FROM SHEIKH MUJIBUR RAHMAN TO OUR BANGABANDHU

As Bangladesh steps into its 46th year as an independent and sovereign nation, it is celebrating its vast achievements,while contemplating the intricate mechanisms needed to address its problems. Nevertheless, how can Bangladeshis ponder about the positives and negatives of their country, without honouring the man whose vision and voice drove the common people into establishing their inalienable rights of self-determination and freedom? It surely cannot. During the month of March, we not only celebrate the life of an iconic political figure, but pay homage to someone whose reach goes beyond the mere avenues of political division. As Bangladesh commemorates its Independence Day on March 26th, we simultaneously rejoice the life of the one and only Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Once an aid to Sheikh Mujib, Barrister Moudud Ahmed now serves as a senior leader in the BNP. He had the unique ability to observe Bangladesh's Founding Father from a close proximity during the late 1960s and early 1970s. In his book, “Bangladesh, era of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman”, Mr. Ahmed refers to an articulate description of Bangabandhu. He said “More pragmatic, efficient, capable and dynamic political personalities than Sheikh Mujibur Rahman might have emerged or may emerge, but it will be very difficult to find someone who has contributed more to the independence movement of Bangladesh and the shaping of its national identity”. In reality, if one is to look at the career of Mujib, it was in his tenacity and willpower to sway political messages and movements which made him into this nation's most discussed personality. There were indeed more educated individuals in East Pakistan's political circle, than Sheikh Mujbur Rahman. Yet as Moudud Ahmed rightly points out, there is little to no doubt in the minds of the citizens of this country that the influence of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in regards to the construction of our national identity and our liberation struggle, is more profound and significant than any other national figure. Mujib did not become the Father of the Nation in one day. He did not make Bangladesh in one day. A series of key events and special moments made him who he was, and by extension gave birth to our country. It was indeed the journey of an individual which stemmed towards a sovereign Bangladesh. Every time the Pakistani leadership faltered, Mujib took the stage and stood tall. Every time democratic principles were threatened by the likes of Ayyub Khan and Yahya Khan, Mujib retaliated with a vociferous democratic platform.

In 1947, the Pakistani Government announced that Urdu, and only Urdu, would be the state language of Pakistan. This naturally angered the large Bangali speaking population of the young nation. Mujib, who was still a young protégé of the iconic Husseyn Shaheeed Suhrawardy, took a key role in encouraging activists to launch strikes and protests against what many thought was an audacious decision. Senior Bangali leaders of the Muslim League, a party of which Mujib was a member, decided to break away from the traditionalist political establishment, and formed the Awami Muslim League in 1949. The likes of Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, and Suhrawardy were political celebrities to the likes of Mujib, and as such the Muslim League's prominence in East Pakistan, especially amongst the youth, was on the wane. The 1952 Language Movement ensured the foundation of the basic norms of Bangali nationalism, an ideology which Mujib tried to instil in the young leaders of the party. Elected as the party's general secretary in 1953, Mujib focussed on expanding the grassroots organisation of the renamed Awami League, whilst Suhrawardy aimed zto bridge the gap between the socialist wing of the party and established mainstream figures. It was a working relationship which ensured that Mujib had a direct line to Suhrawardy, and as such one which prospered right until the latter's death. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had surely caught the eye of the Bangali leadership in East Pakistan.

The late 1950s witnessed Mujib getting a glimpse of what governance was like. As a member of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan and a coalition Government Minister, he understood the needs and demands that the people of East Pakistan required immediately. He vociferously observed as the increasing divergence between East and West Pakistan, in terms of economic, social, cultural and political issues, became evident. In 1958, when President Ayyub Khan suspended the Constitution, Mujib was arrested and imprisoned until 1961. In 1963, tragedy struck. His beloved mentor Husseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy had passed away. If anyone had a unique and singular effect on our Father of the Nation, it was the towering Suhrawardy. Mujib was in all sense, in total awe of one of Bengal's most coveted statesman. Yet, Suhrawardy's death catapulted Mujib to the head of the Awami League. It is here where the transference of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to Bangabandhu truly began. In the 1964 election, the Awami League put its weight behind opposition candidate led by the spirited Fatima Jinnah. Mujib's support to Ms. Jinnah represented two broad ideas. Firstly, it showcased the Awami League's opposition to Ayyub Khan's severe violation of democratic rights. Secondly, by putting his weight behind a candidate related to Pakistan's Founding Father, Mujib internalised the notion, that given the direction Pakistan was taking as a country, the nation that was envisioned in 1947 was far from being realised. It was a smart and calculated move by Mujib the politician, and it catapulted Awami League to the forefront of Pakistan's national political life.

The 1965 War between India and Pakistan showcased the vulnerability of the Eastern wing compared to the West. The likes of Professor Rehman Sobhan and Dr. Kamal Hossain became closely affiliated with Mujib, and brought an intellectual dynamism to the Awami League. What Mujib said through his own voice and represented through his countless arrests, was brought forth in writing and journalism by intellectuals close to the Awami League. The disparity between the Eastern and Western wings was becoming an increasing concern, and as such Mujib made a bold proclamation, that too at Lahore in 1966. The famous 6-Point movement became the focal structural basis for the East Pakistanis upcoming struggle in the next 5 years. Through this plan, Mujib openly demanded autonomy of East Pakistan in economic, governmental, para-military and cultural terms. It was the call for two-wings of East Pakistan to exist as a pure Confederation, and nothing more. These were demands which ensured that Mujib was enemy number one for the political establishment in West Pakistan.

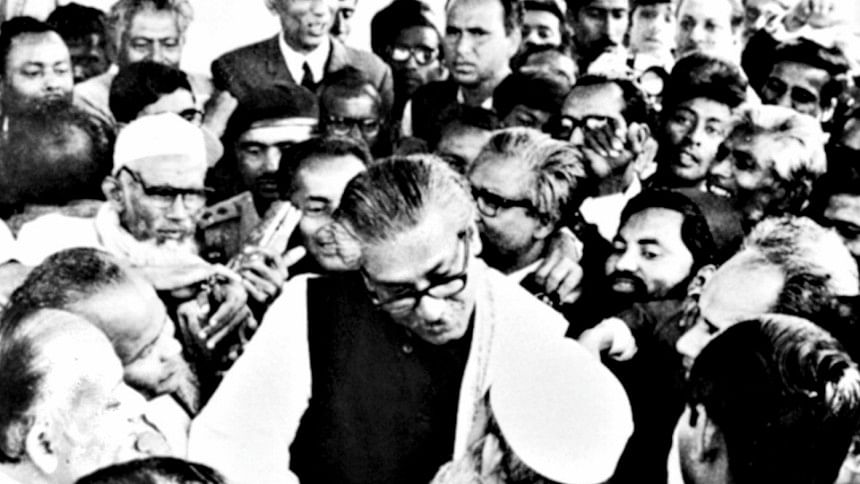

All of Mujib's efforts had culminated into an extremely crucial moment in his life. It was the infamous Agartala Conspiracy Case, a legal battle which was aimed at destroying Sheikh Mujib's political career. Instead, it turned him into our beloved Bangabandhu.The date was 22 February 1969. With a team of firebrand lawyers and the weight of East Pakistanis behind him, Sheikh Mujib had successfully fended off President Ayyub Khan's legal battle against him. The Agartala Conspiracy Case had given East Pakistanis a credible segue towards autonomy and secession. The failure to make Mujib the villain in the unravelling tale of Bangalis versus the fragile Pakistani state, ensured Ayub Khan's political demise and the subsequent rise of Bangabandhu.

The Agartala Conspiracy Case embodied a sedition case brought forth by the Government of Pakistan in 1968 against Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. After a year and a half of legal battles, the case was withdrawn in the face of public revolt in erstwhile East Pakistan. If Agartala had one unique impact in the political story of Bangladesh, it would be in its construction of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman from the leader of the Awami League to the sole leader of East Pakistan. Mujib became our Bangabandhu. He was acknowledged as a populist figure who represented the very norms of democracy which the military generals in Pakistan despised, and his post-Agartala status essentially signed the death warrant for the Ayyub-regime. The public remained in awe.

In hindsight, if one was to observe Agartala intricately, it would be ignorant to deny how the prosecution itself construed Mujib to be a hero. The case was termed the 'State of Pakistan versus Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and others'. The Pakistani Government had catapulted Mujib to the highest echelon of the political establishment, whilst simultaneously dubbing him an Indian agent. Mujib was also labelled detrimental to Islamic unity. The people of East Pakistan rejected these notions. The language of the case and the accusations brought forth formed the impression that it was a tussle between Pakistan and Sheikh Mujib. From mosques to temples, the initiation of Bangabandhu as the emblematic manifestation of the Bangali people made headlines from Dhaka to Islamabad. Ayyub Khan had unknowingly dug his country's own grave. He gave Sheikh Mujib the perfect platform to decree himself a hero for Bangalis. By refusing to accede to Mujib's 6-point Movement of 1966, and by making him an enemy of the Pakistani state, Ayub Khan had construed the modern day Bangabandhu. And the charming, charismatic and vibrant politician in Mujib took over. He used the Pakistani legal machinery's tirade on him as a forum to tell the people of East Pakistan that his beloved country was being deprived of the economic, legal, cultural and democratic justice that it deserved. He used the failures of the Pakistani Government and glorified the Agartala Conspiracy Case as representing a victory for the Bangali people. And it was surely a brilliant political move.

Bangabandhu's victory meant the automatic demise of General Ayub Khan from the Pakistani Presidency. Demonstrations, riots and protests were already underway in West Pakistan against the Ayub regime's inability to control food prices. There were widespread factions in the military which were making soundbites in their lack of approval towards their Commander-in-Chief. The Agartala Case on the other hand had moved East Pakistanis against him. By failing to make Mujib the villain, Khan resigned on 25 March 1969, after 11 years of stringent rule. His successor, President Yahya Khan, was to be the last President of united Pakistan.

In recent times, many of the co-accused in regard to the Agartala Conspiracy Case have come forward. Former Parliamentary Deputy Speaker Shawkat Ali confessed to the Jatiyo Sangsad that the charges read out to them were accurate. There are some who suggest Sheikh Mujib himself led the so called Shangram Parishad for the secession of East Pakistan. Yet, amidst all this, Bangabandhu became the hero. The Bangalis had been fed up with the civil maltreatment of East Pakistan. East Pakistanis were tired of the lack of democracy and the ruthlessness of the dictatorial regime. Democracy meant autonomy. Autonomy meant democracy. Agartala showcased why such was the only viable long-term political solution. And no one did more to find political solutions than Sheikh Mujibur Rahman himself. From deliberating with Ayub Khan to sitting with Yahya Khan, Mujib tried his best to ensure peaceful resolutions to what he very much believed were political crisis'. To try and make Mujib the villain to his own people, was simply impossible for a President who had used the military, and not his people, to remain in power for 11 years. To try and make a mockery of a man who had stood for the people, was a scheme which disastrously failed for Ayub Khan.

While it may be too naïve to suggest that the Agartala Case gave Sheikh Mujibur Rahman the final impetus to demand independence, it did show him that the central Government in West Pakistan considered East Pakistanis a plausible threat to Pakistan. As such, hoping for a united, equitable and democratic Pakistan was purely utopian for many Bangalis. The demand for secession had received the kind of traction which allowed Mujib to win a majority of seats in the subsequent 1970 General Elections. In the immediate post-Agartala period, the people said a resounding yes to Mujib, and a defiant no to Ayub. They said yes to the values inscribed in Bangali nationalism which stands tall today as a tenant of Bangladesh's constitutional structure. It is no doubt that the Agartala Conspiracy Case remains an iconic moment in the political history of Bangladesh. Our Bangabandhu was at his peak.

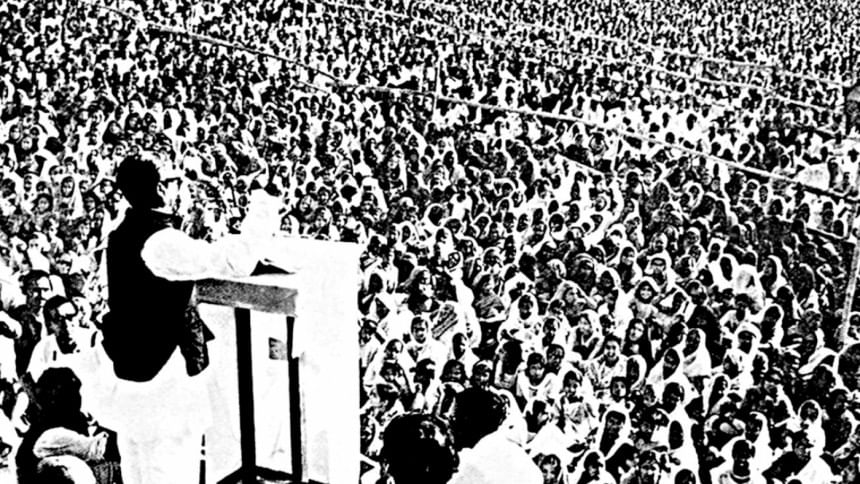

The 1970 Parliamentary Elections were a clear result of the wills and wishes of the people. Needleless to say, that it was Bangabandhu's sole passion and vibrancy which attracted East Pakistan, into voting him into office. Yet as we know now, the Yahya regime never intended to hand over power to the Prime-Minister Elect. The camouflaged discussions and deliberations was a means of getting military personnel into East Pakistan. On March 7th, Mujib effectively declared the de-facto declaration of independence. Bangabandhu was at his finest form and his people responded to whatever he asked from them. From non-cooperation to recruiting political workers, East Pakistanis remained totally indebted to their leader. And as such, when the Pakistani Military initiated Operation Searchlight on the night of 25th March and Mujib was unscrupulously arrested, the people of the newly declared independent nation took over. As the 9-month war raged on and Mujib remained confined to a jail cell in Pakistan, one would imagine that he had enough faith in his people to pull off a miraculous victory. Let there be no doubt that defeating the Pakistani military was a miracle, but it was a miracle inspired by one man and one man only. As Moudud Ahmed said in his book, it would be difficult to think about the independence of Bangladesh without recognising its chief architect.

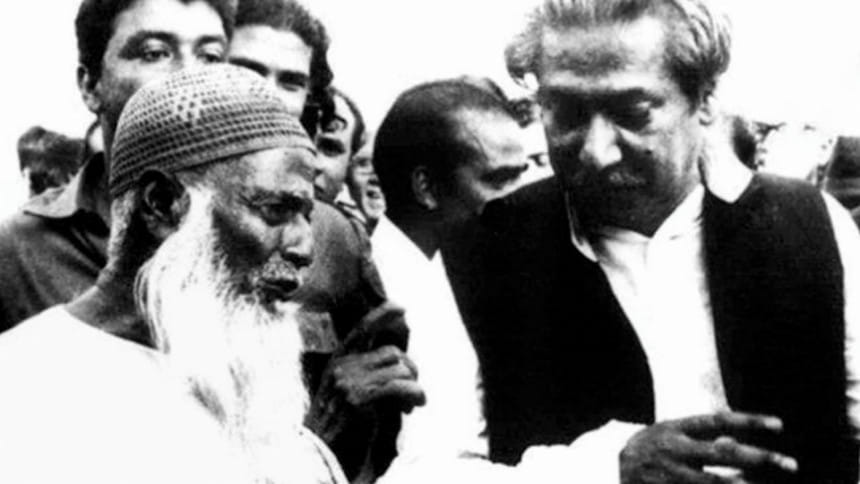

Today, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is used as a tool for political points by the Awami League. His name is a reference which garners attention, his face is plastered against all kinds of posters. He has effectively been monopolised by his beloved party. And that is the saddest possible tale for a sovereign nation such as ours. One of the great things which made Sheikh Mujib our Bangabandhu was his ability to reach out to even those with whom he disagreed. It is for this reason that even with his biggest opponents such as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Yahya Khan, Mujib remained ever cordial and dignified. It is for this reason that he thought of his own killers as his sons. If we as a country try to simply categorise him as the leader of the Awami League, we are not only demeaning him, but blatantly disregarding the history of contemporary Bangladesh. It is the simple truth that Bangabandhu does not belong to one person or one political party. He is ours. He is for the whole of Bangladesh. And his reach surely goes beyond a single political philosophy.

Another question which commonly arises is that of whether Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would have wanted independence if he had been given the position of Prime Minister. There seems to be a large divide amongst scholars regarding this subject. But first, it is significant to recognise that we as countrymen cannot be rigid when it comes to underscoring our beliefs. Intellectual discussions and debates are healthy for a modern society, and analysing our Founding Father's life is an extension of such. However, to those who question Mujib's aim for independence, one should refer them back to the contents of the 6-Point Movement. It was a clearly constructed, yet peaceful mechanism, which would bring slow and constitutional changes in the structure of the Pakistani state. It was a form of proposed confederation whose ultimate destination would be an independent Bangladesh. Now did Mujib foresee the kind of war which Yahya Khan initiated? One doubts it. His entire efforts during 1970 and 1971 were based on a non-military and democratic transference of legitimate authority, and when he realised that this was being prevented, he did whatever he could to find a diplomatic solution to the crisis. As any great statesman, Sheikh Mujib did not want a war and for that we should recognise his gravity as a political leader. But when it came to it on March 25th, Mujib left the country knowing that he had done enough to inspire his people to take up arms and defend themselves to the best of their ability.

Today as we celebrate Independence Day, we look forward to the great years lying ahead for our nation. We recognise our martyrs and those men and women who had tirelessly worked to get Bangladesh independent. However, we must express our gratitude to a man who loved his countrymen more than he loved his family and himself. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman became Bangabandhu for a reason, and we as Bangladeshis will do very well to celebrate him for who he was-an icon, a visionary and this country's greatest leader. Bangladesh did have many architects. But it had one chief architect. One without whom the plan for a sovereign Bangladesh would never have been set in motion. Thank you, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, for what you have given us. We hope that we as citizens are making you proud and will make you even prouder in the years to come.

The writer is 3rd year undergraduate student of Economics and international relations, University of Toronto.

E-mail: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments