The Gaze as 'little object a': Bangladesh at the United Nations in 1971

'Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that defences of peace must be constructed.'

−UNESCO, The Constitution

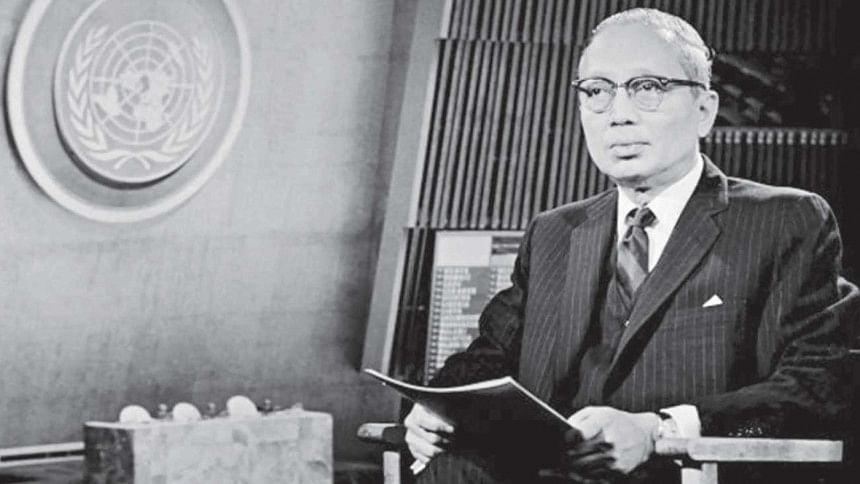

have two reasons to write this short article. In the first place, it gives me a good measure of pleasure to draw attention to a book I admire, which is otherwise little discussed. It contains a valuable matter on the formation of Bangladesh as a nation state. U Thant (1909-1974) was the third secretary general of the United Nations. His nomination there was both a reflection of the Cold War era as of some growing visibility of darker nations in that era. A practicing Buddhist, he was well known for his personal modesty, and as one admirer writes, he meditated everyday 'with a view to cleansing his mind of impurities and cultivating desirable qualities.'

On the sudden death of Dag Hammarskjold in September, 1961 U Thant was appointed acting secretary-general shortly afterwards. In addition to completing Hammarskjold's tenure, the wind carried him up to December 1971 to fulfill his own two terms. A few years later, in 1974, U Thant died rather prematurely at 65. It was in the last year of his term that the Bangladesh crisis broke out.

U Thant took a rather dim view of things, being a prisoner of his outlook. It was impossible for him to take the cause of Bangladesh easy. He nevertheless provides us with a window to limits of world order and its accompanying outlook, which we call the gaze there. For it is typical of U Thant to write in his memoirs: 'As a friend of both India and Pakistan, and as one who was brought up to admire the cultural heritage of both countries, I felt a sharp pang of distress at the tragic turn of events.' Despite all sharp pangs it, however, never became possible for him to see through the fog even years after the event. He goes completely against the current: 'The Indian conquest of East Pakistan was complete and the new nation of Bangla Desh was born.'

My other reason for taking this up is its theoretical import. Some have taken a rather dim view of U Thant's record in light of his taking a rather limited view of the UN, of what it can achieve in a world where last words belong usually to its competing member states. His memoirs reinforced that view to some extent. For us, this provides a welcome opportunity to ask once more the good old question: 'What is international law?' We may submit the Bangladesh case as pointing an important limit to the concept of international law as we know it. U Thant's work bears testimony to that limit.

'All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic and social and cultural development,' –provides the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. But in these and other international legal texts it is not clearly defined what constitutes a 'people' for the purposes of claiming this right. South Asia in 1971 provides us with an illustration.

U Thant poses a truly 'fundamental question'. In his memoirs U Thant writes: 'While there is absolutely no doubt about the brutal character of Pakistan's military suppression of the Bengalis from March 25, 1971, onward—the savagery of the atrocities committed have few parallels in history—there is considerable doubt about India's role in this grim episode.' In U Thant's view, therefore, what you have here is something of a paradox. If India, on the one hand, is held guilty of violating the doctrine of noninterference in the internal affairs of another state, on the other hand, Pakistan could equally be held guilty of violating the rights of seventy five millions of her own citizens, of whom some 10 millions crossed over to India. India alone had to bear the burden of it all, sustaining millions of aliens on her territories. 'If India is held guilty under the law,' U Thant approvingly quotes an Indian scholar as claiming, 'it provides no answer to what she should have done.'

Another Indian scholar, also quoted by U Thant, takes an opposite stand. He is led to think, 'a settlement between the Bengali Muslims and Pakistan would have been arrived at even after the military suppression if India had not helped the Bengali insurgents to organize attacks on East Bengal from her territories.' 'By showing an obvious desire to profit by troubles,' according to this grandiose thinker, 'India stiffened the back of the Pakistan government.'

These obtusely opposed views also happened to dominate UN debates in 1971 and thus resulted in a political-diplomatic sclerosis of which U Thant speaks in so severe terms. He accuses the world organization of certain ineffectiveness and does not spare it the pity it deserves either. 'No matter how history judges the motivations of India or Pakistan,' U Thant notes, 'their conflict had a tragic result for the international community: a major victim of the war was the United Nations and the principle of international co-operation it embodies.'

The UN secretary general is constrained to take the cause of Bangladesh as one more blow on the face of the world organization. He, however, is fair enough to agree that there is some justification for this humiliation, though he doesn't go all the way to trace the origin of this impasse. U Thant is not able, however, to admit the cause of Bangladesh (or East Pakistan, as the land was then known) as part of the answer. The matter is perhaps obvious. But U Thant apparently never found a way out of the paradox. Let's see why. 'For throughout the struggle, the United Nations had made no move to act; my pleas and warnings to the Security Council, both privately and publicly, fell on deaf ears,' writes U Thant. 'The Council,' he adds, 'was immobilized, both by the refusal of the parties directly involved (India and Pakistan) and by the major powers, to face up to their obligations under the Charter to confront the issues forthrightly.' Some other scholars have concluded that the United Nations in 1971 was a forum for discussing, but not resolving the conflict.

The crisis in Bangladesh had its root, U Thant readily admits, 'in the deep split between the Punjabis of West Pakistan and the Bengalis of more populous East Pakistan.' The extraordinary victory of the Awami League, the leading autonomist party in East Pakistan, in December 1970 elections precipitated the final crisis. It supplied the immediate cause. The Punjabi authorities of West Pakistan suddenly discovered that what the Awami League really wanted was not autonomy but secession. On the night of March 25, the president of Pakistan ordered military action; he called in the army 'to maintain law and order'. The news remained no secret, despite all press censorship. Streams of refugees began to flow into neighbouring India. Pakistan blamed it all squarely on India. It accused India of having incited the Bengalis and alleged that Bengali 'freedom fighters' were receiving military training on Indian soil.

‘The problem was compounded,' according to U Thant, 'by the extraordinary apathy of the Security Council, which was due to the fact that neither India nor Pakistan wanted action by the United Nations. Because each party insisted that the conflict was an internal affair, none of the permanent members of the Council would support a call for a meeting.' Thus the United Nations remained immobilized throughout the duration of the Bangladesh crisis, except in the face of the endgame.

U Thant offers a rather feeble apology. He writes: 'Some people have argued that I should have invoked Article 99 of the [UN] Charter, under which a Secretary General may bring to the attention of the Council any matter he considers a threat to world peace. But given the negative attitudes of India and Pakistan, I doubted that a majority of the Council members would have agreed to hold a meeting; and even if they did, no agenda could have been adopted because Pakistan would have argued that international peace was not involved—that is, that the dispute was purely a matter between Pakistan and the Awami League.' Why didn't he invoke Article 99 then? 'If I had then been accused of having invoked Article 99 on a “false” premise, my utility as a prospective mediator would have been seriously jeopardized,' U Thant answers back.

On 20 July, that is some four months after the crisis erupted, U Thant found occasion to distribute a confidential memorandum to the Security Council members, warning them of a possible outbreak of war. In August he invokes Article 99, albeit implicitly, by making his confidential memorandum public. The Security Council, all the same, did not pay heed. 'Yet it was not until December 4, over four months after my warning, that the Security Council met,' regrets U Thant, 'and even then, the Council was unable to act: there was not even the shadow of a consensus whether the dispute involved India and Pakistan, or West Pakistan and East Pakistan, or India, Pakistan, and “Bangla Desh”.' Thus the Secretary-General had to turn to other important matters. “I therefore had to confine myself to the humanitarian aspects of the problem, and in May, I organized an international aid program for the refugees in India, designating Prince Sadruddin Agha Khan as its high commissioner.'

The Security Council never met on the issue until war between India and Pakistan broke out early in December. In response to Pakistan's air attacks on 3 December, India formally declared war on Pakistan, thus precipitating a spate of resolutions in the UN Security Council. There were as many as twenty-four resolutions submitted by individual member states or by coalitions of members in matter of two weeks. Debate, however, focused on two resolutions submitted by the US and the USSR respectively and another by eight member states. 'From the start,' according to U Thant, 'it was clear India would not agree to a cease-fire and withdrawal.' In addition, there was a bitter clash between the USSR and PRC over 'whether to invite representatives of secessionist Bangla Desh to address the Council.' Even such a mild resolution moved by the USSR—'which did not ask for a cease-fire, but merely requested Pakistan to "cease all acts of violence by Pakistani forces in East Pakistan”—failed to pass.'

The United States moved a resolution for an immediate cease-fire and the withdrawal of Indian troops from Pakistan held territory, i.e. Bangladesh. The USSR argued that implementation of the cease-fire should be linked to a political resolution of the crisis in Bangladesh. The third issue, as hinted above, was a call for the Bangladesh government in exile to be invited to participate in the Security Council proceedings.

The only resolution adopted by the Security Council during the war was one proposed by Ambassador AA Farah of Somalia on December 6, a day on which India formally recognized Bangladesh, referring the issue to the UN General Assembly for discussion. The General Assembly met on the night of 7 December and by a vote of 104 to 11 (with 10 abstentions) adopted a resolution calling for a cease-fire and a mutual withdrawal of troops from both sides of the border. The resolution did not end the war. It, nevertheless, went on. 'The good thing about a General Assembly resolution,' as an Indian Government spokesman in New Delhi put it then, 'is that it is recommendatory, not mandatory. It is one thing to vote, but another to grapple with a complex situation.'

U Thant wanted to save Pakistan even till the last day. His gaze comes out clearly in the following remark. His could hardly be distinguished from the US position. 'On the night of December 7, the [General] Assembly approved a resolution urging India and Pakistan to stop fighting and pull back their troops. It was essentially the same as the resolution vetoed in the Security Council by the Soviet Union. The vote was 104 in favor, 11 against, and 10 abstentions, India, Soviet Union, and other East European countries voting against it. Thus, the overwhelming majority emphasised the isolation of India and the Soviet Union, as the conviction grew among the members that the United Nations must immediately take some of sort of action.'

It was only on 21 December, after the Pakistan Eastern Command surrendered in Dhaka and also in the wake of a cease-fire agreement arrived at independently by India and Pakistan, that the Security Council finally passed Resolution 30 demanding that cease-fire remain in effect until troop withdrawals had taken place and called on both sides to treat prisoners and enemy civilians properly as specified by the Geneva Convention of 1949.

Thus 'the right of all peoples to self determination' in the sense of having the right to establish their own political system and own internal order; to freely pursue their own economic, social, and cultural development; and to use their natural resources as they deem fit is not a self-evident right. It has, in other words, to be fought for and won over.

......................................................................

The writer is Professor, General Education Department, ULAB.

References:

1. U Thant, View from the UN (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1978).

2. Richard Sisson and Leo E. Rose, War and Secession: Pakistan, India, and the Creation of Bangladesh (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments