he spent in Cornell, where he went on a government scholarship, had given him the extra glamour, which brightened an already brilliant career. He made much of the boy and never allowed Nadeem to feel unwanted. A good-looking man, when not immersed in his books and experiments, he listened to Indian classical music. He was also a close friend of Selina's parents. His wife and Selina's mother were distantly related as well. The entire country was in a ferment over the non-co-operation movement launched by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. February, as usual, was fiery. March came with a lull of pent up tension, which could explode any minute. Nadeem longed to join the crowds in the streets. When no one was around, he watched his own face in the mirror as he improvised a fiery speech directed against the Pakistani military junta. But his uncle kept a close watch on him.

On the evening of the 25th, an old associate from Cornell, Frank Wilder had dined in their flat. Hussain's wife Sarah took out her lace tablecloth and rarely used cutlery, to set the table. She had made Nadeem collect some pink wild flowers, which she arranged in a brass bowl. Nadeem had never seen anything like this before. Two olive-green candles were lit in the candelabra.

Sarah put on a Ravi Shankar on the recorder. Nadeem, captivated, lapped up the entire scene with eager eyes. He decided he would like to entertain like this when he grew up. Sarah herself in a Lady Hamilton sleeveless black blouse and light blue silk saree looked ravishing. Nadeem adored his aunt as she went about in a flurry, baking and cooking and constantly consulting her cookery book. She was trying out some European dishes. She had made a fish soufflé with cheese and tomatoes. She had gone to New Market herself to pick the freshest Bhetki. She also made a fabulous Russian salad with eggs and mayonnaise. For pudding she had baked a soft orange-cake to be taken with fragrant custard. These exotic dishes had opened a new world to Nadeem. The university flat, dusted, cleaned and decorated with fresh leaves and flowers, looked out of the world.

Dr. Wilder smelled Sarah's sandalwood scent and the inviting flavour of the baked dishes from the kitchen and gave a broad smile, "I say Hussain, you don't live like a poor Bangalee!"

Nadeem was all ears, trying to understand the English spoken in a different twang. Looking at the boy Frank Wilder joked: "You devil! How did you produce a strapping twelve year-old out of the blue? You got married only last year."

"He is my nephew. A brilliant chap. He can give you each detail of American history if you care to question him. Hussain stated with immense pride."

Nadeem had eaten in the kitchen, afraid of the instruments, which he did not yet know how to handle. He helped his aunt to bring in the steaming dishes and then lay them symmetrically on the dining table, according to her instructions. He watched with fascination the skill and briskness with which the three handled the knives and forks. He made up his mind to be able to do the same, some day in the bright future, hardly anticipating that the very existence of his race would be in jeopardy, that fateful night of the 25th of March 1971. After the meal they sat in the veranda. Sarah said: "Frank, I am afraid you won't like my coffee. I don't have a percolator. I have made some Chinese green tea."

"With Jasmines," Nadeem ventured to put in these two English words.

"Excellent! Excellent! You Bangalees are marvellous people. No American could have served a Bangalee dinner like this."

"Sarah has never been out of this country." Wilder was amazed by Hussain's words. The entire dinner had a French flavour, which he loved. Sipping the green tea he winked at Hussain: "Some style, old guy!"

Nadeem almost threw up the green tea, which he had taken stealthily in a glass. But the grown-ups seemed to relish it. Wilder asked for another cup, remarking: "The Chinese have a habit of filling your cup again and again."

"Sorry, that's what I should have done," Sarah said in her perfect convent English.

Hussain lit a cigarette and suddenly the entire horizon reverberated with violent sounds, the like of which they had never heard before. Frank Wilder would have left in a minute or two. Red flames and smoke usurped the tranquil sky. They quickly closed the doors and windows and moved inside.

"Sounds like machine guns and mortars," Wilder stated.

Hussain picked up the phone. It was dead.

"I think I hear tanks," he said, the next-door neighbour, Mr. Hamid Hossain who worked in the English Department came in through a side-door, which had been left inadvertently open.

“Please shut all your doors," he said.

"This is an army crackdown, anything can happen."

He rushed out and Sarah closed the door behind him with trembling hands. Nadeem knew she was with child. He said to his aunt, "Why don't you lie down. I'll clear the table."

She embraced him impulsively and said: "No my darling - just be quiet - don't move!"

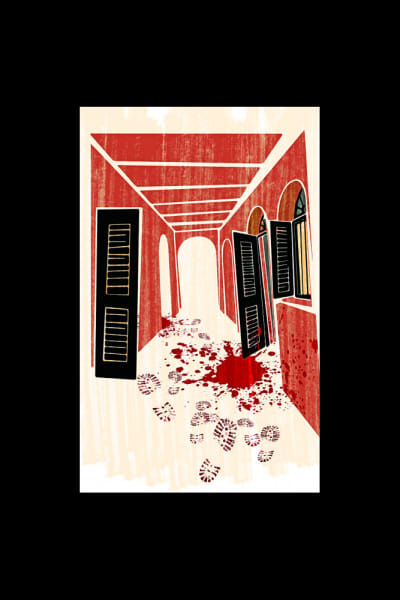

The day's hard work, and the shock of this unexpected violence must have made her nerves snap. She fainted; her husband picked her up and put her in bed. The two men and one boy sat up all night. Towards daybreak they heard footsteps. Theirs was a third floor flat. On the ground floor lived Dr. Thakurta, a senior Professor of the English Department. The noise of shooting seemed to come from that direction. Someone knocked on their door. It was Hasan: "They've shot Dr. Thakurta. He is lying in a pool of blood!"

"What? Has your Federal Government gone mad?" Wilder screamed in anger.

Hussain was about to rush downstairs. Nadeem gave out a wild cry: "Mama (Uncle), please don't go. They are going to kill us."

Hasan advised: "You mustn't move. They are still shooting, we must wait quietly."

The whole day passed in unbearable anxiety and grief. Curfew had been announced through the radio. Wilder had borrowed a car from one of his diplomat friends. It was parked outside, but he could not leave. The sound of shooting had merely subsided only for a while. It began again in full vigour almost bursting the eardrums.

The red glow in the sky and the heavy roar of mortars continued. Towards sunrise the furore seemed to subside.

Hussain was busy tending Sarah. Nadeem took her a cup of warm milk. Together they washed her head. They found Wilder in the kitchen trying to make tea. Hussain took over, asking his guest to leave it to him. Wilder went for a wash. A heartrending moaning sound rose from downstairs. Nadeem covered his ears and said: "It must be Dr. Thakurta's wife."

Hussain's face was red with anger. As he made tea he said: "You see, Frank, we have allowed a pack of wolves to rule us. We Bangalees are too busy with poetry and music. What we need now is military training."

During a recent convocation of the university, when a leading scientist Dr. Kudrate Khuda had announced the need for martial lessons for the Bangalee youth, the audience was a bit taken aback. Now everyone understood the significance of that counsel. The curfew was lifted the following morning at about eleven. Wilder said to Hussain before driving off: "I'll come back with provisions. I have seen everything. I'll report all this to the Herald Tribune."

Hussain pleaded with him: "Frank, please don't come back here. We may not be here when you come. Don't take me amiss. I'll contact you if I can. These are very bad times; goodbye, my friend."

Nadeem had liked the blue-eyed physicist; they shook hands. As Wlder's car left, their eyes fell on the blood streaming from Dr. Thakurta's flat into the porch. Hasan was locking the front door. He whispered, "He has been taken to Medical College. We have hidden his wife and daughter as best as we could. Now we must buy some provisions before the curfew is imposed again."

Hasan's clothes were smeared with Thakurta's blood. Suddenly Hussain lost his nerve. He sat down on the steps and started howling and sobbing uncontrollably. Nadeem had never seen his uncle break down like this.

Hussain wailed: "Thakurta was such a wonderful man. He was Sarah's teacher. Sarah will never recover from this. Please don't tell her anything. She might have a miscarriage. As it is her condition is bad."

Tears streamed down his face. He had torn some of his hair-- Hasan and Nadeem held him from both sides and took him upstairs; the dishes lay on the table, the flowers had withered. The candles had lost their shape. The festive atmosphere of the previous evening had changed into a general appearance of hopelessness and disorder. When Hasan left, Nadeem, sitting between Hussain and Sarah, felt he had a lot of responsibility towards this couple, who had sheltered him with such loving care. He stroked his uncle's back, bent with grief and bewilderment and said firmly: "Mama, we cannot stay here. We must not stay here, let us go to Muradpur, to my parents."

Sarah, who had recovered a little, said to her husband: "He is right, we must go."

"How can we? The army is everywhere."

"We'll dress like poor villagers," said Nadeem.

Briskly they poured mustard oil over their heads, to make their hair look sticky and rustic. They put on lungis. Sarah took out her cheapest sari and wound it around herself in the village manner. They made bundles of onions, potatoes and rice. It was now the evening of the 27th. Quickly locking the front door they stole out of Savage Road. Near Jagannath Hall, the hostel for Hindu boys, there was heavy military patrol. When confronted by the army Hussain and his wards opened their bundles and offered the potatoes and rice. They wailed and kept pleading, "Sir, please take all we have and let us return to our village."

Mistaking them to be absconding house-help who were too simple to be dangerous, the soldiers let them off saying impatiently: "Go! go-get out of our sight, Bangalee buggars!"

Hussain got into a baby-taxi with his family. Their village, not far from Narayanganj was reached before mid-night. Muradpur village did not look the tranquil place it had been. They saw half-burnt homesteads and cornfields. Smoke had enveloped the entire horizon. Nadeem's parents were in bed. Hearing their son's voice they came out with a Hurricane lantern. The women broke into sobs. The men stood in stony speechlessness. No words could express their predicament.

Nadeem's mother awakened Golapi the housemaid and got about preparing a simple meal for the weary travellers. She had water drawn from the pond. They snatched a couple of hours' sleep towards dawn. After a fortnight Hussain had managed to sneak out to India with his wife. From there he flew to the United States where he settled down for good.

It was Nadeem who was now installed in a Savage Road University flat. Hussain came on vacation last year and stayed with Nadeem. Frank Wilder, a renowned name in Physics, shared the Nobel Prize with another countryman. Nadeem had seen the carnage caused by the Pakistan army in Dhaka and in his own village. He was then only twelve. Yet he had been able to force the Hussains to leave their Savage Road flat from where, just when victory was at the door, in December, Hamid Hossain and several other teachers were killed. Hussain Ahmed had escaped the butchers by going to Nadeem's village and then to Calcutta.

Born in Faridpur on February 16, 1936, Razia Khan, novelist, poet, literary critic and short story-writer, was an avid reader of English and Bangla literature from an early age. She joined the Dhaka University as a lecturer in 1962 where she taught until her retirement in 2003 as a Professor of English Literature.

Her first collection of English poems was published in 1976 under the title Argus Under Anaesthesia. Cruel April, her second volume of English poems published in 1977. Her collection of Bangla poetry Sonali Ghasher Deshe came out in 1977. She has also written several novels in Bangla besides Bottolar Upanyash including – Anukalpa, Protichitra, Padobik, He Moha Jibon, Chitrakabya and Draupadi (also translated in English by the author). She has also written Tinti Ekankika – three one-act plays and translated in English, Zahir Raihan's 'A Different Spring'.

Her awards include the P.E.N. award as a student playwright in 1956, the Bangla Academy award for her contribution to the Bangla novel in 1974. She also won the prestigious national award Ekushey Padak for Education in 1997.

Razia Khan died in Dhaka, Bangladesh on December 28, 2011.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments