The first resistance against Pakistan: March 19, 1971

“Don't leave me alone, make sure I am with you”, that was what Lieutenant Mokhtar Kamal Chowdhury told Second Lieutenant Ibrahim. The time was about 5pm, March 27, 1971. Mokhtar Kamal was a doctor. In military language he was the Regimental Medical Officer (RMO), of the battalion. Ibrahim was the youngest officer in the battalion. Both being junior officers, Ibrahim and Mokhtar were usually spending their time in the office of the Adjutant of the Battalion, if there was no other duty for them. While manning the office, Ibrahim's duty was to monitor the telephone, receive messages coming through the wireless or signal center, forward those to the relevant person, remain aware of the various important activities in the battalion itself, and the like. A very important duty was to ensure that no non-Bengali officer of the battalion could use the telephone or the wireless to communicate with anyone outside the battalion. The battalions of the East Bengal Regiment (EBR)had individual nicknames. The First Battalion was the known as the Senior Tigers, the Second Battalion was called the Junior Tigers, the Third Battalion was named Minor Tigers, The Fourth Battalion the Baby Tigers, and so on. We are talking of the Second Battalion of the EBR (Second Bengal) which had been passing immensely busy time for the last 10-12 days, if not more.

In keeping with the tradition of battalions, the junior most officer of the battalion would be the 'Intelligence Officer' (IO) of the Battalion and would usually be available to the Commanding Officer (CO) of the battalion at very short notice, irrespective of the time of the day or night. Not all infantry battalions have a Regimental (and resident) Medical Officer always. But the Second Bengal had a resident doctor, it being located in an isolated place, many miles from the nearest military hospital, in Dhaka. The battalion was located at the palace of the Bhawal Raja at Joydevpur which was a Thana headquarters in the district of Dhaka, located about 30 kilometers North of Dhaka. Since 1984 it has been the headquarters of Gazipur district. During the days of March 1971, the RMO would often be offering a helping hand to one or the other officer, because his medical commitments were very few. The battalion was intensely busy every day of the month of March. It revolted against the Pakistan government on the 26th of March 1971 and prepared itself to abandon the accommodation in the Rajbari on the evening of March 27. There could always be a slip between the cup and the lip, so the doctor of the battalion, Lieutenant Mokhtar Kamal did not want to miss the occasion. He warned Ibrahim likewise. Both Mokhtar Kamal and Ibrahim had taken oath at the time of their commission in the Pakistan Army “to defend the Constitution of Pakistan, to remain loyal to the President of Pakistan, to carry out the orders of any superior officer even to the peril of life.” Now, on the early hours of the March 26, 1971, Mokhtar Kamal and Ibrahim were revolting against the Pakistan Army and the President of Pakistan. The young educated readers of this column would surely be able to envisage the scenario: Mokhtar Kamal and Ibrahim were revolting, mutinying! Indeed, the entire Second Bengal was revolting and mutinying. It is but natural to enquire, why would disciplined soldiers revolt? Therefore, let me go back in history to a couple of days or weeks of March 1971, and present a review of the events to the readers, majority of whom are likely to be Bangladeshi generation, that is, born in, or after, 1971.

The elections to the national assembly of Pakistan and the provincial assemblies were held in the month of December 1970. The Army was deployed all over the province of East Pakistan to help civilian authorities in the holding of peaceful election. A platoon of thirty soldiers was deployed in the north-eastern area of Jamalpur sub-division, in Sherpur Thana. I was the platoon commander, just over 21 years of age. I and and all the other young soldiers mixed very easily with the local youths. On the one hand we had to maintain a posture of seriousness about maintaining law and order so that election could be held freely and fairly. On the other hand, we went all out to know the feelings of, and boost, the nationalistic spirit of the people. The election was held as scheduled, and the Awami League won a super-landslide victory, and people were eagerly waiting for the party to form a government and frame a new constitution for Pakistan. The inaugural meeting of the national assembly was knocking at the door. However, the dawn of hope for the Bengalis was a false dawn. We belonged to the army. And if we could read the pulse of the people, surely our colleagues or seniors could also read the same. But the interpretation could be different. The eyes of the Panjabi (that is to say Pakistanis) would most likely read differently than the eyes of a Bengali. Indeed, that was what happened.

The Pakistani military high command in Dhaka thought that the battalions of the Bengal Regiment might emotionally tilt towards the Bengali population. These battalions consisted of about fifty percent Bengali officers and about ninety percent of Bengali troops. In the opinion of the Pakistani high command, these battalions were potential volcanoes, which could erupt, ignited by a very volatile political environment. Thus, the Pakistani leadership in Dhaka decided to split the battalions into various acceptable groups and deploy them to the countryside on some plausible excuse. The Second Bengal was deployed in its own operational area, that is, the district of Mymensingh and Tangail. The high command publicised that, in a politically unstable time, neighboring Thus, the military must be prepared to meet the threat. But as I have explained, the aim was to disperse the battalions so that it was no longer in a position to take collective decisions, thus reducing its effectiveness. But alas, the Pakistanis misjudged the situation entirely.

The first day of March brought the first shock. President Yahya Khan announced that the newly elected national assembly of Pakistan, which was schedule to meet for its inaugural session in Dhaka on the 3rd of March, would not meet -- the date was postponed. The people of East Pakistan burst into protest. On the March 2, the student leaders of Dhaka University hoisted the newly designed flag of an independent Bangladesh atop the Arts Faculty Building of Dhaka University. On the March 3, the student leaders on their own read out the proclamation of independence of a new country called Bangladesh. One day in the first week of March, Lieutenant General Sahibzada Yaqoob Khan (Commander, Eastern Command of Pakistan Army), addressed his farewell Darbar with Second Bengal. His short talk was very meaningful. The soldiers of Bengal Regiment were following the events closely. But since there were many Bengali officers in the battalions, the soldiers did not have to look beyond their own officers. They had confidence in the Bengali officers of their respective battalions. So was the case with Second Bengal. The soldiers of this battalion were spread all over, in the district of Mymensingh and Tangail, in their permanent location in Joydevpur, in Ordnance Factory Gazipur located five miles away from Joydevpur, and in the Ammunition Depot at Rajendrapur, eight miles from Joydevpur. The local people in all these locations interacted freely with the Bengali troops, thus bolstering each other's morale. The entire nation heard the speech of Bangabandhu delivered on March 7. The speech conveyed a lot. We in Second Bengal were no different from the other Bengalis. Our CO and second in command were Bengalis, and we had eight more Bengali officers in the battalion. Joydevpur in those days was the hub of political activism. Trade unionism was ripe in the surrounding areas. There was a big ground in Joydevpur, where political meeting could be held. Thus, the civilian and the military were more or less on the same frequency. The Second Bengal, being alone at Joydevpur, away from Dhaka Cantonment, had great freedom in planning its own activities. Let me jump back a few days.

Our battalion was equipped with obsolescent weapons. The Pakistani high command, in order to enhance the battalion's effectiveness, issued a fresh set of weapons to the battalion before January of 1971. Those were Chinese semi-automatic 7.62 mm caliber weapons. In a way, Second Bengal had two sets of weapons for one set of soldiers. In early March of 1971, the Pakistani high command in Dhaka ordered Second Bengal to deposit the old set of weapons. The battalion made efforts to deposit the extra weapons to the ordnance depot in Dhaka Cantonment which was 21 miles away, but could not do so because of continuous political turmoil which used to disrupt road communication. Thus, the battalion continued to hold nearly double the quantity of authorised weapons. A time came when the seniors of the battalion thought, “why should we deposit these weapons; these could be of use in the very near future.”The Second Bengal was part of 57 Infantry Brigade which was a part of 14 Infantry Division, both located in Dhaka Cantonment. The Brigade was commanded by Brigadier Jahanzeb Arbab.

That Second Bengal was holding on to extra weapons which was a matter of serious headache for the Pakistani higher military command in Dhaka. So, Brigadier Arbab decided to recover the extra weapons in possession of Second Bengal. He sent a message to the CO that he would come to say 'hello' to the battalion since the battalion must be feeling “lonely in a politically hostile environment.”He wanted to come and express 'military-solidarity' with the troops of Second Bengal at Joydevpur. He fixed March 19, 1971 for that. Little could the Brigadier imagine that he was helping Second Bengal write new pages of history, he was giving the opportunity to the people of Joydevpur to express their anger and condemnation of the government's policies.

The prevailing psyche and sensitivity of the locals need explanation. The people of Joydevpur, through various means reliable to them, had come to know of the impending visit of the Brigadier. They also learned or assumed with reasonable logic that the Brigadier was coming to snatch away the weapons from Second Bengal. The emotions of the people ran very high; they resolved not to allow the Brigadier to do so. The Brigadier came, accompanied by a team of seventy or so officers and soldiers. It was an imbalanced team. There were too many officers in the team than should have been, too many light machine guns and automatic weapons than the organisational rules permitted. None had any doubt that the Brigadier came with a camouflaged intention, that is, disarm Second Bengal. However, the Brigadier and the team misread the ability of the officers of Second Bengal to decipher his actual intention. The officers of Second Bengal stood in full battle readiness to welcome the team. Brigadier Jahanzeb Arbab was amazed and taken by surprise. He decided to make an honorable withdrawal to Dhaka. It was then that trouble for him began, indeed the trouble for Pakistan began; the first page of battle history of 1971 was being written.

There is a railway crossing at Joydevpur. The military installation was on the eastern side of the level crossing.

On the western side were the Joydevpur market and the built-up area. Thousands of local people under the leadership of local political leaders like Kazi Azimuddin, A.K.M. Mozammel, Nazrul Islam Khan and Abdul Mottaleb Chowdhury, had thronged the bazaar. They fixed two spots to empty railway wagons on the level crossing to effectively block the communication. The Pakistani Army contingent under Brigadier Arbab could not cross the level crossing because of the barricade. They tried to disperse the crowd, but failed. The Brigadier then ordered Second Bengal to clear the barricade and the roadblock and facilitate the honorable withdrawal of the contingent to Dhaka, with the order to the contingent of the battalion to shoot to kill if needed; the road had to be cleared by any means. The battalion raised its voice of protest. They refused to kill people. The Brigadier threatened them with severe punishment for what he termed as mutiny or at least, disobedience of command. Second Bengal agreed to take the punishment. Local people in thousands, who had thronged the bazaar, were aflame in their emotions and ready to start a skirmish. It was an uphill task to contain popular emotion. The mob fired at Second Bengal and at the Pakistani troops. However, the senior officers of regiment who were on ground, close to the site, used patience and tact to pacify the angry crowd. The roadblock was cleared with the help of the people. The Arbab contingent started their way back towards Dhaka, registering the disconcerting fact for the Pakistanis the Bengalis and the Bengali troops had revolted. The news of the revolt spread like wildfire. 26th March appeared to be too late incoming.

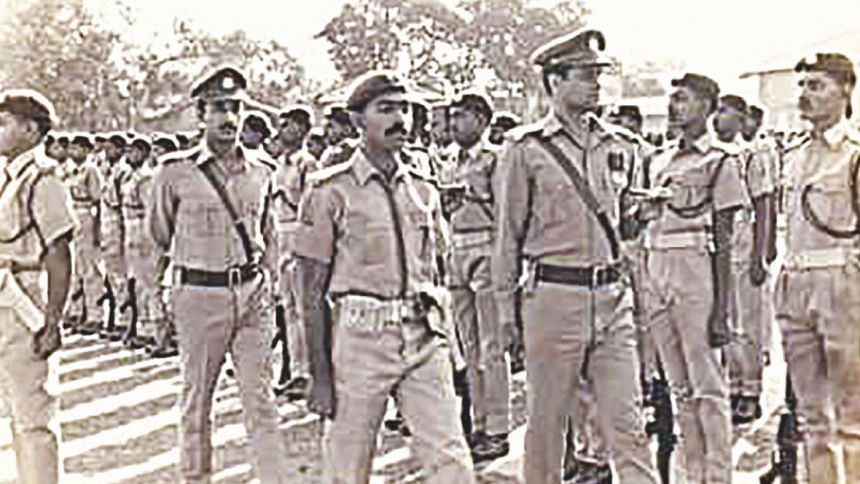

The CO of Second Bengal on that historic day, the 19th of March 1971, was Lieutenant Colonel Masoudul Hossain Khan; the Second in command was Major K.M. Safiullah. Major Moinul Hossain Chowdhury commanded the contingent which was ordered to confront the crowd with fire. Captain A.S.M. Nasim, Captain Mohammad Azizur Rahman, Captain Ejaz Ahmed Chowdhury performed other duties. Second Lieutenant Ibrahim, being the IO, hung around the CO, Colonel Masoud. Three days later, the CO was removed from command and placed under virtual house arrest in his house in Dhaka Cantonment, and Major K.M. Saifullah took care of the battalion for a day or two. One Lieutenant Colonel MA Rakib was placed in command or unit. The Commandant of the East Bengal Regimental Center, Brigadier MR Majumder, came in person to pacify the troops and make it easy for Colonel Rakib to settle down. Col Rakib, however, hardly had time to familiarise with the battalion, because events moved too fast.

I have not mentioned or discussed all that was happening in the-then provincial capital city of Dhaka between the President of Pakistan General Yahya Khan and leader of the people, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. But the events were creating an indelible impact on the minds of the Bengali people. Their sentiment and emotion had reached the zenith. We the soldiers were silent observers, apart from the events that I have described, our emotions were no different than the people's. The Pakistani military junta decided to use brute military force to solve the political problem. Following the day of 25th March 1971, at midnight, the crackdown began. 'Operation Search Light' was launched. Not only were civilian population and students attacked, unsuspecting young soldiers, sleeping unaware, were also attacked and killed in hundreds and thousands in many military barracks.

The Bengali officers and soldiers of the battalions of the East Bengal Regiment had made up their minds, but now they had to act on the decision – which was to revolt and join the war of liberation. They did it. The First and Third Bengal Regiments had to fight it out, taking a day or two. The remaining battalions did so instantly. In Chittagong Major Ziaur Rahman in Sholoshohor, Captain Rafiqul Islam in Halishohor, Captain Harun Ahmed Chowdhury in Kaptai, and Major Khaled Mosharraf with 4 Bengal, mutinied against the Pakistani higher command. Major Safiullah, with the elements of Second Bengal at Joydevpur and Gazipur revolted on the 26th. We took a day two organise our logistics to move out with everything that we had but nothing personal. We moved out to join our troops in Tangail and Mymensingh. Thus, ended the days of waiting and began the days of fighting.

The writer is a retired army officer.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments